Barry Nemett has exhibited his paintings in museums and galleries throughout the United States, Asia, and Europe. Since receiving a Fulbright/ITT International Travel Fellowship to Spain, he has lectured worldwide, curated numerous traveling exhibitions, and has been a recipient of resident artist grants in the United States, Japan, Scotland, Italy, and France. In addition, he has received many awards for his paintings.

Upon earning his MFA degree from Yale University in 1971, Professor Nemett began teaching at Maryland Institute College of Art, where he is Chair of the Painting Department. He has recently taught at Princeton University and, during the summer months, he teaches at the International School of Painting, Drawing, and Sculpture in Umbria, Italy. He has published essays and poetry for numerous magazines, and he is the author of a college textbook, Images, Objects, and Ideas: Viewing the Visual Arts.

Barry has recently completed his first novel, Crooked Tracks. I asked the author if he would be willing to discuss his writing process, the outlandish notion of a painter publishing fiction, and he agreed to an interview. For more information on the novel, or to contact Barnhardt Publishing , click here.

Cara: You have been teaching at MICA since 1971. Do you feel that being a professor of painting has had any significant effect—positive or negative—on your own work in your studio?

Barry: My first year of teaching was without a doubt my best year as a student. Being forced to talk about the craft and magic of the creative process enlightened me to what I knew—and didn’t know. I was forever saying things to my class that I had never thought of before, at least not out loud.

That said, I have to admit that when I first started teaching, I feared that, if I became too conscious of my thoughts about art, it would undermine my work in the studio. Pretty naïve thinking, but I was young. I didn’t realize back then how readily intuition, spontaneity, and “happy accidents” get into the (creative) act by slipping in through a side window when their counterparts, analysis and (schooled) decision-making, are seemingly filling up the front door.

To a significant degree, standing in the front of a classroom has informed the kind of considered decisions that take place when I’m home painting. After all, in order to critique and guide their students’ efforts, teachers have to develop the ability to articulate their thoughts. And, of course, what you talk about in the classroom has a way of following you home and into the studio.

Teaching has been an incredibly fulfilling part of my life. When I feel “on” regarding a lecture or critique, or a one-on-one conversation with a student, I feel a very similar kind of creative satisfaction that I feel after a day in the studio. It’s just a different kind of “out loud.” I’m sure a lot of artist/teachers feel that way, but I’m amazed at how few of them acknowledge it. I think it has to do with the idea that committing yourself to teaching somehow makes you less of an artist. This, of course, is ridiculous. Almost all the great artists today, and throughout history, Michelangelo, Raphael, Rembrandt, they were all teachers.

The main negative effect teaching has had on my studio practice primarily comes down to the time it takes away from my painting (and writing). But you have to do something to make a living, and for most of us, depending mainly on the sales of artwork for financial security can be pretty hairy. Sure, I wouldn’t mind having more uninterrupted time to just concentrate on my painting. What painter wouldn’t? But I cannot think of a better job for an artist than to be employed at an incredible college like MICA. The driven, gifted students there, and my colleagues, make teaching a joy, not a job.

Cara: After spending many years as a painter, painting professor, and curator, what led you to writing?

Barry: Painting, teaching, reading, and surgery led me to writing.

Painting—doing it, looking at it, teaching it . . . everything about it!—has opened me up to the joys, needs, and hurdles of expressing my feelings and thoughts in any number of different ways. Each art form feeds the soul uniquely. Yet all forms are related because they all spring from the same fertile ground.

It’s mainly a matter of time, training, passion, fascination (at best, awe), confidence, and, sure, familiarity (not in that order, there is no order) that determines how I go about communicating my feelings and thoughts. I see myself primarily as a painter (who draws constantly). But basically, at this point in my life, what I do in my studio comes down to gut questions like, “What do I feel like doing today?” and “How do I feel like doing it?”—today.

You asked how I went from painting to writing. Here it is. I focused on sculpture as an undergraduate student at Pratt Institute, focused primarily on painting in my senior year there and as a grad student at Yale. Then in 1971, immediately after graduate school, I had the good fortune to land a full-time teaching job at MICA. Like many of my colleagues, over the years I have accumulated a certain amount of information and insights (or, at least, opinions) which ultimately culminated into a book I wrote, Images, Objects, & Ideas: Viewing the Visual Arts (McGraw-Hill Publishers, 1992).

This textbook, my first serious writing project, evolved directly from my teaching, from conversations with fellow artists and my students . . . and, of course, from my own studio involvement, travels, and a lifetime of looking at great images and objects.

And from a letter that the French film director, Louis Malle, sent me.

In 1981 I saw “Pretty Baby” at the Charles Theater and thought it was a brilliant and visually stunning film. A Degas painting in motion. At the time, I was trying to teach myself to write, with very little luck. Mainly, what I had come up with amounted to a bunch of poorly conceived short stories and even worse poems.

When I returned home from the movie theater, I wrote a response to the film and was surprised at how fluidly it came out. For a change, writing was not a teeth-gnashing ordeal. When I showed my written comments to a friend, he encouraged me to send them to Louis Malle, the director of the film, which I did. I forgot all about it after I mailed off my letter, figuring Malle himself would never even see it because, not knowing his address, I simply addressed it to Paramount Pictures. But he wrote me an amazingly kind and generous note; he said it was the best thing he had read that had been written about his film.

Who knows, maybe Louis Malle was this really sweet guy who offered flattering comments like that to anyone who contacted him about his films. But who cared? His letter meant a lot to me.

That shot in the arm from one of my favorite directors, and my “fluid” experience expressing my thoughts, led me to determine that what I needed for my writing, at least for the time being, was to be able to bounce my thoughts off something tangible. The film satisfied this need; it allowed me to base my ideas on something to which I could continually and directly refer back.

In the form of articles, artist catalogue essays, and random reflections I would jot down just for myself, I started writing about all sorts of visual art works: film, painting, drawing, sculpture, ceramics, photography, architecture . . . which ultimately led to the publication of my textbook, Images, Objects, & Ideas. The book addresses a very wide range of art forms from the point of view of a studio artist, as opposed to an art historian.

That’s what got the writing started for me.

That and a bad back.

For quite a few years after undergoing several back operations, I found that my physical endurance was limited when I was painting. So I regularly took breaks, stretching out in bed or a recliner chair. But I didn’t watch television or read. I wrote. I’d go back and forth between writing and painting, and I discovered—and continue to rediscover more and more deeply to this day—that one form of creative expression informs the other.

Cara: How long did you know that you wanted to write a novel?

Barry: After completing the textbook, I wanted to write something else, but not another textbook. I was reading a lot of fiction, and I wanted to become a better, more sensitive reader. I wanted to better understand the kinds of decisions an author makes when he or she structures a sentence or chapter this way and not that or characterizes a scene, setting, or an individual in the story in a certain manner. I figured that since one of the best ways to understand what a painter is “up to” was to learn to paint, why not teach myself to write stories as a way of learning to read them better?

I’m a digresser. In case you hadn’t noticed. This always reminds me of that, and “that” I find I can often most vividly describe through a story. So I guess it was natural for me to move from nonfiction to fiction.

After publishing the textbook, I started writing poetry again and then some short stories—with a little better luck this time. One of the stories was about a sixteen-year-old boy and a tragic episode in his life. A writer friend of mine, Jean Rubin, read it and suggested I try fleshing it out. “Why not develop it into a novel?” she asked. So I did.

“So I did.” No, that’s too cocky. I don’t want to make it sound like it was a snap, because it wasn’t. It’s not like I was a natural writer—I’m not a natural “anything.” But I’m a great plodder. My children were in middle school when I started work on “Crooked Tracks”. They were in college when I finished. But I loved every minute of struggling over it—even the hair-tearing ones.

Cara: You attended graduate school at Yale for an MFA in painting, I believe. Recently, I attended a lecture in which you showed slides of graduate work and, ironically, these paintings were all of books. I think we saw over one hundred different paintings and drawings of hardbound books, each kind of crowded together Morandi-style, and each a bit different. What was your relationship with the subject matter at that time? Why were you painting books with such intensity?

Barry: Each time I do a reading or presentation associated with the recent publication of “Crooked Tracks,” I do it differently. The Johns Hopkins talk was the first time I showed such a range of book paintings and drawings in over twenty years. I did that because the books worked well with several passages I wanted to read that evening. The passages from the novel were included in a chapter called “Sad Eyes,” in which I introduced the grandfather figure, one of the main characters in the novel. He was a man of books. His apartment was filled with them. When I wrote this chapter I literally placed all around me the few still life book paintings that I have left from this period, and I used them as inspiration and visual references for my description of the setting.

To flesh out the grandfather figure in the story, I combined elements of my own father and grandfather, as well as a dear friend of mine, Dr. Richard Kalter, all of whom have passed away. The actual books, on which I based the series of still life paintings that I just mentioned, were originally my grandfather’s. He had read them over and over again, but he gave his books to me after he developed eye problems and was no longer able to read small print. I was very close to my grandfather, so those books of his that he cherished spoke to me with meaning and distinction.

At Johns Hopkins I showed 120 images of books. Some of the actual paintings are 15 feet long, some just 15 inches. I know it sounds heartless, or at least over-the-top, to subject an audience to so many variations of the same subject, but since I was showing images on two slide screens, I was able to click through all the pictures in less than five minutes, while I read from my novel. In fact, I created more than 1,000 paintings and drawings of books around the time I was at graduate school, and it was a kick for me to connect that period, almost 40 years ago—God, am I that old?!—to this time of my life.

You asked, “Why was I painting books?” Well, I was painting cityscapes around New Haven, Connecticut, and, initially, I saw the flat planes of the books and their arrangements as metaphors for buildings and, later, landscapes. Being a night person, in the evenings I liked being able to set up, in effect, little tabletop cities in my studio and control the artificial lighting and everything else, and then go ahead and take as much time as I needed to portray the set ups. I guess this is an example of how still life painting offers a kind of godly approach for the artist, isn’t it? “ . . . And God said: Let there be light, and there was light . . .” because all the still life painter has to do is move the lamp a little to the left or right, and, Voila! there they are, sunshine and shadows, just the way you want them.

Book Grouping with Central Figure, 1972, Charcoal on paper, 48 x 96 inches

After expanding into cityscapes and landscapes, I scaled the books down and they became more intimate (anthropomorphic) stand-ins for figures, family groupings, friends, actual people I knew. I had a book for me, a book for my wife, Diane, one for my friend, Eddie . . . The still life ensembles suggested interpersonal relationships. Human narratives.

Couple, 1971, Gouache on paper, 4 x 6 in

Diane, 1972, Oil on canvas, 6 x 9 in

Why so many? The short answers are: “I don’t know,” or, “It seemed like a good idea at the time,” or “I just felt like I hadn’t gotten it right yet,” or “I kept saying to myself, ‘Just this one last time.’”

Here’s a longer response: The more you look at something, the more there is to see; the more you learn about anything, the more there is to learn; the more you do something, the more other (not always better, but “other”) ways of doing it come to mind. My early involvement with the book series taught me this. For me, there’s always been this need to play out one line of thought as fully and inventively as possible before I go on to thinking about something else. Maybe I’m just slower on the uptake than other people, but to gain the depth of understanding that I’m looking for, I have to take my time, which has never bothered me. What’s the rush?

Sure, repetition can breed boredom and redundancy, but it can just as easily generate ever-new discoveries. Surprise and unpredictability are not limited to the “latest game in town.” In fact, one of the reasons artists work in series is the (often unconscious) realization that familiarity leads to the unfamiliar. After all, you don’t want to repeat yourself, so you make it your business to find a fresh way of seeing what you have already spent a long time looking at. One’s first take on a subject tends to focus or settle on the surface. The artist’s job is to dig.

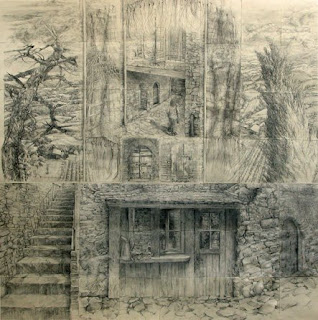

Incidentally, to bring this discussion more up to date, I should add that that’s one of the things I like about continually returning to the small hilltop town in Italy that I have returned to for the past four summers. The more I paint the landscape views from my studio in Italy, the more I want to paint them. They change every day. And so do I.

Cloud Watching, Umbria, 2008, Gouache on paper, 60 x 84 in

Cara: As a painter, you’ve collaborated with other artists and writers in visual works, and often included texts in paintings and installations. What is the relationship between these “interdisciplinary” visual works and your novel? Is one an extension of the other?

Barry: Like most painters and writers, I spend an inordinate amount of time in my studio alone. Nonetheless, I’m a very social person and crave the company of others. I once wrote in a catalogue essay for a traveling show that I curated called “Conversations”: “If I were a boxer, I suspect I’d be a counter puncher.” I like responding to “the other.”

Gatherings 12, 1994, Gouache on paper, 38 x 180 ft

I have collaborated with other artists, as well as non-artists, my whole life. I’ve worked in the studio with my children, Laini and Adam, since they were four or five years old, and now that they are gifted, sophisticated artists in their own right, periodically we continue to combine forces. Laini and I have created numerous large, mixed-media projects, and, like this past month in Italy, we often paint alongside one another from the same subject matter, pooling our resources. A few years ago, I served as the production designer for “The Instrument,” a film that Adam wrote, directed, and co-edited. (Actually, this wasn’t just a collaboration between Adam, me, and a bunch of other individuals—it was a collaboration between MICA and Princeton University, as well.) Thirty years ago, I collaborated on a fifteen-foot painting with my nephew, Josh Rosen, when he was about six or seven, and on numerous occasions over the years, I have collaborated with my dear friends and fellow MICA faculty members, Howie Weiss and Bob Salazar. And, of course, for more than a decade, I incorporated Richard Kalter’s poems into my mixed-media polyptychs.

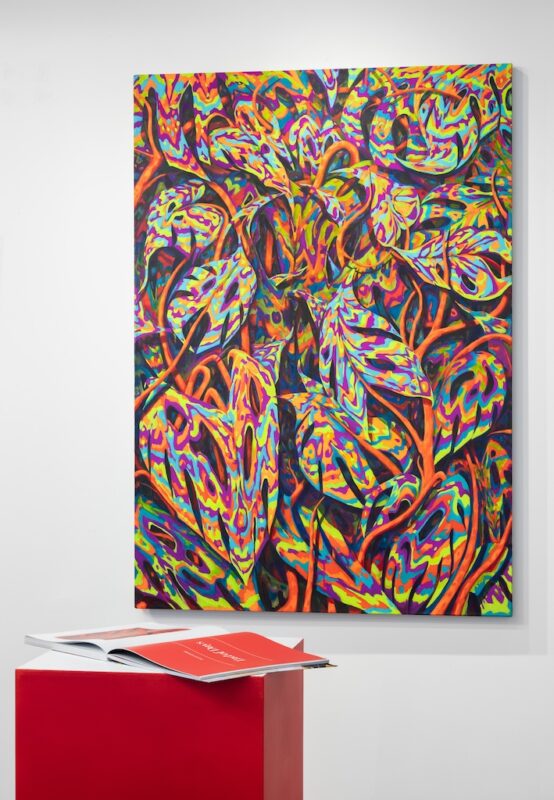

Even for the upcoming show of my work that will begin at George Mason University on September 1st and will continue traveling for the next year and a half to other venues throughout the U.S. and abroad, I am working with one of my best friends, the sculptor, Stuart Abarbanel. Our collaboration will be the largest work in the show. He’s carving a sort of frame that includes miniature wooden doors that echo my drawn images of doors that punctuate the two-dimensional part of the project.

I’m comfortable with a lot of stuff going on in my life at the same time, and, perhaps reflecting this, my most sustained, ambitious art works, the projects of mine that make my heart pump hardest, are usually the ones that have the most “stuff” going on in them, the ones that are the most densely loaded. (Some would probably say, “overloaded.”) Viewers of my work can get lost in a kind of hide-and-seek thing. I’m okay with that. I’m not a Minimalist.

I guess what you refer to as the “interdisciplinary” aspect of my novel, and of many of my collaborations, as well, is a more delicate way of recognizing what my mother used to refer to in regard to my work as “busy.” My novel, “Crooked Tracks,” weaves together prose, poems, and color reproductions of paintings and sculpture. In this respect, my writing probably does represent an extension of the kind of complexities that I inevitably find myself building into my visual artwork.

Talking about “Crooked Tracks,” while I was writing it, I created about a half dozen large, mixed-media wall installations (one was 6o feet long, another was 40 feet high), and full-size room installations. Switching back and forth between these visual constructions and the written story was invaluable. And thrilling. The installations allowed me to see and touch and actually walk around inside what I was writing about. Again, one form of creative expression informed the other.

Crooked Tracks 3, 1998, Mixed Media Room Installation

Cara: Do you think the artist’s brain and the writer’s are more similar or different? In your experience, what are some similarities between the two processes—writing and painting—and some differences?

Barry: From my personal experience, fiction writing and painting are more similar than different. Vision, revision, and invention—I see both the fiction writer and the painter building their foundations upon components such as these, as they struggle and juggle and plod their way toward communicating their ideas.

Vision: what one has to say (in paint, clay, stone, words, etc.) when it is a reflection of how one sees the world. Painters and writers strive toward a common goal: to create a certain kind of reality (which, of course, has nothing necessarily to do with any kind of realism).

Revision: Artists try it one way, then another, and another, until they get it right (whatever that means), or as right as they can get it. As far as I’m concerned, revision is probably the most important part of any creative process.

Invention: you want to express, as inventively as possible, whatever it is you have to say. After all, what you are saying is probably not all that earth shattering. More often than not, it’s how you say it that makes the difference between something that resonates and matters and something that doesn’t. Think about all the crucifixion paintings that fill up art history. They all say pretty much the same thing. It’s not what the artists had to say in those images that distinguish one canvas from another, it’s how they said it. Or, putting it another way, how they said it was what they said.

Yeah, the visual and literary arts are similar in a lot of ways. Regarding similarities, my experience dealing with the challenge of learning to write benefited greatly and repeatedly from just asking myself when I got stuck, “What would I do in this situation if I was standing before a canvas holding a brush?” I found that more often than not, there was a surprisingly close, readily available equivalent when I simply allowed myself to recognize it.

I’ll give you an example. My gridded, multi-paneled works present many of the very same kind of problems and solutions that I find when I’m writing. A significant challenge in both forms of expression involves moving from one section or panel to another. Like paragraphs or chapters in a book, for me, each panel in my multi-paneled works (“Passages,” is an example) represents a complete composition, yet it functions as just a small part within a larger structure.

Passages, 2008, Graphite on paper, 24 x 92 inches

In writing, there are stops and starts, as well. Each sentence, paragraph, and chapter represents a potential break in the flow. What’s the most inventive, dramatic, graceful, (and sure, sometimes the most intentionally disruptive or jarring) way to move the reader from this point to that? The author has to answer these questions just like the visual artist does.

There are endless other examples I could think of that speak to ways in which writing and painting are similar. As for differences, I guess the two biggest ones involve words and time. Words: writers use them to communicate their ideas and to evoke visual images. Painters use paint. And Time: you tend to see a painting all at once, or almost at once; you just have to be able to step back far enough. That’s not the case with reading a novel. It doesn’t matter how far you step back from the book, because having to turn the page(s) prohibits that all-at-once thing I’m talking about.

I could go on all day about the differences and similarities between painting and writing. There are plenty of both. Sure, they represent two different languages, but they have in common the same kind of overall challenge to communicate, and it’s the mystery and bliss of communication that I’ve been trying to address.

Painting is fundamentally a visible experience, which, at best, takes on a quality of reality in the viewer’s imagination, while fiction writing is fundamentally an imaginative experience, which, at best, takes on a kind of visible reality in the mind of the reader. But they overlap exquisitely.

And they both feed the soul.