The Martin Puryear Retrospective at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

By Brendan L. Smith

For half a century, Martin Puryear has combined the tools of a gifted craftsman with the exacting eye of an artist, creating massive installations that emanate warmth and humility despite their colossal size.

In the first exhibition to combine his sketches, drawings, and maquettes with his sculpture, Martin Puryear: Multiple Dimensions at the Smithsonian American Art Museum reveals the evolution and recurring forms that led to a final expression in curving wood, chiseled stone, or cast bronze. Born and raised in D.C., the exhibition is a homecoming for the 75-year-old sculptor who now lives in upstate New York. He collaborated on the design of the exhibition organized by the Art Institute of Chicago that features more than 50 prints and drawings along with 14 sculptures, including some pieces that have never been shown publicly.

Puryear isn’t well-known to the public, but he ranks as one of the most important sculptors of the past century. As a master woodworker trained in building furniture, bows, and canoes, Puryear has spent an entire career combining utilitarian functions with elemental forms that often defy easy categorization. As a black artist, he doesn’t easily fit into any art movement or clique, and his work hasn’t followed any flashy trends, yet he has still garnered many accolades and public commissions across the world. Puryear often has been reluctant to explain his enigmatic artwork in too much detail because he wants the work to speak for itself.

“The work itself can have an identity that can hopefully speak, whether it’s through beauty or otherness or whatever quality you put into the work.” Puryear said in a PBS interview. “The work doesn’t have to be a transparent vehicle for you to say things about life today or what you see people doing to each other. I’m making a case for my own vision.”

The exhibition stretches back to the 1960s with drawings of thatched-roof huts and tribesmen from Puryear’s two-year stint as a Peace Corps volunteer in Sierra Leone. The huts appear again two decades later in a prepatory drawing showing three different huts with two intertwining strands weaving downward, rooting the huts to a simple wheel that creates a sense of both precariousness and balance. From left to right, the drawn huts shift from a realistic representation to a skeletal form of the hut’s frame and finally to a jellyfish-like shape with the bare outlines of the hut still visible.

“Bower“, 1980

“Bower“, 1980

The artist was still experimenting, fleshing out various designs, but he later changed gears because the hut disappears altogether in the final 1982 sculpture called “Sanctuary.” The hut is replaced by a stark, wooden machine-cut cube with the sharp, impersonal angles of an IKEA storage unit. But the cube is a vessel or home, a recurring theme in Puryear’s work, that offers a sanctuary rooted to the earth by bark-covered limbs of maple and cherry reaching toward the wheel below.

Another sketch not included in the exhibition offers some insight into the sculpture’s meaning and possible connection to a devastating fire in 1977 that obliterated his Brooklyn studio along with most of his sculptures. A handwritten note on the sketch states “a period of grieving followed by an incredible lightness or freedom,” illustrating how the indelible power of art can revive the creative mind and beating heart of an artist who has to start all over again.

“Vessel,” 1997-2002

“Vessel,” 1997-2002

A graphite drawing on paper from 1992 offers a window into the more technical nature of transforming a two-dimensional vision into a three-dimensional form. The drawing is squared with a grid for enlargement along with handwritten notes about dimensions and ratios. The final sculpture called “Vessel” fills an entire room with its precisely crafted, interlocking frame of Eastern white pine in the contours of a traditional water flask or wineskin with a short spout. A large black ampersand of tar-coated mesh fills the interior of the skeletal frame. The ampersand appeared in Roman cursive in the 1st century A.D. as a combination of the letters E and T for et, meaning and or plus. The work offers a question without an answer. And what? The vessel is imbued with a sense of anticipation of what is unknown but yet to come.

The exhibition also includes two very different maquettes or related sculptures for “Big Bling,” a massive yet temporary 40-foot sculpture installed last month in Madison Square Park in New York City. One maquette shows the sculpture’s precise wooden grid suggesting order and manmade structure that rises like a rollercoaster to a large gold-leafed shackle. An interior, elongated section of negative space offers a contrasting image of nature like a pool of water, reminiscent of 18th-century landscape designer William Kent’s famous quote that “nature abhors a straight line.” The large shackle at the sculpture’s peak resembles a ring for an oversized medallion, as the title implies large, gaudy jewelry clinking together with a tinny sound, or bling bling, in a physical representation of hip-hop slang and culture.

“Big Bling” Maquette, 2014

“Big Bling” Maquette, 2014

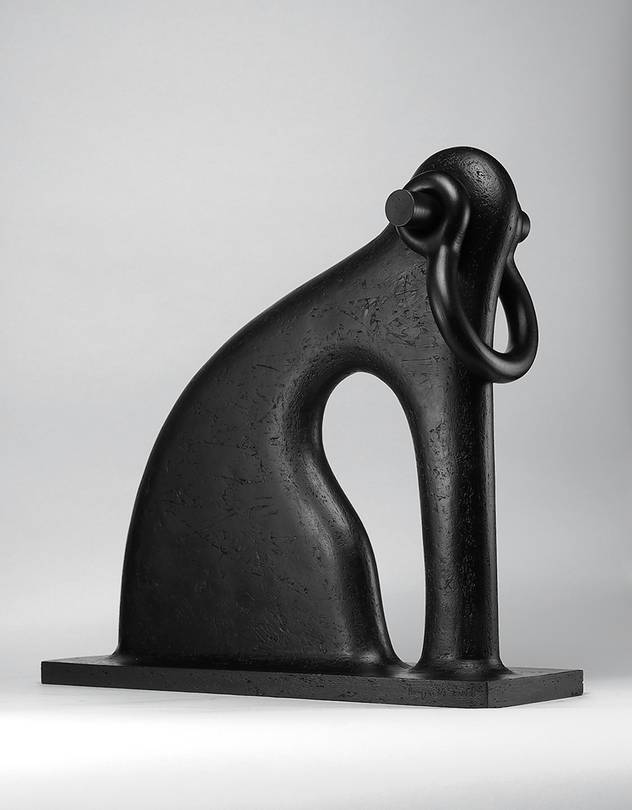

“Shackled,” 2014

“Shackled,” 2014

In “Shackled,” Puryear uses the same overarching form of “Big Bling,” but the foreboding heaviness of its solid black surface is cast from lead, the same material used in shackles that bound despondent slaves inside squalid ships sailing to America, leaving their families and ancestral homeland behind. It’s one of a few sculptures by Puryear with a clear social commentary, and its combination with “Bling” offers historical context for the plight and resurrection of the black experience in America. Puryear presents the shackle as a brutal symbol of confinement that morphs into the whimsical world of “Bling,” the boastful swagger and ostentatious display of wealth that also conveys a real sense of personal freedom and collective black pride.

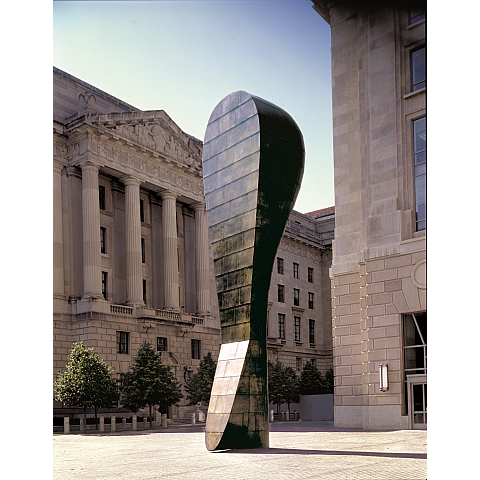

The exhibition also includes some sketches for “Bearing Witness,” a colossal 40-foot-tall sculpture located just a short walk away in Federal Triangle plaza in downtown D.C. Installed in 1997, the sculpture rises to towering heights in the seat of political power at the epicenter of bitter partisan battles and massive public protests that challenge the government’s sins and willful failures to act. Created from hammer-formed bronze plates welded to a stainless-steel armature, the sculpture resembles an exclamation point sliced in half while the title implies a watchful eye.

“Bearing Witness,” 1997

“Bearing Witness,” 1997

In a previous interview, Puryear said the sculpture is “directed toward people rather than toward the government” because “the people talk back to the government” in a democracy. But the people also bear a responsibility both as witness and active participant in deciding their own fate and the direction of their country. True to form, Puryear offered a glimpse into his insights but backs away from saying too much so the work can speak for itself based on the interpretations of the viewer.

“A true democracy requires that the governed be enlightened, vigilant, and vocal,” he said. “Most people see a giant head, but the form is abstract and not based on any one set of associations.”

Martin Puryear: Multiple Dimensions will be on display until September 5, 2016 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum at 8th and F Streets NW.

Author Brendan L. Smith is a freelance journalist, mixed-media artist, and father of two rambunctious boys in Washington, D.C.

“Maquette for Bearing Witness,” pine, 59 3/4 x 15 x 19 1/4 inches, 1994

“Maquette for Bearing Witness,” pine, 59 3/4 x 15 x 19 1/4 inches, 1994

“Big Bling” installed in NYC

“Big Bling” installed in NYC