Laura Burns has been making pared down, subtly political photographs for several years, taking simple images – dirt, parking lots, and now the human face – and turning them into instruments for social change. Most artists assume that, in order to tell a violent or complex or political story, their images must contain all the elements of the story. Laura Burns yet again proves that this is not the case.

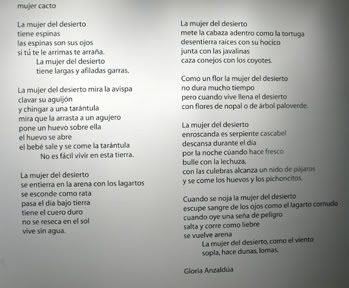

After earning a Fulbright, Burns chose to ‘study’ in Ciudad Jaurez, a Mexican factory town near El Paso. In Burns’ former works which depict various swaths of dirt, the photographer told the same story: after NAFTA, Mexico spawned miles and miles of factories called maquiladoras, based on cheap labor and no tarriffs. The people who typically work in these factories are poor women, who have migrated north from rural areas of Mexico, many who are supporting families back home. In the fifteen years since NAFTA, hundreds of these women, who typically travel and live alone, have been raped, tortured, and killed, and their cases remain largely unsolved. According to Burns’ catalogue essay, “The implication of this violence is a collusion between corrupt politicians, narco-traffickers, and U.S. demand for cheap goods.” Burns’ former photos of dirt, which appeared to be formal abstractions, and sometimes included a pile of actual dirt, were actually photos of crime scenes where these women were found.

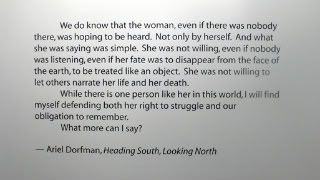

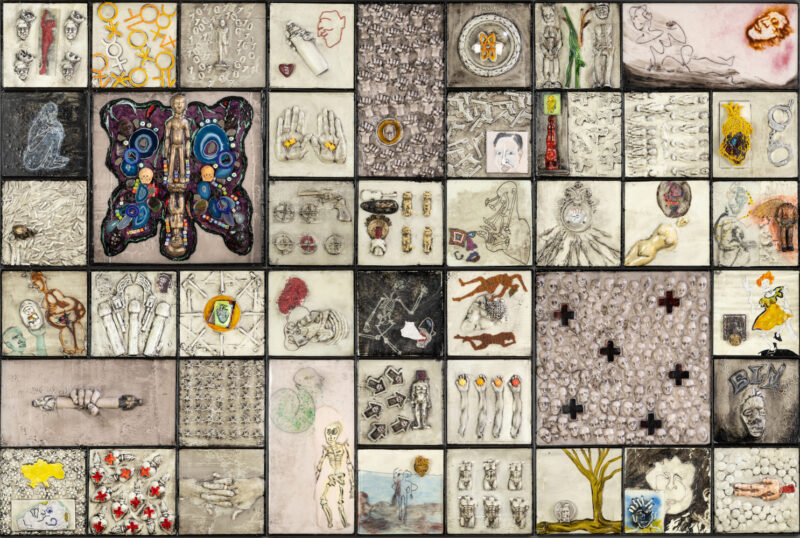

The Fullbright allowed Burns to spend a year in Juarez, and to take a more direct approach to her subject matter: photographing the women who currently work in the maquiladoras. Rather than taking a documentary or narrative stance, Burns photographed these women, some who became friends and others who were acquaintences, out of doors with a straightforward, passport-photo approach . Burns asked each subject to pose for a portrait as an individual act of homage to the “lost women” of Juarez, and the arrangement of the portraits together exponentially increases their power. Hung in a single row at eye level, the hundred or so faces express strength and solidarity with a striking familiarity.

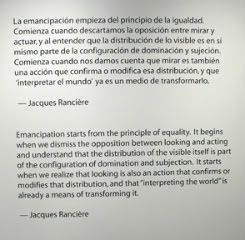

If Burns had arranged the exhibit differently – hung them in rows or a grid, like a repetitive Warhol series or a yearbook, the women would lose their individuality. Instead, there is an intimacy in each potrait which is palpable. The arrangement and editing in this exhibit, down to the barest essentials – faces interspersed with quotes in Engligh and Spanish – is crucial to its success. “Homage,” which has travelled to several Mexican cities, and is hopefully drawing attention to a tragic issue which has been neglected, comes across as solemn, honest, and terrifying – these faces contain so much more complex humanity than the stories we hear on the news and the statistics they represent.

– Cara Ober