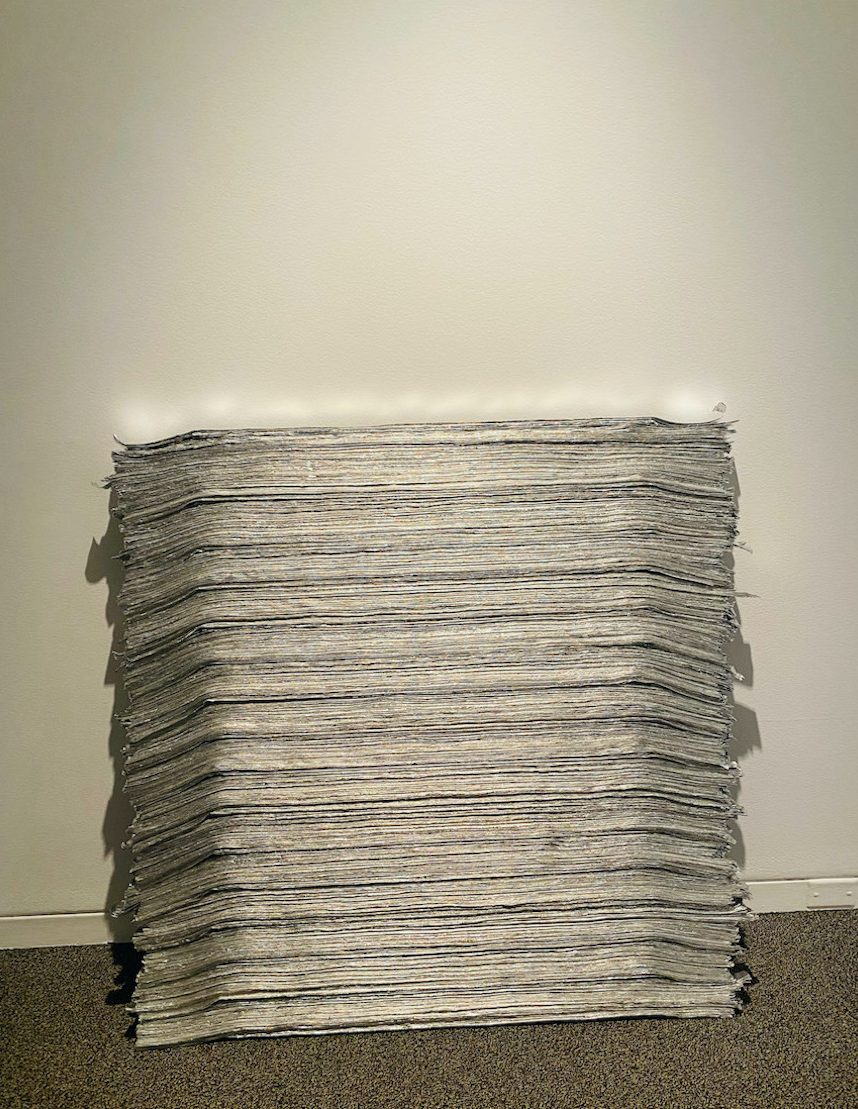

Hae Won Sohn’s “/skwer/ I” is one of the first sights that catches the eye when entering the Janet and Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize Finalists exhibition from the Walters Art Museum’s lobby. The aluminum-foil-and-metal-hardware artwork leans against a far wall like an aloof attendee at a posh party; from a distance, “/skwer/ I” has the shiny, silvery sheen of a beaded flapper dress. As you get closer, that detached glamour sublimates into a more obdurate presence. That glossy brilliance is due to spotlights hitting lengths of aluminum foil folded into long, thin strips that are stacked one atop the other. It only takes up a small portion of the wall it leans against, but it has the imposing presence of a flyweight boxer whose hands you don’t want to catch. And it doesn’t look like something familiar, but it also doesn’t not look familiar. What, exactly, is this thing?

I’m using the blunt-object noun “thing” here to tap into the word’s fugitive meanings and Kantian philosophical fussiness. The fact is I have no idea what, precisely, to call “/skwer/ I”—sculpture? 2D object? Metalwork?—and this low-key inscrutability is what makes Sohn’s Sondheim exhibition such a thematically rich and visually captivating snapshot of an artist exploring the untraveled rapids created by the creative flood of her own ideas. The Baltimore-based Korean artist was trained in traditional-to-contemporary Korean ceramics techniques as an undergrad in Seoul and continued her studies of craft at graduate school at Cranbrook, where she also began experimenting with materials and processes.

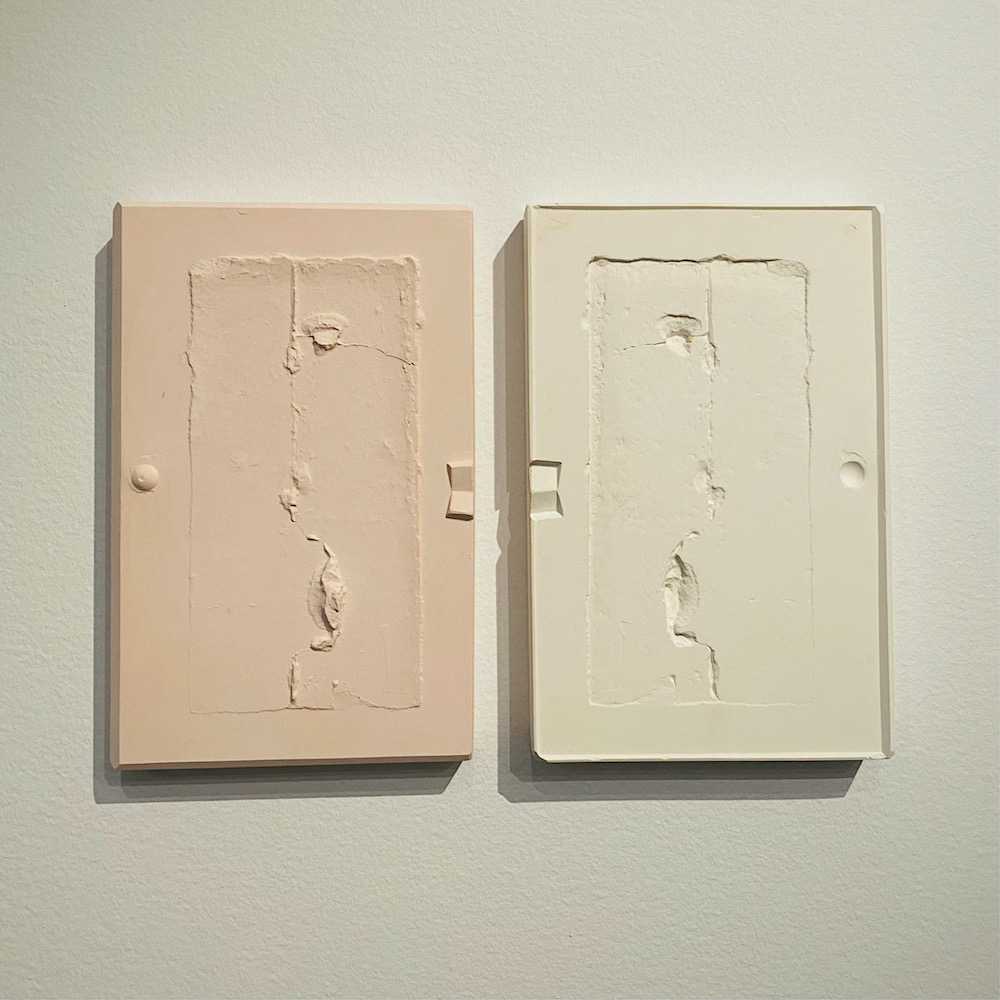

The artist describes the evolution of her own practice best in a Baltimore Clayworks artist lecture in March (watch on YouTube), and in interviews, where she talks about how her experimentation introduces moments when she has to improvise along the way. Sohn uses commercial ceramics techniques, such as slip casting, which are overwhelmingly used to create uniform multiple objects, and experiments with the process at various stages—such as breaking the molds and reassembling them—to create unique objects that can’t be mass reproduced.