Judy Chicago’s newest body of work gapes at catastrophe. In The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts through Jan. 20, 2020, the artist takes a close, hard look at grief, mortality, and the extinction of animals through a series of small, diary-like paintings on white porcelain and black glass. The images are direct, more diagnostic than poetic, and suffused with raw grief—the artist said that after finishing the work, she had to take a year-long break to recuperate. It’s a respectable task: directly confronting death and all of its unknowable unknowns, while also depicting the effects of human-wrought destruction of Earth; in other words, those deeply disturbing realities running through our minds a lot lately. Why did I walk away from this exhibition with an unsettling ambivalence?

I have not yet seen, in person, the work for which Chicago is best known, but at the mention of her name in any text, the canonical and multifaceted The Dinner Party (1974–79) must also be referenced. In this piece, which is permanently installed at the Brooklyn Museum, a massive, triangular banquet table with embroidered and ceramic place settings reminiscent of vulvas and butterflies honors 39 mythical and historical women, and encloses a central tile floor inscribed with the names of 999 more women. The 1,038 named women were selected by Chicago and assistants based on criteria determining whether the woman significantly contributed to society, tried to make the world better for women, or lived/worked toward a more egalitarian society. The Dinner Party was an attempt at centering women of Western civilization who throughout history were marginalized, their work in the arts, science, medicine, activism and so on significantly harder to locate than that of their male counterparts. This work’s flaws and omissions—namely, its predominant whiteness (which Hortense Spillers and Alice Walker critiqued separately in the 1970s and ’80s), and its implicit equation of womanhood with female genitalia—expose obvious gaps and biases not only in Western archival sources, but also within our understandings of gender and feminism, then and now. Regarding ostensible oversights in the work, the artist has responded that she and her assistants were doing all this research that had not been done before, culling together information about a thousand women sidelined by history. (Before the internet, at that.)

All of this cements The Dinner Party as a critically complicated feminist artwork, especially with the additional layer of the public’s various readings (from dully sexist to righteously critical), which ultimately revealed even further the deep entrenchment of systemic oppression. And just as The Dinner Party became arguably even more complex upon its entry into the world, so does The End, uncovering an uncomfortable stupefaction in the face of death and climate doom.

Divided into three distinct sections—the stages of grief, the artist’s visions of her own death, and the brutality humans have wrought upon animals out of greed, capital, and cruelty—the exhibition of The End sets up a psychological journey, starting with a framework for understanding grief and our own impermanence. “If you can allow yourself to overcome the level of denial we practice in our culture, start thinking about your own death and thinking about mortality, it will help open you to think about the choice we have on the death we’re inflicting on others,” Chicago said at a September talk at the NMWA.

Judy Chicago, “Stages of Dying 5/6: Depression,” from The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, China paint on porcelain (2015)

The first section, “Stages of Dying,” draws upon psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ ubiquitous theory of the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Chicago depicts each of these stages using a bald-headed female body, often in a funny-but-not and rather unambiguous manner, painted on small, white porcelain plaques. “Anger” shows the figure gritting her teeth, arms raised with closed fists, and outlined in a meaty, red aura; “Denial” has her on hands and knees, willfully plunging her head into the sand and turning her whole body into a landscape. The soft rendering takes it all to an absurd level of sick whimsy, which somehow makes me like “Denial” the best. In “Depression,” meanwhile, her pale-skinned body, oddly both anemic and flushed, is doubled and also doubled over in grief, heads in hands, perhaps signaling a kind of dissociation from the self that can occur in extreme depressive episodes.

This pre-death reckoning anticipates the “Mortality” section which includes Chicago’s “How Will I Die?” series, all kiln-fired glass paint on sheets of black glass and one bronze sculpture. Chicago, who celebrated her 80th birthday this year, plunges into the personal more deeply here, confronting her own eventual death and perhaps how she’d like to go. In their unique and specific subjectivity—the artist’s interiority illustrated and accompanied by her own handwriting on each glass sheet—these small paintings stand out. Chicago’s anxious admissions and questions threading through the painted scenes are also attempts toward some grand universality: In one, the text “Everyone hopes to die peacefully” floats over a seemingly dead woman’s body lying bare atop a lustrous, oil-slick-like platform. In another, the phrase “No one wants to die hooked up to machines in a hospital” reads like a banner over the medical devices plugged into a body lying prostrate on the cell-like bed. The former image is a peaceful, classical fantasy; the latter is closer to most people’s reality.

Judy Chicago, “How Will I Die? #9,” Kiln-fired glass paint, Liquid Bright, and oil paint on black glass (2015)

In “My/Mother’s Body” a woman stands before a mirror, giving the illusion of a side-by-side diagram of the front and back of her body. She appears to be assessing the wrinkles and sags that mark her flesh, the scene captioned with a quote from Simone de Beauvoir about her mother’s death: “The sight of my mother’s nakedness jarred me… I was astonished at my own distress.”

This composition opens the scene up for the viewer’s investigation of the aged body, often unseen in Western culture. The philosopher Martha Nussbaum, Chicago’s co-panelist in September, has written about disgust directed toward the human body, particularly as it ages. At the NMWA talk, Nussbaum wondered what happened to feminists of the second wave who made it to this age, and who can’t seem to grapple with bodily changes. Back in the day, she said, “We were reading Our Bodies, Ourselves and we were saying: Female bodies were objects of disgust for others—we’re not going to allow that to happen to us. We’re going to look at our bodies. We’re going to get to know our bodies. We’re going to love our bodies… Now, as we’re aging, what’s happened to that goal, that love of ourselves?”

I would guess that our fast-paced, image-obsessed and narcissistic culture has played a big role there—despite increasing collective awareness of this dynamic, it still takes a concerted effort to shrug off that certain young, “flawless,” white, feminine ideal constantly projected at us in all kinds of media. This, along with our enculturated disgust/fear of our own and each other’s bodies, turns us inward and makes our world feel so much smaller than it is.

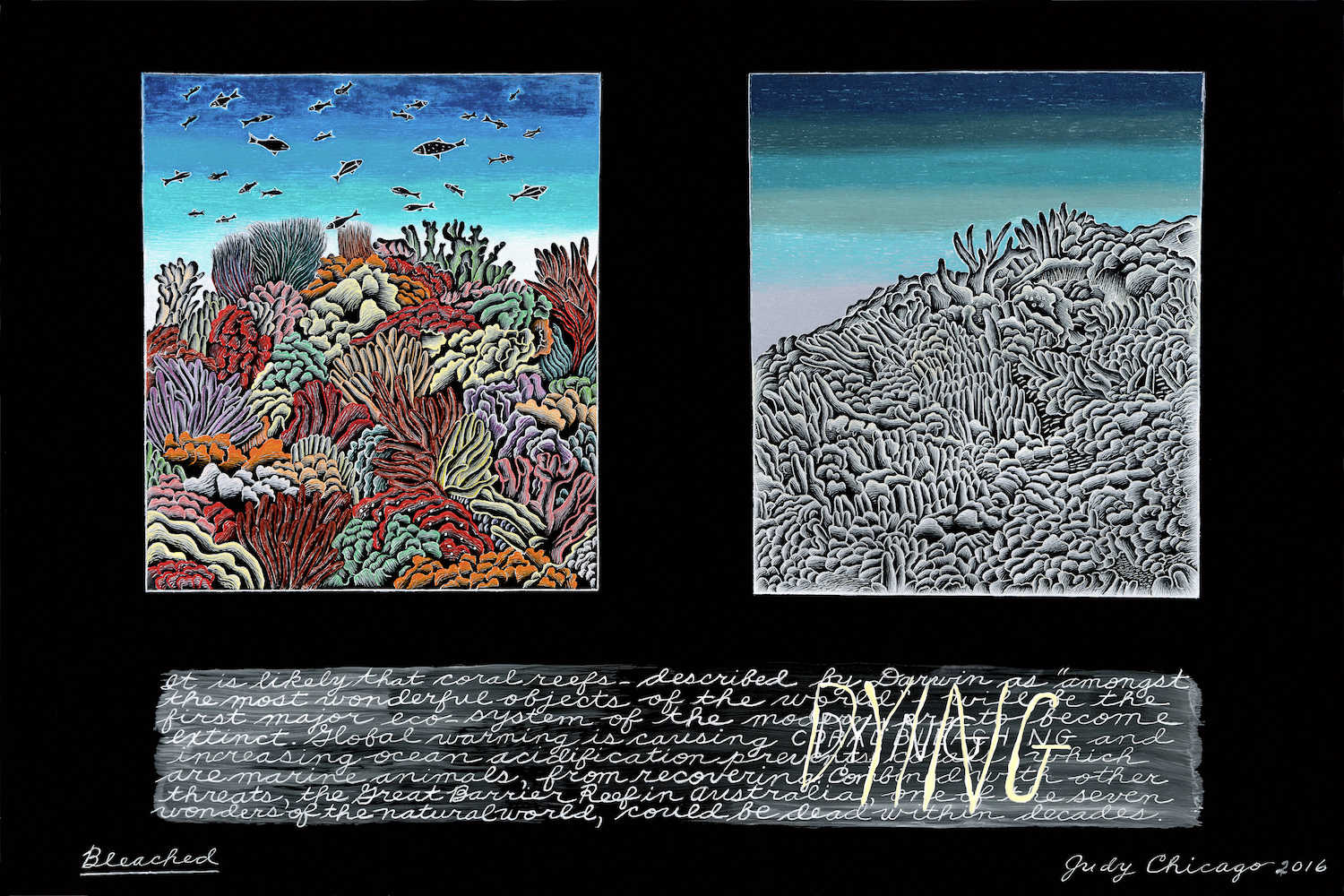

But I digress—it’s easy to do here, especially when the shiny black mirror-like backgrounds of Chicago’s work literally bring you into the scene. Which takes me to The End’s third section, “Extinction,” which in one sense pulls us out of ourselves and our inner wondering, but then places us back into the horrific state of our planet—and, subtly, our own complacency amid disaster. The global temperature continues to rise at an alarming rate, and if nothing changes basically immediately, it will be too hot to go outside in many places. People are already feeling these effects, but in this series, Chicago draws our attention to the animals. In “Stranded,” a polar bear clings to an ice floe in a cold, choppy sea under a black sky. In the text on this panel, with a certain self-awareness, the artist notes that this particular lonely image has turned into “a symbol for climate change and the exploitation of the environment which is now greater than nature can withstand.”

Judy Chicago, “Stranded,” kiln-fired glass paint on black glass (2016)

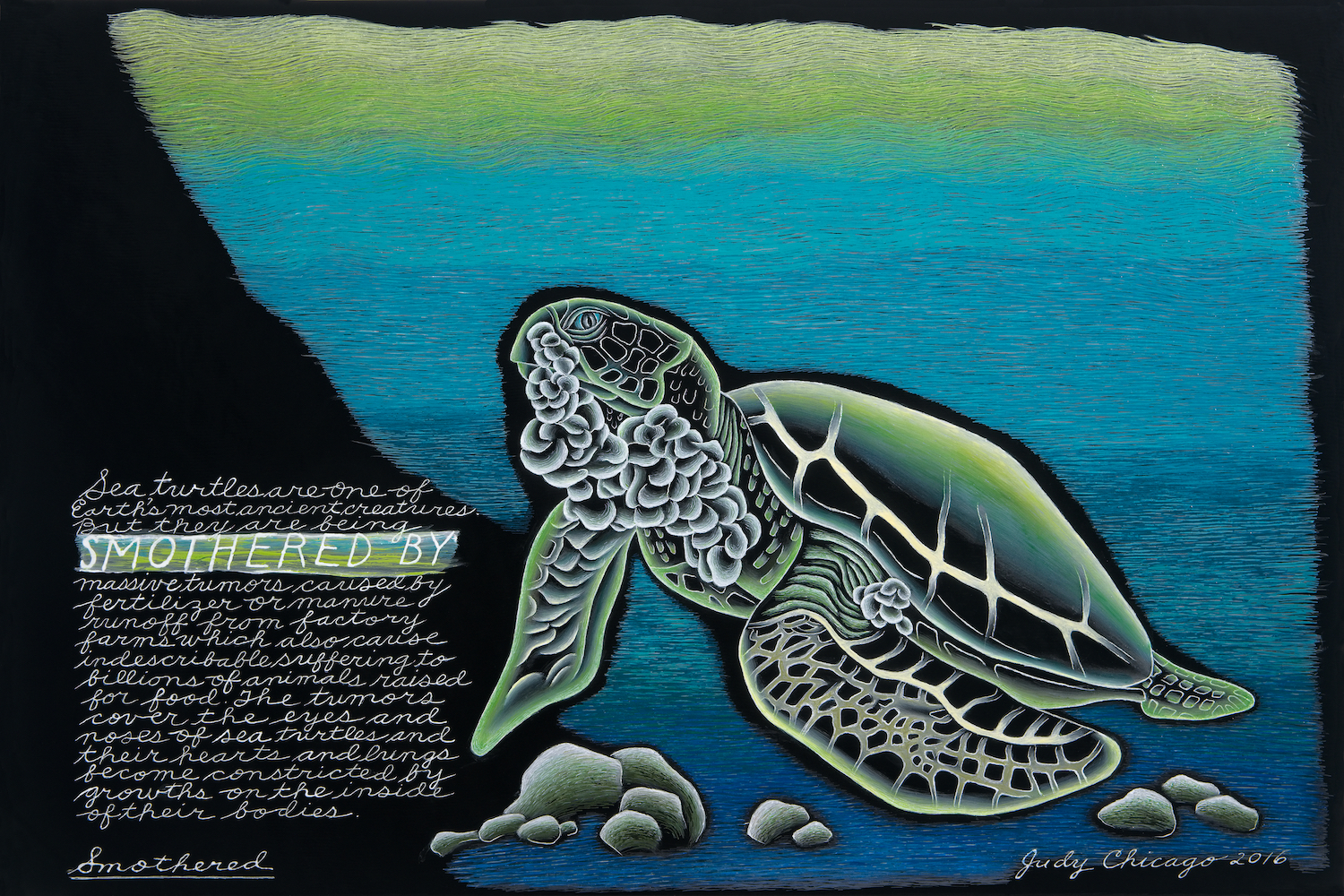

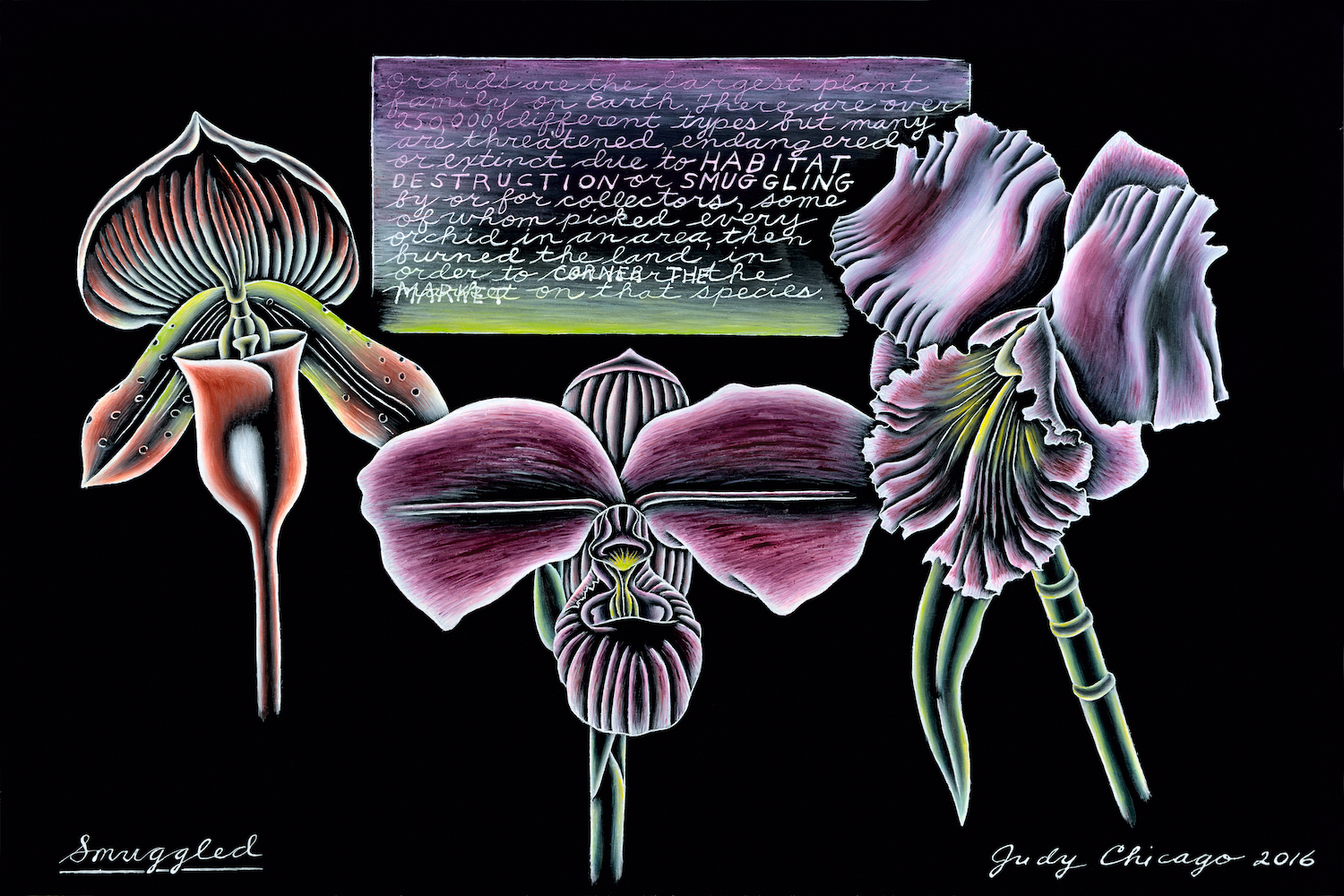

With strong fervor, Chicago alerts us of how dire everything is, her colorful depictions on black glass calling to mind velvet-painting kid crafts, or illustrations from a traumatizing picture book. Galapagos penguins are endangered by global warming and pollution; there are only 1,600 pairs of them left. Elephants, “the most caring, compassionate, and sentient beings on the planet,” are endangered due to habitat destruction and poaching, the artist writes on a panel depicting three elephants looking toward a mutilated elephant corpse. A tear streams from one elephant’s eye. The words “POACHING” and “HACKSAWS” and “MACHETES” rise up in threatening capital letters, almost stage-directing us to express shock and horror.

These images and the facts contained within them are indeed horrifying and sad. The issue is that many of these horrors are known, have been known, and are no longer shocking, unless one has ignored the news about global climate change or human rights abuses or animal rights abuses for one’s whole life (see also the palliative, denialist messaging propagated by fossil fuel industries and politicians, etc.). For me, the psychological effect of Chicago’s expositions of severe harm and animal endangerment—all directly or indirectly inflicted by humans—reminds me of those incendiary but well meaning brochures with photos of mangled chickens and cows that animal-rights activists hand out on sidewalks. Although I agree with the ideas, the forcefulness doesn’t seem effective on a passerby. Usually, I politely take a brochure and skim the text that explicates this abuse. My eyes skip over the brutal images.

Seeing these atrocities certainly can compel people to action, but how well does shock actually work? And what even shocks us anymore? The frank explication of climate-change facts—which Chicago puts forth in The End, and which scientists, organizers, journalists, and artists have been presenting for years—are terrifying, yet a complicit ambivalence still hums among us. And these things certainly don’t shock the industries accelerating climate change that have twisted the information and suppressed it to keep their coffers full. It is a tangle of disorganized priorities at an overwhelming scale.

Chicago’s dark paintings are glowing abyssal panes, a documentation of our violent epoch. But the hefty, oppressive voids from which the images emerge are also extremely fragile. We could break them; we could change course, they seem to say. This is also where grief settles in, potentially becoming useful. The stages of grief, as laid out by Kübler-Ross, are not actually so linear or clean. Compartmentalization, a psychological tool that enables us to at least temporarily set aside what causes us despair, is a kind of denial that can actually help us get to work.

Judy Chicago, “In the Shadow of Death,” kiln-fired glass paint on black glass (2015)

Judy Chicago, “Smothered” and “Smuggled,” both kiln-fired glass paint on black glass (2016)

The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction is on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts through January 20, 2020. For more info, visit NMWA’s website.

Featured image: Judy Chicago, “Bleached,” kiln-fired glass paint on black glass (2017)

Images courtesy of the artist, photos by Donald Woodman