The History and Reality of Warfare through the filter of Broomberg and Chanarin at the BMA

by Cara Ober

When offering social critique, you have three options. You can go full tilt Cassandra, using emotional soapboxing to spread well deserved admonishments, fear, and guilt. You can be a formalist, and present your critique abstractly, with scientific observation and statistical analysis. Or, you can be the funny guy who speaks the inconvenient truth to power while cracking everyone up.

In the BMA’s Contemporary Wing, Adam Broomberg (England) and Oliver Chanarin (South Africa) take on the dark and messy topic of war using two of these approaches with mixed results. This exhibit curated by Ann Shafer presents the collaborative duo, who first achieved worldwide fame through their design and curation of Benetton’s publication Colors, and offers disparate bodies of work, which alternately lampoon and venerate the accoutrements and approaches to warfare, confusing our approach to the subject matter and to their work as a whole.

Although snippets of bombastic, often ridiculous, sound waft into the gallery from the nearby black box theater, humor is not an obvious first reaction to the three series of wall works on display. Each comes off as a formal study, subdued by a black and white palette and lean formal restrictions.

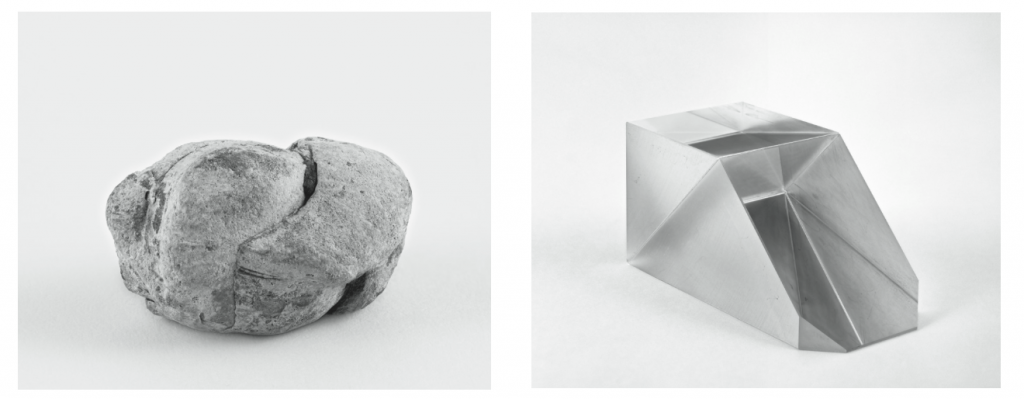

Four giant photos, each depicting one highly detailed object on a white background, dominate the central wall of the gallery. Two appear to be large boulders while two resemble metal birdhouses. Printed close to 8 feet long, these monumental still lives reveal rich, sharp surface detail and maintain their tight focus even just inches away. Wall text reveals the two rocks, pockmarked and richly detailed with lichens, are actually fused bullets from the American Civil War. Only twenty or so exist, and these tiny objects are rare collectibles for war history buffs and aficionados.

For Broomberg and Chanarin, the fused bullets represent a freak occurrence; a breakdown in the usual operations of war that saved two lives, at least momentarily. The objects also represent a time when war was conducted up close and personal, when soldiers were instructed not to shoot until they could see the whites of their enemy’s eyes; a time when rules of engagement were enforced by drums and gentlemanly conduct was viewed as sport by nearby spectators.

The second two images depict glass prisms, viewing devices designed to lengthen the killing range between soldiers on opposite sides. Used in World War Two, the objects dramatically changed the rules of war, with the ability to hit targets much farther away. Presented in a historical timeline from left to right, the fused bullets represent an ideal romanticism of war, while the prisms, although antiquated, illustrate the impact of technology on war and offer the question: Just because we have the technology, is it ethical to use it?

If you move right in the gallery, the historical timeline continues to a series of small black metal plates that look like 4×5 negatives, mounted to the wall by gold hardware. If you tilt your head sideways, you will notice delicate lines forming modernist compositions or diagrams for arcane team sports. Each is a direct copy of an original image, smoked black and waxed, with the drawing incised into the ephemeral surface. During World War Two, the originals functioned as diagrams for higher tech prisms than the ones depicted in the nearby photos, which were made in a factory outside Dresden. Ironically, the devices made it easier for Germans to hit their targets from airplanes, including the tragic fate of the city of Dresden, which was burned to the ground for no other reason than to test military might.

Although subtle, these fugitive images (displayed under Plexiglas boxes because a swipe of the finger could sweep them away) reinforce the compartmentalized way technology changes the impact of war. Their delicacy lies in direct opposition to their actual purpose, and this irony does begin to elicit the beginning of a wry grimace.

Moving right, a third series of small photos depicts squished white pillows in the rich gray tones of traditional black and white photography. Each is arranged deliberately in a smooshed vertical composition, where cylindrical balloons, pillows, and rounded humps seem to arrange themselves. Only very close looking reveals that there is a human figure under the shapes, that she is wearing the traditional white bulbous costume of the French bouffon, the ridiculous comedian allowed to mock the king once a year. Each image is named and numbered corresponding to Francisco de Goya’s print series Los Disparates (The Follies) 1815-1823, a loosely grouped series of dark and dreamlike images that explore Spanish proverbs and political issues. In addition, wall text mentions that they were also inspired by Hans Bellmer’s 1934 photographs of dismembered doll sculptures.

To really appreciate the ideas embedded in the series, the audience must read the wall text and look up the Goya series. I’m not suggesting that the audience is anti-rigor or research, or that they should be, but I would like to point out that these three series, viewed together, present opaque messages that are entirely missable if you choose to interact with the works directly.

Next to the photos, there’s a glass case full of white lumpy miniatures. From a distance, the case appears to be full of large popcorn kernels but there are ceramic faces underneath the clay. Each is a tiny tchotchke, a drummer boy transformed into a traditional French bouffon, his drum creating a distended hump or gut, rendering him oddly disfigured. As a group, they make a tiny army of pathetic, yet cheerful soldiers, a subverted representation of the children whose drumbeats signaled the choreography of war before technology replaced them.

With the introduction of this body of work, suddenly one becomes aware of the connections between the other series in the room, especially between the bouffon and historic warfare. The audience is finally connected to the reality and contrast between methods of modern and historical warfare. This is a welcome change that only occurs when Broomberg and Chanarin explicitly embrace their role as bouffons, rather than scientists or researchers, in exploring their topic.

In this piece, a tiny army of ridiculous sculptures employs overt humor in their message, and as such, there’s warmth and energy, a familiarity and nostalgia that draws one in to their narrative. Although you cannot tell that they are drummer boy figures without help from wall text, their simultaneous familiarity and strangeness makes them compelling. Their proliferation and arrangement physically reflects the ideas they represent – both the tragedy that children continue to be involved in war and that celebrating the past, more gentlemanly, rules of warfare is futile.

Although the three bodies of formal 2D works are visually arresting, offering cohesion and variety, and confidently fill the gallery in an aesthetically satisfying way, they are dependent upon wall text in communicating effectively about warfare. For visitors too impatient to read explanations, this exhibit will function as a successful visual experience, but they will absorb none of B&C’s pointed critique. It’s only when they employ a wicked and ridiculous humor, which is hinted at in their tiny sculpture army, and fully realized in their accompanying video, “Rudiments,” that their deep, complex, and humanly empathetic messages can be heard.

If you follow the sound of military drumbeats and marching band, you will leave the Front Room Gallery and find yourself in the BMA’s small black box theater. “Rudiments,” a 12-minute pseudo-documentary with an animated musical score by Kid Millions, plays on repeating loop. You’ll do well to take a seat on one of the benches provided and let the close-ups of awkward teenaged faces, complete with pimples and resigned boredom, march to the syncopated beats of the engaging musical score. As you watch the teenagers in ill-fitting military and marching band style uniforms attempt to march in line, it’s unclear whether the filmmakers are silent observers or choreographers.

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin: Rudiments (2015) from Forma Arts on Vimeo.

There’s a “Zelig” or “Sleeper” feeling in this short film, where slapstick comedy comes from direct observation of the inanity of real life, but the vulnerable humanity of each individual is captured and honored. As the musical score switches from oompah to jazz percussion, the film clips to sessions where B&C’s favorite bouffon (the same model from the photos), played by Hannah Ringham, instructs the young soldiers on a classic slapstick move – falling down dead. As the snare drum beats, teenaged soldiers practice falling, pantomiming their own deaths. Although we’re seeing kids acting like kids, the military uniform and environment provides a context that is truly disturbing. Suddenly, the silly drummer boy sculptures encased in white become tragic.

The film segues to Hannah the bouffon, in her bulbous white costume, making lewd and silly faces, posing for the camera. Her face is strange and expressive; she comes off like a cartoon and successfully embodies the proverbial naughty imp who mocks authority and order.

In the final scene, her persona changes completely, catching the audience off guard by raw and authentic emotion juxtaposed with sound and footage of one of the young soldiers singing a mournful version of Ella Henderson’s “Yours” in Karaoke. If you are a sympathy crier, bring some tissues. This transition is oddly, effectively moving. A sweeping wave of empathy, sadness, and frustration, coupled with the innocent voice and song, will shock you.

Like the other works in the exhibit, the film’s construction is meticulous (except for a weird soda bottle in the background of a few of scenes), but its ability to communicate abstractly and explicitly using physical humor forges a direct connection with the viewer. If possible, when you visit the BMA, watch the video first, before experiencing the rest of the exhibition. Although the contrast between video and 2D works are abrupt, the film softens and humanizes the more abstract and formal works.

When dealing with an unwieldy and polarizing topic such as war, an artist must have a system or tool for creating distance and perspective, if they wish to meaningfully connect with audience. In a similar exhibit at Lisson Gallery in London, Broomberg and Chanarin were able to include “Double Act,” described as “a live performance with two drummers, one snare drum, one chair, two clocks and a lead carpet, in which the drummers play a drum roll for the duration of the exhibition, without interruption.”

Imagine the pristine and formal works at the BMA now, with two drummers playing in the gallery. Imagine how much humor, absurdity, and discord this performance would have added to the exhibit. Without obvious and serious bouffon-ery, the type that makes you seriously confused and uncomfortable, the works at the Baltimore museum maintain their elegance and power, but the humor is mostly lost until you watch the film. Without a performance to contradict and animate their 2D works, the audience misses an opportunity to engage as deeply through humor as Broomberg and Chanarin intended.

*****

Front Room: Broomberg and Chanarin will be on exhibit at the BMA through September 11, 2016.

Author Cara Ober is Founding Editor at BmoreArt.