Karen Fish Reviews New Arrivals: Late 20th Century Photographs from Russia & Belarus at the BMA

New Arrivals: Late 20th Century Photographs from Russia & Belarus, curated by Rena Hoisington, Curator of Prints, Drawings & Photographs at the Baltimore Museum of Art, contains only a small number of prints but the aesthetic pleasure to be mined here is expansive. The exhibition highlights fourteen photographers who worked in Russia, Belarus, Lithuania, and the Ukraine. All told there are twenty works, many from the 1980’s, that were collected personally by Brenda Edelson who served as the museum’s program director from 1973-85.

Boris Savelev’s Girl in a Box (1991)

Boris Savelev’s Girl in a Box (1991)

Another exhibition, Photo Manifesto: Contemporary Photography in the USSR, organized in Baltimore in the early 1990’s, made an impression on Edelson and was the impetus for her collection. That earlier exhibition showcased many of the photographers also seen here. In 2012, Edelson donated forty-seven of her photographs to the Baltimore Museum of Art. The work spans from 1959 to 2000, compelling years by any standard, artistically and/or politically, for the Eastern Block. In the 60’s and early 70’s, this region was off limits, closed behind the iron curtain. It is illuminating to see creative work that was produced during this time of tremendous societal and political change, work that was mostly hidden from Western audiences.

While the subject matter in New Arrivals is limited, it is not banal. The way the show has been hung invites one to consider an intimate view and brings the far-away close. The photographs are not large, but conventionally sized and draw one into a world that would have been unfamiliar to Americans at the time and the image of Lenin holds center stage. The Soviet Union only began to open to the West in the 1980’s, but there are small moments highlighted in a year, a country, and the mundane everyday that we recognize and empathize with.

Photography is all about showing a perspective, framing and isolating – putting a mat around something that the photographer wishes to bring to significance, a view that begs to be considered and seen separate from all the busy lack of structure the world generally offers. These photographs are a window into countries that were just beginning to open, and to what artists at that time were considering as their society was changing.

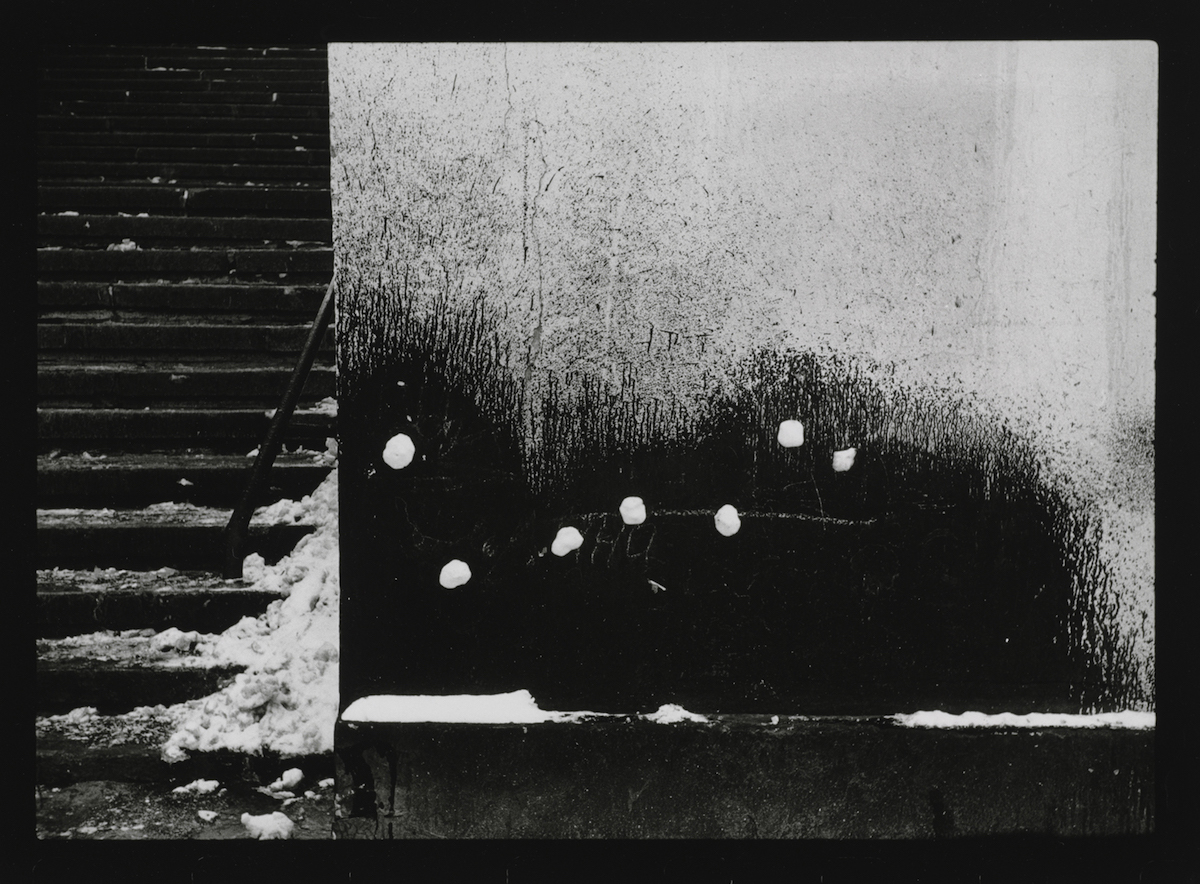

There are three prints by Alexander Slyusarev that bring to mind one of the American masters of photographic modernism, Minor White. White worked from 1937-76 and produced photographs of landscapes that made the viewer notice composition first, abstraction that was buried in the shapes of the ordinary world. White did this often by employing high contrast shadow and light, focusing on the strong compositional shapes the world offers up. It isn’t unusual to view a White photograph and first see an abstract composition only to notice the trees, snow, grasses, fence, and shadow upon further inspection. These techniques are also recognizable in Slyusarev’s work – creative innovations and techniques that both artists employed although separated chronologically and geographically.

Alexander Slyusarev’s Untitled(1980)

Alexander Slyusarev’s Untitled(1980)

Slyusarev’s snowy staircase beside a dark wall punctuated with snowballs has the same the strength of composition as White’s photographs. Additionally, there is a street scene that works a representation of pure shape and also reads as what it literally is – a kiosk among trees when one looks closely. The viewer “sees” or recognizes the abstraction first and then the actual forms become recognizable. In another photograph, a portrait of a man’s head in the foreground “beside” a distant smokestack reminds one just how powerful portraiture can be. The portrait makes us curious and at the same time shows us something we’ve never quite seen before but oddly recognize; the portrait captures essence. The power of a portrait is often derived from this recognition – we see something familiar in a stranger’s face and it catches us off guard. We are surprised by the connection.

There is a quiet group of photographs by Igor Savchenko from Belarus that spur curiosity precisely for the reason that there are no heads to be seen. They are investigations of gesture and anonymity. The sequence is titled “Alphabet of Gestures,” and consists of toned gelatin silver prints from the early 1990’s. These are photographs of photographs, called “counter-documentary” works. Savchenko might have appropriated found photographs, anonymous snapshots, or used old family photos. We don’t know and it doesn’t matter because the work investigates the anonymity of the past. The gestures here are emblematic. He re-photographed other photographer’s prints and zoomed in on the imagery of held hands, hand gestures, and poses.

In the process, we lose the context of the original photograph. Instead, these ambiguous images focus the viewer on something new: a gesture that bring his or her own context to the viewing. The series is quietly compelling in ways that are hard to identify. It calls to mind a found fragment, a partial view, intimacy, and importance without the usual “story.” They could be any of our distant relatives – the floral dress, the women’s figures in stripes, seated together with only the torso and lap viewable. In the purest sense, the photographs are a glimpse into that magical world the image can conjure. They render the past somehow graspable. We recognize the hands, the intimacy implied as our own, or those of lost relatives. Different fashions for sure, but the essential hand holding we all still do ourselves.

Finally, there are four photographs of a statue of Vladimir Lenin by Sergey Kozhemyakin. While the statue of Lenin is the focal point of each print, it is not the subject. Rather, the content of these prints is the way the photographer plays with the presentation of that very recognizable image. What is notable is the way in which the Lenin statue is simply a starting point, the image either scratched or darkened and finally rendered unrecognizable. This is about manipulation: symbolism for sure, but also it is “play,” creative thinking, using sequence to explore a sociological and political reality artistically.

Sergey Kozhemyakin’s Transformation of the Image (1990), one from series of four

Sergey Kozhemyakin’s Transformation of the Image (1990), one from series of four

Kozhemyakin’s photographs are more than powerful symbolism enacted through the artistic process. They are charged with the knowledge that these sorts of photographic manipulations would have been serious crimes in a previous time. They would have even been dangerous to produce and, much more so, to show before Western influence and broad openness swept the region. Standing before this work, one considers the ways in which state images, and other political historical images, have been creatively manipulated to indicate and invite the viewer (whether a Russian or a U.S. citizen) to consider all that has changed in the collective consciousness.

The photographs that Brenda Edelson collected arguably make our big world smaller and more intimate. Though similar to photographs American photographers were printing around the same time, the subject matter and perspective separate us as much as they draw us together. They enlarge the BMA’s photography holdings because as a collection they allow us a rare glimpse into a region that was previously off limits and secret.

This is a quiet little show, and the work insists that we look closely. In doing so, we remember how the visual image prompts consideration of presentation, subject matter, and translation of the human experience. This show proves that it is through art, vehicles of literature and visual work, that we come to know a region and a people that we previously hadn’t considered. Art, at it’s best, can translate all the intangibles that make the world so fabulously gritty and real. It isn’t difficult to imagine some of these photographs tucked away in our own shoebox of dusty prints, though we are decades and countries away.

New Arrivals: Late 20th-Century Photographs from Russia & Belarus is on exhibit at the Baltimore Museum of Art through March 20, 2016.

Top Photo Credit: Galina Moskaleva. Untitled. 1996. From the series “Children Who Have Had Thyroid Operations”. The Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Robert and Brenda Edelson, BMA 2012.512

<><><><><><><><><>

Author Karen Fish received a BFA in photography & painting from Arcadia University and did her graduate work at the Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University. She’s published two books of poems, The Cedar Canoe (University of Georgia) and What Is Beyond Us (Harper/Collins). Currently, she serves as the chair of the Writing department at Loyola University Maryland. Over the years her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, The American Poetry Review, The New Republic and Slate.