Caitlin Cunningham’s solo show at sophiajacob, informally referred to as “Tan Penis Island,” is a carefully assembled collection of references around the subject of Tahiti and the insidious effects of Western hegemony, manifesting in a range of found ephemera and Cunningham’s own constructed pieces. The show is preceded by online promotion and explication of Cunningham’s choice of subject, and the assumption that viewers have some prior knowledge of Paul Gauguin’s work and the story of Mutiny on the Bounty – both of these cultural touch points provide the show with the backbone of it’s content.

The only direct reference to Gauguin by name is an austere white sophiajacob booklet printed to accompany the show, which quotes the painter’s obtuse intention to immerse himself in virgin nature and live primitively alongside the savages. In a contemporary progressive context, it’s easy to make him sound like an offensive buffoon, but Cunningham avoids casting Gauguin so directly. Rather, she skirts an ominous absence of exposé, providing select allusions relating to Tahiti as it’s seen through a lens of post-colonial Western culture, and exploring the interplay between fantasy and domination inherent in white European appropriation of foreign lands. In this exhibit, many of the most established, historicized appearances of Tahiti to be found in culture around us are taken out of context and laid in a tattered, suggestive cluster, mingled with potted plant garnishes and roughly crafted sculptures.

The latter objects are primarily used in the main feature of the show, “Be Mysterious,” a long low dais spread like a banquet or model table. Splashed in oozing red, yellow, and blue dyes, the items on the platform are laid out in a vaguely decorative arrangement, a farcical little jungle bisected by sickly fluorescent light fixtures resting amidst the other objects. The perplexingly crude brown sculptures appear to vary between pottery and body forms, evoking appendages, feces, and bloody entrails. The organic gesture of one plant’s leaves against the bulbs is an oddly sensitive sculptural moment amidst the rough mix of elements, which generally comes off as an intentionally bland and tongue-in-cheek at the expense of any sincere message built into the show. The insipid absurdity of the layout evokes unnatural treatment of organisms, and the allocation of visceral nature as decoration to be consumed.

In the back alcove of the gallery, the alluring light installation “The Greenhouse of Captain Bligh” takes the relationship between houseplants and artificial light even further than the centerpiece, and notably relies on Mutiny on the Bounty as a historical/literary reference. Cheaply erotic violet light and sloping wires hanging from the LED panels appear elegant and imperiously sensual over three dumpy, potted breadfruit tree saplings, a humorous contrast resulting in the malnutrition of the living plant resource for the sake of the artwork. In the Bounty vein, Captain Bligh’s “greenhouse” would have kept the breadfruit trees alive on the doomed voyage to the West Indies, as his crew grew more and more restless to return to their idyllic, erotic fantasy of life on Tahiti.

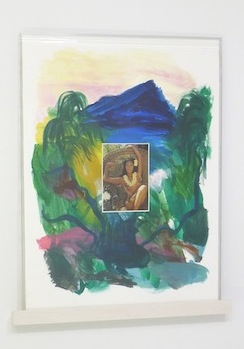

“Teva Sylvian” superimposes a postcard of a stereotypical exotic Tahitian fantasy woman over a small abstracted painting of a tropical landscape. The brush strokes and photographic image play against one another aesthetically and symbolically, the mass-producible print reducing the underwhelming painting to a background texture. In the shadow of Gauguin, the piece is one of the only direct critiques in the show, contrasting a likeness of the painter’s post-impressionistic style with a commodified depiction of his favorite subjects, topless Tahitian women. Nearby hangs the only concrete evidence of Western manipulation in Tahiti, a plain collage of several touristic postcards side-by-side with a book cover of a small volume on French nuclear testing in the island region. The distasteful and womanizing holidaymaking activities pictured and described in the pithy postcards are presented as the polite side of an ugly relationship between Western powers and French Polynesia, based on exploitation from vacation destinations to nuclear test sites.

For me, the weakest link in the show is the piece “Rainbow Warrior,” a blatantly simplistic painting on clear Plexiglas of a green ship with white sails, adorned with an amorphous white bird and a single rainbow pattern on it’s hull. Cunningham reveals in an interview at Daily Serving that the piece memorializes a Greenpeace ship, which was bombed by the French government in French Polynesia in 1985 (this date is smeared in red paint next to the ship). In spite of it’s vying relevance to the subject matter, the event seems like an impertinent historical reference in a show supposedly tied together around broad criticism of post-colonial oppression and exoticization, only serving to emphasize that violence still frames the politics of the region in modern times. Granted, the painting has piqued my curiosity to research more about Tahitian affairs, but it doesn’t make for an interesting artwork in and of itself. However, the inclusion of the Rainbow Warrior does provide a visual counterpoint to another manifestation of the Bounty across the room.

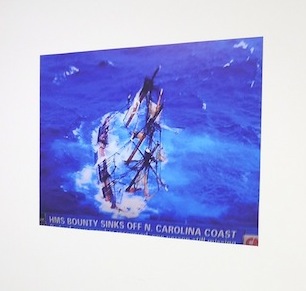

On the opposite wall is a large printed photograph of a Caribbean blue-saturated CNN newscast, paradoxically reporting on a sinking clipper ship, and labeled “HMS BOUNTY SINKS OFF OF N. CAROLINA COAST.” What the HMS Bounty is doing there is unclear in the piece (it was in fact a replica tall ship for the 1962 film adaptation of Mutiny), but the image demonstrates a fascinating contrast between technologies and storytelling of different eras. It’s a refreshingly up-front piece compared to the rest of the ambiguous installation, and anchors the other two ship-based works.

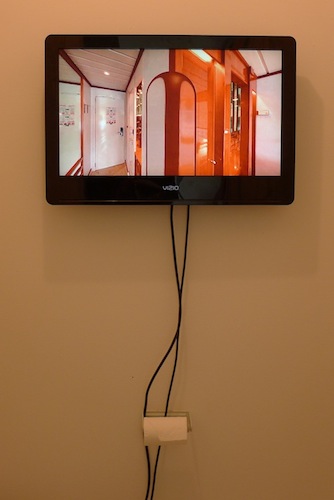

“M/s Paul Gauguin” is a long video piece consisting of several 360 virtual tours of different parts of a deserted cruise ship. A possibly phallic shaped lens form in the middle of the footage distorts everything the camera turns to. The placement of the screen in the bathroom brings up an interesting collusion of private/public space. The sanitized public toilet furnishes a bodily experience both personal and held in common with other visitors; similar to the way the cruise ship fosters self-centered vacation experiences to a mass of individuals at once. Though mesmerizing to watch, the lens effect in the video withholds some of Cunningham’s intentionality, remaining conceptually blank and difficult to relate to the rest of the show.

One of Cunningham’s choices, the implied transposition of the overhead gallery light to the “Be Mysterious” platform below, seems almost arbitrary in spite of it’s call and response logic. It’s unclear what she means by the incorporation of the gallery’s features with her own work, and whether or not she directly implicates the art space in the discussion.

The sparse interconnection of the pieces in this exhibit is a compelling accomplishment. Cunningham says a lot with only a small amount of loaded subject matter, avoiding prescribing the audience with her own opinions. Conversely, it distances the audience from Cunningham’s sharp critical voice, convoluting her reasoning behind specific choices. She subdues her strong feelings on the subject through intentionally oblique references juxtaposed with Gauguin’s colors and subject matter, leaving a fairly ambiguous vacuum of interpretation, demanding to the committed viewer. Without researching her references and reading her eloquent interview on the Daily Serving, there is a lot to assume about her thought process and the cultural violence she insinuates. The art pieces themselves are practically illustrations to a more brilliant thesis on post-colonialism from a Western feminist perspective. Though ironically, the work strains the audience’s ability to connect with a greater conversation, and not only invites questions about post-colonial chauvinist legacy, but raises doubts about Cunningham’s inexplicit choices themselves.

By her own account, nothing ties Cunningham personally with Tahiti. In her interview, she admits that she is more interested in identifying the “dismissive and domineering” authoritative voices that inform her own practice, and uses Tahiti as a metaphor to discern the twisted patriarchal culture to which she attributes those inner voices. In reanimating history of Tahiti’s appropriation, Cunningham herself engages in re-appropriation, albeit self-aware and critically disciplined. Exploitation it is a difficult subject to navigate, and while the majority of her cultural references to Western paradigms do not confront real and current Tahitian identity politics, the deliberately primitivistic pieces seem to simultaneously engage in exploitation and parody of exotic aesthetic stereotypes. This ambiguity seems intentional, but if meant as a conceptual complication of the art space, it’s a confusing one.

Out of the candid context of Cunningham’s exciting ideas, the show is able to maintain a strange reservation of insider political correctness by assuming no direct grasp or accusation of the post-colonial oppression churning beneath the surface subjects. Cunningham allows the looming issues to depart and supersede the show, invoking ethical disorientation without proposing any form of forward thinking (knee-jerk white guilt, anyone?). The exhibition is an intriguing presentation of historical and cultural narrative, evocative if essentially tangential from a bigger conversation that demands to be had beyond the gallery.

The show will be up for viewing at sophiajacob until Saturday, the 25th of May.

Author Mac Falby studies photography and humanities at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Class of 2014.