TOKEN at Pyramid Atlantic

February 27 – April 6

Artists’ Panel Discussion on Tokenism: Friday, April 6 at 7pm

Multi-media collaborative exhibit among five women artists exploring issues of gender, sexuality, and class. Featuring Nina Buxenbaum, Zoë Charlton, Melissa Moore, Lauren Sleat, and Christine Buckton Tillman with an essay by Cara Ober.

for more information go to www.pyramidatlanticartcenter.org

Essay on Token by Cara Ober

token. n. 1. a characteristic indication or mark of something; evidence or proof: a ring in token of his love. 2. a memento; souvenir; keepsake: The seashell was a token of their trip. 3. something serving as an indication, proof, or expression of something else; a sign: Tears are odd tokens of happiness. 4. an item, idea, person, etc., representing a group; a part as representing the whole; sample; indication: she was the token woman in the room of men. 5. something that signifies or evidences authority, validity, or identity: The scepter is a token of regal status.

The Artist as Writer: Cara Ober

I had never been a token. At least, I didn’t think I had. I am a white girl from suburbia and have always blended in with my surroundings, even when I tried not to. This is both a blessing and a curse.

Recently looking at my high school yearbook I noted that, of my graduating class of approximately 500 students, there were just a handful of dark faces smiling out from the pages. This time, I realized that all of the non-white faces were extremely underexposed and dark, just silhouettes with white eyeballs and teeth. There were several Indian students, a couple of African-American ones, and a few Latinos with dark pigmentation, but the photographer didn’t adjust his exposure for these students. Maybe this was a technical error, or ignorance on his part, or maybe it was simple laziness. Either way, it is an apt and ironic metaphor for a token.

When you are a token, it is impossible to be invisible, but even more difficult to be seen. You don’t exist as an individual – you represent a larger idea or group. You are a figure of speech, an allegory. Everyone already has you figured out.

Sometimes you are accepted, recruited, or praised because your category is under-represented, all of which have very little to do with you as an individual. Other times, you are rejected, criticized, or ignored, for reasons beyond your control. When I applied for a job recently at a well-respected college, the employee in charge quipped, “Why can’t you just be an African-American woman?” She wasn’t being unkind. She was stating a fact. Apparently, my credentials were diverse enough for the job, but my skin color wasn’t.

When Zoë asked me to be a part of this show, I was surprised. So I inquired, What diversity do I have to offer? How is my perspective unique or different? I was informed, at that moment, that I was the token ‘artist-writer’ of the area – an elusive find among visual artists who mostly detest reading and writing. I had never thought of myself in this way before, and it was interesting. On one hand, I felt complimented, and on the other, insecure. Do I write about art because I love to or because my artwork isn’t ‘good enough’ to sustain me? Do most artists really fit into the stereotype of the non-verbal thinker? I had always assumed that this was not true.

When you are a token, sometimes opportunities come your way that you don’t deserve or expect. However, you do have the chance to make your voice heard, in your own language, by an audience that is new. There is a dichotomy inherent in tokens: conflicting extremes of power and helplessness, of visibility and invisibility, of fair and unfair. This notion of simultaneously conflicting opposites appeals to me in my own work as an artist. In the end, I agreed to write an essay about tokens, even though I had no idea what to say.

All of the works in this show speak to the duality of tokens and raise more questions than they answer. It makes sense: artists naturally look at subjects in multiple, conflicting, illogical, and fresh ways, leading to new conclusions without spelling it all out. The works in ‘Token’ are in conflict with each other in a sense, approached from multiple standpoints: scientific, emotional, sociological, and intellectual. This show in itself can be considered a token, featuring women artists who focus on race, class, and gender, although a close examination of the work and your own preconceptions may contradict this.

A Mark or Evidence of Affection: Zoë Charlton and Christine Buckton Tillman

“When a token is an object, it is both sentimental and completely meaningless in itself. I think of souvenirs, greeting cards, trinkets as tokens, and, at the other end of the spectrum, engagement rings.” – Christine Buckton Tillman

If trophies are supposed to represent victory and success, then why are they so damn ugly? A trophy can be a deer’s head, a brightly colored ribbon, a wife, a sports car, or a medal. Most often, they are tacky figures made of plastic and metal. Why do we need flashy physical reminders of our triumphs? And, why do we represent our precious successes so cheaply?

As artists, Zoë Charlton and Christine Buckton Tillman both use humor and irony in their work. They like to make provocative statements through jokes, and to challenge viewers playfully. Both artists excel at tweaking American pop culture, taking benign symbolic objects and subverting them. In “There Goes the Neighborhood,” a collaborative piece by Charlton and Rick Delaney, garden gnome sculptures with brown skin dot a sod lawn, a goofy joke on suburban ideals and their racial implications. Tillman’s series of plywood ‘cartoon’ log sculptures and faux wood grain creations raise serious questions about authenticity, preservation, and ecology through mischievous artifice.

It makes sense that these two artists collaborated and conceived a ‘joke token’ – investigating the conflicting power and helplessness inherent in tokens, but in a tongue-in-cheek manner. Headless and topless trophies are impotent and sad, but tender and funny at the same time. These trophies make it obvious that, without the right context, they are insubstantial and worthless. However, there’s something loveable about them at the same time. A token can never live up to the work, effort, and time spent earning them. Painted plastic and fake gold seem to be the best we can do to make ourselves feel important.

To me, these arbitrary trophies seem to champion all kinds of tokens and trophies everywhere. A ‘best effort’ award at attempting the impossible, a token can never live up to the huge and impossible expectations placed upon them. These trophies admit their own gaudy failures honestly and with real affection. They deserve credit for giving it their best shot. Their plastic and chrome hearts are in the right place.

An Indication , Symbol, or Metaphor: Zoë Charlton and Lauren Sleat

“I have felt like the ‘black sheep’ artist among the academics, an outcast if you will, the token odd one, the token ‘special’ one.” – Lauren Sleat

Charlton and Sleat are both storytellers, but don’t tell the kinds of stories most people are used to hearing. The word ‘narrative’ is thrown around in the art world today and represents a number of vaguely personal or historical approaches to art making, and Charlton and Sleat both combine the personal with the historical to come up with symbolic and surreal stories in drawings and in video.

After a brain storming session which ran the gamut of subjects from Sleat and Charlton’s obsessions with Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings, from real estate prices in the Boston area where Sleat lives, from pretty sunrises, to ponies, the women gave up and started filming. Charlton and Sleat hired a real estate agent to show them several properties in the Boston area, focusing on the idea of the ‘view tax.’ Similar to a ground rent, wealthy home buyers are asked to pay a fee for an uncluttered and ‘natural’ view out their front door. Rather than focusing on the homes themselves as obvious tokens of wealth, power and success, the two artists chose a subtler path and focused on the view.

Sleat and Charlton continued to shoot video and, after a accumulating a sizeable amount of footage, began to edit this into a narrative called “The Wolf and the Philly.” Approaching scenery, objects, and animals symbolically, Charlton and Sleat edited the video into a statement about race, implied violence, and, specifically, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings. A loose and organic process, this tightened as they edited the narrative together, with coincidental and specific details emerging and enriching the story.

Artists are lauded and also criticized for making ‘something’ out of ‘nothing.’ For the record, this is what artists are supposed to do – to approach the ordinary and turn it into something meaningful. How well this is done depends on the artist’s level of craft and dedication to research. In this case, finding a ‘common ground’ and working process that allowed both artists to contribute equally was crucial for the success of the work. Charlton and Sleat are consistent in their working process in their series of narrative drawings included in this show.

A Representation for Something Larger: Melissa Moore and Zoë Charlton

The Banjo Lesson by Henry Ossawa Tanner

“What first comes to mind when I think of a token is an after-thought, usually the only one in a group. However, I also see it (and this is sort of a conflicting notion) as a gift…not necessarily a gift of love or affection, but the ‘add-on’ or lone person is a gift because of what they may have to offer the group or situation.” – Melissa Moore

Melissa Moore is a musician. She makes ‘alternative’ music and, when performing or participating as an audience member, is often the only woman and/or black person there. The alternative music scene is active and vibrant in Baltimore, and is largely populated by young white males. Melissa acknowledges that she is probably not involved in the things she is “supposed” to be interested in, but pursues them passionately anyway.

Melissa and Zoë found common ground as artists over the banjo. It was an odd coincidence, but both women admitted to wanting to learn how to play this instrument and built their collaboration around it. Starting with the painting called “The Banjo Lesson” by the famous African-American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner in 1893, who studied painting in Paris because of American segregation, the two artists collected ideas and then moved in different directions. Moore created original music, based upon the old banjo song “Cleveland Marches to the White House” while Charlton crafted a piece of animation, combining with the painting with Melissa’s banjo playing.

After a bit of research, Charlton and Moore were surprised to discover that the earliest banjos were from Africa, made from gourds. It is ironic that African-American slaves created the first banjos in America, an instrument we associate today with country and bluegrass music and a mostly white audience. Historically, the banjo has had a central place in African American traditional music, and a strong, early influence on the development of both country and bluegrass.

In popular African-American music today, there is little interest in the banjo. Representing so many other ideas, techniques, and practices that African-Americans have developed that have been appropriated by the dominant white culture, the instrument, along with “The Banjo Lesson,” exist as tokens for what has been lost. Rather than rewriting history, the two artists reclaim their history in these works, exposing a small, brilliant token of African-American creativity and ingenuity.

An Item, Idea, or Person Representing a Group: Nina Buxenbaum and Zoë Charlton

“When I think of a token, aside from the ones used to get on the New York City subway before the advent of the Metro card, I think of the one ‘other’ in a room of ‘alikes’. I think of moments when in school I was asked for the ‘Black’ perspective on any given topic, as if I spoke for my entire ethnicity.” – Nina Buxenbaum

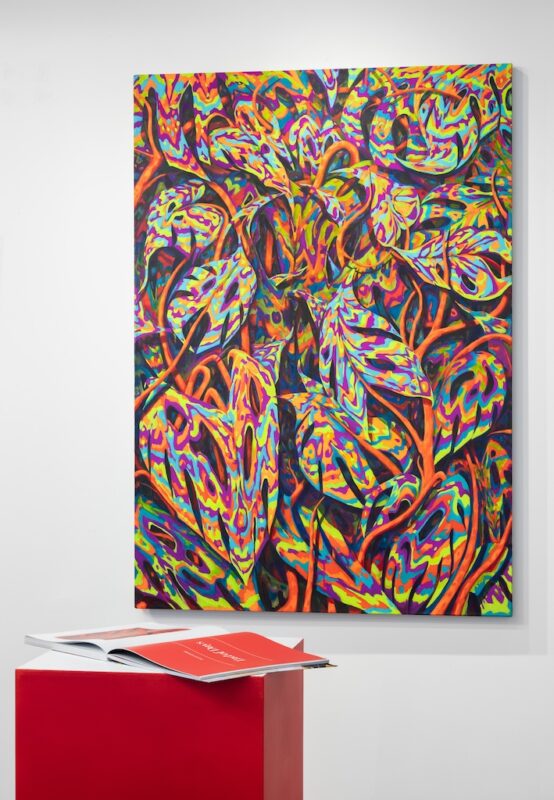

Nina Buxenbaum creates luxurious oil paintings in the style of an ‘old master’ painter. Her work reminds you of Ingres, Caravaggio, or Whistler. It is smooth and beautiful and easy to like. Buxenbaum paints portraits of African-American women in elegant surroundings, but includes subtle details in the props and backgrounds, which negate and question the validity of the visual beauty she crafts.

As collaborators, Charlton and Buxenbaum found common ground in their interest in art history, specifically, in challenging the typically white cannon that fills most art history books and museums. The two artists made several attempts at drawings in which each contributed equally to them, but they didn’t gel. Even though their ideas were similar, the distinct artist’s styles were too visually separate to work on the same page. After much discussion, Charlton and Buxenbaum decided on a different approach: to recreate a famous portrait painting with Charlton as the model in order to make a statement about tokens, both in an art historical context and a present-day one. Buxenbaum executed the painting on her own, with Charlton supplying a series of self portrait photos for painting references.

The two decided on Francois Boucher’s portrait of French courtesan Marie-Louise O’Murphy from 1752, later called ‘Blonde Odalisque.’ Boucher’s name is synonymous with the beautiful excesses of Rococo art, and, as the court painter of Louis XV of France, painted many sensual portraits of the King’s mistresses. Though a convention of the time they were created, Boucher’s works convey a powerful sense of the male gaze on the female model. Even today, Boucher’s presence as an amorous voyeur is felt as a powerful force in this painting; it confirms a vision of a specific male fantasy where the woman exists only to please men.

One notable change from the original painting, aside from Charlton in pink tube socks, is the model’s gaze. The original demure profile of the blonde odalisque has been changed to an aggressive frontal stare. With this subtle alteration, the nameless ‘token’ woman hanging in the art museum is now an active, unpredictable individual. She is no longer the object of pleasure that Boucher and countless other artists have depicted, instead she alludes to her own purpose and her own pleasure.

In this painting, Buxenbaum and Charlton play with the idea of the token black woman, a role both have played in their professional and personal lives. Historically marginalized and ignored, the ‘token black female’ has been inserted into a world that was historically forbidden, and rewrite history to allow her to be an individual, something a token is rarely able to do.

Conclusions:

“The definition of token is broad and it’s been interesting for me to question my relationship to other artists in regards to the word and also to see how the work developed based on the definition used.” – Zoë Charlton

In the end, each product in this show is as different as the method of collaboration used to create it. One thing that I learned from this experience is that the collaborative process is as mysterious and malleable as the process of making art. Rather than choosing a token drawing, token painting, token sculpture, and token ‘experimental’ video piece to flesh out a group show, the range of media in this exhibit reflects an authentic exchange of ideas and the process of finding the most effective way to express those ideas.

A computer screen, a piece of chrome, and a sheet of Rives BFK paper all function as recorders for our thoughts, the same way that poems, essays, and emails do. In the end, what makes artists and writers ‘tokens’ among the regular population is the work we do. As artists we represent facts, events, and feelings in unfamiliar and evocative ways. As artists we examine and indicate notions of authenticity and artifice. As artists we exist as evidence or proof that there is more to life than the traditional ideas that we are fed. I have found that all artists, including writers, exist as tokens: we are pawns, proof, reminders, souvenirs, symbols, symptoms, trophies, and manifestations of the culture we live in and the lives we lead.