Wayne Koestenbaum at MICA by Kerr Houston

1. When he writes about the visual arts – and he has, relatively often, for more than twenty years now, in a range of other venues and on artists from Andy Warhol to Ryan Trecartin – he sometimes writes in brief numbered paragraphs. Impressions, you might call them, except he doesn’t quite trust that term. And when he speaks in public about his writing (as he did in MICA’s Lazarus Center auditorium, last Thursday, before a crowd of roughly a hundred), he is dapper, unimposingly charismatic, and thoughtful about the pacing of his content. Alternating between personal anecdotes and readings from several of his books (including My 1980s, a 2013 collection of essays), he offered a number of answers, both explicit and implicit, to the title of his talk: Why write about art?

2. Why write about art? There’s the money, of course; that’s true. But there is also, suggested Koestenbaum, a kind of discreet need for thoughtful commentary. “Art can’t speak for itself,” he proposed, “and it needs the foundation of a discourse, and I’m part of the factory that produces that discourse.” And then there are other more complicated reasons, as well. “I think of myself,” Koestenbaum said, “as a voyeur. I like to look; I really like to look.” Indeed, you might even say that some work invites us to look, and Koestenbaum willingly gives himself over: he speaks of surrender, and of transcendence. Which suggests, in turn, the possibility of an eros of writing. To wit: at one point in his lecture, while alluding to the writer Jean Genet, Koestenbaum developed a metaphor between masturbation and writing. Writing, according to such a logic, affords a sort of solitary pleasure, a self-indulgent release. It centers on the basic pleasure of ejaculation.

3. Factory, voyeur, masturbation: Koestenbaum’s affection for, and affinity with, Warhol seems clear. Like that artist, Koestenbaum is fascinated by elapsed time, by slowness and extension. Like Warhol, he returned again and again to the male body as a subject: to the boner, to jizz and to seed, and to the company of boys. (When he claimed, in speaking of Warhol’s films, that “Warhol’s pornographic impulse found a sacred home in art,” the alert listener may have wondered if he was also speaking of his own impulse, and career). At the same time, though, Koestenbaum sometimes also avoids (like Warhol) human contact. Writing affords a certain distance from the subject. He wants to be near the evidence of intense productivity. But he doesn’t necessarily need to meet the producer. The residue or the index can suffice. Art is a shrine in which we may study the offerings of others.

4. Warhol? Or perhaps Whitman – who went unmentioned at Thursday’s lecture, but who also anticipated many of Koestenbaum’s tendencies. Whitman, of course, composed masturbatory odes: after all, he sang the body electric. But he was also consumed by thoughts of others, and of their bodies. As Stephen Burt once wrote, Whitman, “more than any other American poet… did not feel complete in himself or satisfied with his writings unless he could take an interest in somebody else.” And so Whitman gingerly tended to the wounds of soldiers as a nurse during the Civil War – while Koestenbaum lay, a century later, on a stony beach on Long Island Sound with a man named Metro, who soon died of AIDS-related complications.

5. Warhol, Whitman: the influences quickly begin to multiply, promiscuously. Bruce Hainley once described Koestenbaum as “an impossible love child from a late-night, drunken three-way between Joan Didion, Roland Barthes, and Susan Sontag.” And maybe Frank O’Hara and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick assisted, in turn, in the delivery of that child. But surely Sontag, in any event, is the most important of these intellectual antecedents: in fact, Koestenbaum has referred to her as “my prose’s prime mover.” He, too, he is fascinated with the task of interpretation: on Thursday, he ventured that he feared that his writing might be seen as flimsily analytical, and extolled the value of what he labels over-interpretation. He, too, has written about photography and disease. And he recognizes aspects of himself in the assertion of Sontag’s Jean-Jacques (in The Benefactor, her first novel) that “I am a homosexual and a writer, both of whom are professionally self-regarding and self-esteeming creatures.”

6. Note Jean-Jacques’s use of the first person. That’s a form used frequently by Koestenbaum, in his prose and in his speech. (Indeed, he was invited to MICA in conjunction with a course on the use of the first person in contemporary writing). And art writing, Koestenbaum suggested, facilitates a certain honesty of tone. “Artists and art publications,” he told the crowd, “let me sound like myself.” What does that mean, precisely? In an answer to a question posed by a student, Koestenbaum acknowledged that the narrator, in his writings, is not necessarily the author who writes. He tries to efface, in his published prose, what he sees as a certain banality in his spoken language. The result, on the page, is a certain sprezzatura: a lightness of touch, characterized by a virtuosity that belies the difficulty of writing. Is that, then, himself? It is, Koestenbaum suggested, a self.

7. But the self is never completely free, of course, of external pressures and demands. Koestenbaum asserted at one point that the selection of essays in My 1980s offered “an argument for paying attention in the way that I like to pay attention.” But he also sees his practice as informed by a basic sense of obligation, or discipline. At night, he offered, he sometimes listens to an aria (he once wrote a book on opera) before falling asleep, and despairs at the impossibility of treating such a subject with an appropriate focus. “It is my burden,” he said, “to specify every nuance in that aria… I go to bed having failed to over-name. I am rebuked by the universe [for] having shirked the desire to over-name it.” Writing on the arts, then, is self-indulgent, and masturbatory – but it is characterized too by a sense of one’s impotence. Guilt always haunts the pleasure of the effort.

8. Is there something almost Catholic, then, in Koestenbaum’s approach to writing? It is at once confessional and riddled with a sense of its own insufficiency. It aims at ecstasy and revelation, and yet its author feels that it will never quite attain such an end. Flesh strives to become the word – and yet the word is still moored to the flesh. Such a characterization may seem forced – but listen, once again, to Koestenbaum. Thursday night, it turned out, marked the first time that he had been to Baltimore since 1981, when he left the fiction writing program at Johns Hopkins. That’s 33 years, he pointed out: Christ’s life, according to one tradition.

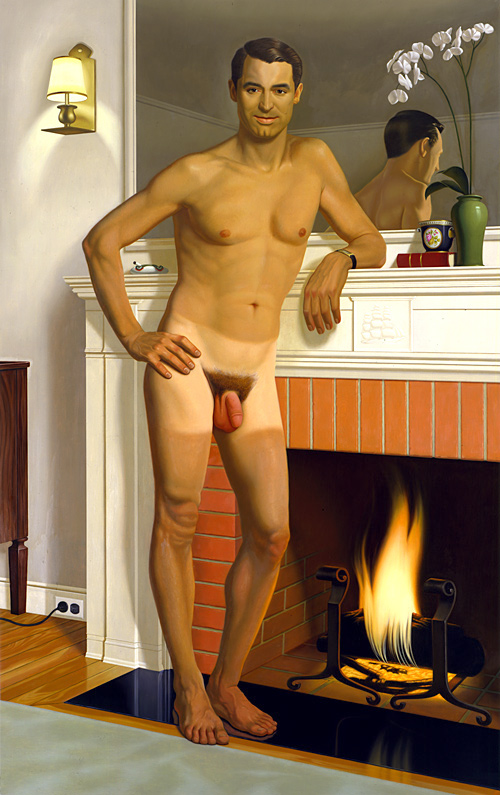

9. And so art, religion, and the body fold begin to collapse into each other, in Koestenbaum’s writing. There is not necessarily an overt ideological aspect to his work: there is no firm dogma, no attempt to stake out terrain that is resolutely Lacanian, or to refine the logic of Adorno. Instead, we get passages like this, in a 2005 essay on a painting by Kurt Kauper that depicted Cary Grant in the nude: “His legs resemble a Carpaccio hero’s, as if Cary Grant were Saint Sebastian or a courtier.” The logic is fluid, associative, and playful; the references are urbane and almost irreverent. And Koestenbaum’s eye is pricked, once again, by a prick: drawing on Roland Barthes’ famous notion of an affecting, piercing detail, he argues that “the punctum… is the room’s red lamp, approximately equal in size to the glans of Cary Grant’s penis.”

10. Why write about art, then? In a 1999 essay on James Schuyler, Koestenbaum tackled a similar question. “Why write art criticism?” he asked. “For love. Also, sometimes, for money.” It’s a glib, droll answer to his own question, but Koestenbaum’s own practice suggests ultimately, a richer range of reasons. Two years ago, in a conversation with Kenny Goldsmith, Koestenbaum contended that “I stage my sense of outlaw behavior within the proscenium of aesthetics, so my stances refer to laws that don’t exist anymore.” His work, he said, affords him both glee and abjection; in it, he can transcend historical and bodily limits. And perhaps, in the process, he can offer the reader something similar. Koestenbaum closed his 1999 piece on Schuyler by calling him “a major apostle of extraneous, minor pleasures.” Koestenbaum arguably belongs to the same clan.

Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.