To read the fabulous and star-studded Gutter Summa Issue, click here.

Mr. Jones and I: A Q&A between Cara Ober and Robert Sparrow Jones, as seen in Gutter Magazine.

Cara: Before you were a painter, you were a photographer. Do you still consider yourself a photographer? How did photography lead you to painting and how does it continue to affect what you create? How is ‘thinking in photography’ different than ‘thinking in paint’?

RSJ: I wanted to be a film director. Growing up in a small rural area in Pennsylvania my introduction to art came through the movies. I connected with the common man finding himself in an extraordinary circumstance and by the work of Truffaut, Goddard, Hitchcock and Woody Allen, I began making short films with a super-eight-movie camera. (You can see a later movie “Silverman” on UTube still!) Narrative is essential to my painting, I am the son of an English teacher and my interest in books fueled my passion for storytelling. The rich velvety black and white mise-en-scène in film led me quickly to photography and prompted the purchase of my first 35mm camera. I had stumbled across “The Americans,” by Robert Frank in our small library. It was a remarkable and haunting book of images I kept coming back to. Then I discovered Diane Arbus and Mary Ellen Mark. Vignettes of mysterious life are prevalent theme in my own painting. I tried to come close to something of a mixture between Frank and Arbus as I studied photography. Printmaking came naturally to me while I was into photography. The physicality of printmaking along with my propensity for expressive mark making took me to lithography. I was well out of school when I began painting but the results were immediate. The moment I made my first painting everything changed for me. I felt the summation of everything I loved about process and content come together in a new and transfixing way. This has never left me. Painting enigmatically embodied everything; storytelling, film and photography. I don’t consider myself a photographer now, though eight years ago I may have when I had a small exhibit in the Northwest.

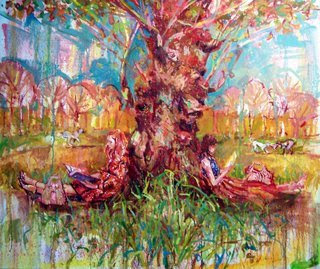

Cara: What is the deal with all your paintings of pretty ladies out in the landscape? Are these paintings fantasies or realities? Why are they usually outside? Who are these women?

RSJ: My narrative vision is a combination of many sources including, landscape, upbringing, faith, family and friends. As a boy I grew up in rural Pennsylvania and I was always outside. There is a definitive connection for me through nature. I daresay I find it spiritual. It’s a feeling. A feeling comes to me and then a story. The paintings are built from there. I was lucky enough to grow up around strong, intelligent woman. My two sisters, who are around my same age, have very individual personalities and strong opinions. I also have a sensitive younger brother who is an artist. My best friend from my childhood had three older sisters who were somewhat wild and ambitions and used to baby-sit us all the time. My best friend from middle school to this day has seven younger sisters. To me the people who are in my pictures are strong willed, curious and embody that

intellect by way of what I always think of as a distorted beauty. Beauty is an easy way into the painting. The “Prettiness” veils the dark mysteries that lay underneath. These paintings are not fantasy at all and inversely are convolutions of memory. I have become obsessed with memory and memory loss. Most these images are culled from childhood in one way or the other. And truthfully there are quite a few of my paintings with boys in them. It makes me think that they perhaps come across as less provocative but I am interested is the way that beauty of the image causes such a reaction.

Cara: You’ve had your work described in a number of publications and reviews, including your last show at Gallery Imperato being named ‘Best Solo Show of 2007’ by the Baltimore Citypaper. However, it seems like the reviewers always gets something wrong, either in their description of the work or in their analysis. If you could imagine the perfect explanation/description of your work — what would it say?

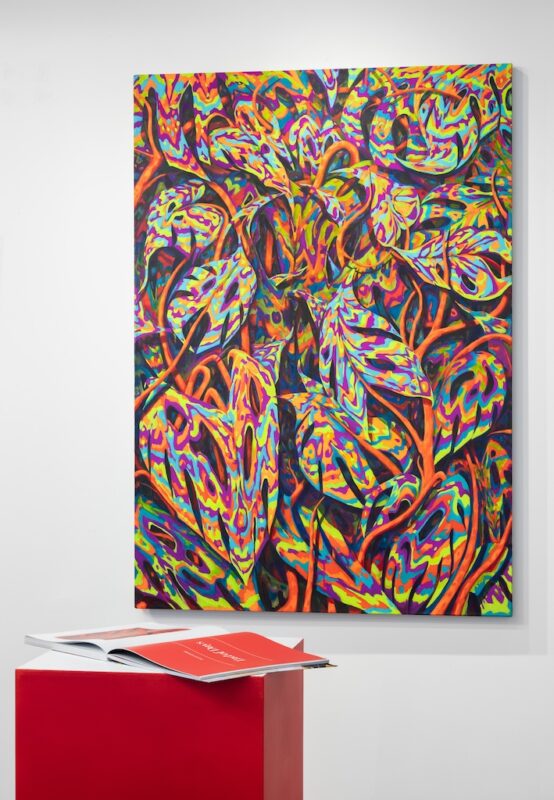

RSJ: I like to think of my paintings as movies. And I also know how ridiculous that sounds. Painting has a different dimension that film. This just how I see them. Using heightened color weights the image into something other than reality. I am playing with memory and movement. I like to think this color engages just the right amount of tension, psychology and emotional indifference. Apparent everyday scenes are experienced through the expression of paint are invested with meaning beyond the ordinary. Each work implies a chance for magic and wonder in an otherwise mundane scene. A typical painting presents an iconic subject underlined with subtle open-ended questions. An appreciation of the painting can be based on the straightforward narrative image or evoke a more complex interpretation and response. And maybe that something about it will be subtlety urgent and retain its burn in the memory. They don’t always do that but when I am making them I believe it is so.

Cara: Before you were known as Robert Sparrow Jones, you were simply known as Rob Jones. It’s a pretty common sounding name, much improved and more memorable with the sparrow added. Where did this name come from? What is the significance of the sparrow?

RSJ: The native part of me is lost or forgotten with my childhood. As a young boy I was always sleeping out under the stars, exploring the woods and building treehouses. I read a lot of folklore. I was attracted to the way birds are used as symbols. While I was in Seattle I made a documentary on the resurgence of the Canoe Nations. Spending time with the many tribes as we traveled with them up the coast was awe-inspiring. I wanted a middle name that was related to my upbringing and my interests. Sparrow is a master of flight and camouflage. As an air totem, the sparrow speaks of higher thoughts and ideals. She beckons us to keep our burdens as light as we can in order to avoid a heavy heart. Birds continually come into my paintings. After leaving the Northwest, Sparrow embodied a rite of passage; not to be forgotten—two lives now.

Cara: For all of the years you have lived in Baltimore, until this one, you were a long-haired hippie, often sporting a zen-master bun on top of your head. How is life different now without the bun? Do you prefer short or long hair? Please discuss the pros and cons.

RSJ: It’s funny you should say that. There was a reason behind my long hair, a story that is tangled and may involve murder. I never saw myself as the hippie type. I must admit though I am awfully green and have a working vegetable garden on my fire escape and compost and recycle everything. In short it was another spiritual thing. I have an uncle who is a priest and another who is a devout brother at the Vatican in Rome. I was always interested in religion, grew up Catholic but read about Buddhism and Native American spirituality. Right out of undergrad I spent some time in a monastery on the Upper West Side in Manhattan. I don’t know how long I grew my hair, probably at least eight years, maybe even ten. I just felt I didn’t need that bun anymore. And the moment I cut it all off, I felt a sense of lightness. I became more myself.

Cara: You attended the Hoffberger School of Painting at MICA to earn your MFA degree here in Baltimore. Do you have a favorite Grace Hartigan or MICA Grad School story?

RSJ: Grace and I got along straightaway. I was so interested her life. Grace can certainly tell a story or two and she has an impeccable eye for painting. Sometimes she would wheel into my studio and we would just talk about anything but painting. I helped her pack her library on Eastern Avenue. I remember the day Henry Cartier Bresson died I drove down to Fells’ Point and rang her buzzer. Grace, as usual, tossed a sky-blue argyle sock from a third floor window. The sock fell to the pavement and I took the key from the sock. There was a puddle in front of the door and I had to jump to get inside. Grace’s studio was becoming empty. I was packing her library into cardboard boxes. I labeled several boxes Ab-Ex and then five more Poetry. The day before we were talking about Frank O’Hara, she talked about him with such love. That morning she directed me to her bedroom to get something off her night table. There was stack of correspondence and she let me open a letter from Frank O’Hara. Then I saw a package marked “Utopia Parkway” and I gasped. She was delighted to bring out a small box and a story. In the box was a pennant made by Joseph Cornell, a heart with nails stuck into it. The next day she wore it to our Critiques. Grace and I got along well, although I think she was frustrated with me because I never answer the phone. I wish I could remember the gypsy song she sang to me once while watching a painting of mine.

Cara: You’re leaving town! You got a full professor job somewhere far away. Other than the money and respect you are sure to earn, what are you looking forward to most? Where are you going to, anyway?

RSJ: I will be teaching painting at the foothills of the Appellation Mountains in the North of Georgia. A small private College surrounded by bucolic green fields but close to Athens and Atlanta. I am looking foreword to the possibility of creating new work, both painting and writing. I know this change of landscape and lifestyle will create new ideas. I also plan to work hard at spending my summers traveling and researching.

Cara: What will you miss most about Baltimore?

RSJ: All my friends. Baltimore is a wonderful conundrum. Baltimore is full of outstanding artists, filmmakers and writers. I will miss everyone. I am often quiet but I rely on them. I will miss Carma’s Café, the dogwalkers, and beers at the Club Charles. My obsessive runs with my white boxer, Apple, up and down Stony Run, through Roland Park and behind Robert E Lee. My lonely Druid Hill Park runs in the dead of winter. The Signal on Fridays and espresso by the water on Sunday. Riding my old Schwinn through the city at 3AM. Baltimore, my Paris, my Tahiti, my wonderful and dear friends.

Cara: What do you think Baltimore will miss most about you?

RSJ: I don’t know, my mysteries. And my miseries.