Bret McCabe on For Whom It Stands and The National Anthem Remixed at The Reginald F. Lewis Museum

The ambient mix was drifting into the boring. During the first segment of The National Anthem Remixed at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture, the Baltimore Boom Bap Society treated “The Star Spangled Banner” as one element in an entire world of sound.

The duo of producers/musicians Erik Spangler and Wendel Patrick set up their DJ gear in the museum’s second floor theater, with Spangler laying down a watery wash of textured electronic sounds while Patrick tapped out the anthem’s melody on a toy keyboard. It was an abstract interpretation of the song that wandered further and further away from the recognizable song as they improvised their mix. Snippets of hip-hop lyrics, spoken-word performances, and other anthem interpretations peppered their sound exploration, charting a movement through time (Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock) and place (one sample shouted out a RIP to Derrick Jones, the Baltimore activist and hip-hop artist who passed away this summer).

It was a woozy adventure, but like improvisations do sometimes, it started to feel like a run-on sentence that didn’t know where to put the period. Then Patrick and Spangler settled into a bouncing, jazzy, Madlib-ian groove and vocalist Jasmine Pope (aka J Pope) walked to the area in front of their gear. She picked up a microphone and laid into “O say can you see . . . “—words branded into most American’s brains by rote memorization in primary school and turned in de facto ritual at sporting events—as if it were a classic soul song, and it was like the heavens opened up and the angels began to weep.

An interesting fact: According to the United States Code, Title 36, Subtitle 1, Part A, Chapter 3, Section 301 that pertains to the National Anthem, during a performance, members of the armed forces and veterans may salute, while “all other persons present should face the flag and stand at attention with their right hand over the heart, and men not in uniform, if applicable, should remove their headdress with their right hand and hold it at the left shoulder, the hand being over the heart.”

Another: In 1942 the U.S. Congress approved the Code for the National Anthem of the United States of America recommended by the National Anthem Committee, which provides regulations for the performance of the music. It should be played in A-flat for band or instrumental performances. Musicians playing it should stand. And it should be performed only in “situations, programs, and ceremonies where its message can be effectively projected.”

These were some of the rules governing the national anthem that local beat boxer Shodekeh, the musical curator of the National Anthem Remixed program, learned while researching its music and lyrics. This performance came at the end of a weekend that wrapped up a three-year Star Spangled 200 celebration of the bicentennial of the War of 1812. The festivities included appearances by Gov. Martin O’Malley, President Barack Obama, and concerts and a fireworks display broadcast on PBS.

The event is expected to be a tourism boost for the city, bringing people to town to commemorate the Battle of Baltimore in 1814. That was when American forces at Fort McHenry held off a British bombardment and inspired Francis Scott Key to write a poem that became the lyrics to the “The Star Spangled Banner.” Those words, paired with a popular British song written by John Stafford Smith, became the national anthem in 1931. For many of people, the anthem and the flag are secular symbols of American identity that have accrued sacred status.

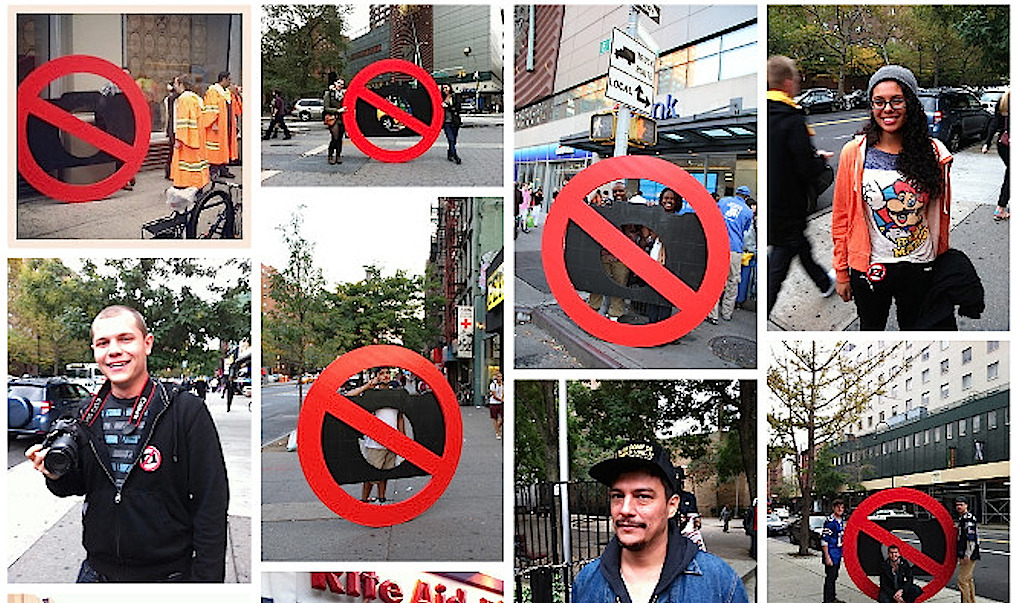

The Reginald F. Lewis Museum’s For Whom it Stands exhibition confronts those cultural assumptions head on through its collection of historical artifacts and original artworks. (Both this writer and Bmore Art editor Cara Ober participated in Atlanta photographer Sheila Pree Bright‘s “Fifteen” installation, which hangs outside the second-floor entrance to the gallery.)

As curated by Michelle Joan Wilkinson, who became the curator of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in March, the exhibition catalyzes a more complicated, deeper reflection about the flag and what it means to be an American than a mere programmatic response. It includes, among other items, information about Grace Wisher, the 13-year-old indentured servant who helped Mary Pickersgill sew the flag that flew over Fort McHenry; a 1942 photography series by Gordon Parks featuring Ella Watson, a government charwoman supporting her five kids on an salary of $1,080 per annum that yielded Parks’ “American Gothic.” In addition, it features Cliff Joseph’s arresting 1968 painting “My Country Right or Wrong,” a haunting landscape featuring a series of black and white figures blindfolded by the flag standing atop a ground overrun with decomposing human remains and bombs sprouting like shrubs from the carnage. Joseph was a co-chair of New York’s Black Emergency Cultural Coalition that objected to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900-1968, an exhibition ostensibly about the black American experience but, as Joseph recalls in a 1972 interview:

“One of the things we were in protest against was the fact that Mr. Schoener chose not to use the talents and expertise of any of the members of the black community—artists, art experts, leaders—to help in setting up the show. One other omission was the fact that there were no black painters or black sculptors included in the exhibit. This was especially hard to understand since the show was supposedly set up for the purpose of showing to the public the cultural contributions that had been made by members of the black community.”

For Whom It Stands is a powerful reminder that who tells the stories of the American experience matters. The National Anthem Remixed points out that stipulating how one should perform and experience “The Star-Spangled Banner” is an exercise of political power as well. It’s a song and lyrics with a thorny history in and of itself— historian Ted Widmer recently wrote a reminder essay on Politico that Key was not only a slave-owner but a slavery defender. Key’s brother-in-law was chief justice Roger Tanat, author of the Dred Scott decision, and remembering that kinda makes you wonder who was and wasn’t included in Key’s idea of the land of the free.

By the time Jasmine Pope finished her stunning rendition of the anthem, the Boom Bap Society’s program, titled “The Rocket’s Red Glare,” felt like a reflective essay in sound: a way to work through late 20th-century versions of the song and recast it in a more contemporary musical setting. Classical Revolution Baltimore took a more subtly radical approach with its “Stripes & Broad Stars” segment. This small classical ensemble—trumpeter and music director Rafeala Dreisin, violinists Evelyn Petcher and Blaire Skinner, flutist Stephanie Ray, tuba player Dan Trahey (artistic director for the BSO’s OrchKids), and cellist Johnny Walker—played a gorgeous version of the anthem first, with the tuba and cello providing the rhythmic pulse, the violins handling the lyric’s melody, and the trumpet and flute accenting that melody. The ensemble then ran through five variations of the tune, changing the rhythm to a marching stomp, allowing the violins to interpret it as ephemeral duet, going through it backward, and incorporating different material into the familiar melody.

It was slyly adventurous approach. Instrumentally the ensemble included staples of European music (the strings), popular music of the 19th century (tuba and trumpet were often components of brass bands, a British import that became popular in America), and, in stroke of understated aplomb, the flute, whose singing tone somewhat recalls the chirping upper register of the fife, which popular culture has mythically associated with the American revolution. It was a cheeky way to point out that the elements of this American anthem were imported from elsewhere, and to demonstrate that this instrumental grouping is capable of interpreting the anthem’s melangé in a variety of equally moving ways.

That adventurous streak continued in the a cappella performance. A five-vocalist ensemble—beat boxers Shodekeh and Max Beats, hip-hop MC B-Fly Denai, mezzo soprano Alana Kolb, and Celebration vocalist Katrina Ford—sumptuously ran through the anthem before venturing into their own variations. Shodekeh and Max Beats sculpted percussive textures as Denai recited names of African-American women killed by American law enforcement officers and Ford and Kolb harmonized behind her. Ford began a riff on “let freedom ring”—a lyric cribbed from Samuel Francis Smith’s patriotic song “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee,” whose melody is the United Kingdom’s anthem, “God Save the Queen”—and turned it into a haunting mantra, her singular voice answering the “let freedom ring” call with an the resigned response, “in spite of everything.”

It was a impressive feat of minimalism, transforming a pair of 18th century tunes into something close to a spiritual by combining elements of hip-hop and human voice. It led into a finale involving all three ensembles that was a bit too much. With Classical Revolution set up stage left of the Boom Bap Society, the vocalists grouped stage right, and Shodekeh acting as conductor in the front, this large ensemble tried to find a group articulation of the anthem. It never quite gelled. Beats competed with strings competed with voices competed with Shodekeh rhythmic inventions competed with everybody else. There were just too many ideas flying around at once, yielding a Babel of the anthem. Bits and pieces of the familiar melody poked through but the overall impression was closer to a Glenn Branca guitar symphony without the overpowering, hallucinogenic unison.

What the finale lacked in experiential cohesion it made up for in metaphorical oomph. The evening’s entire program was a celebration of the sublime interpretive power of musical variation. This finale merely demonstrated that there can be moments of harmony in that noise, that there’s enough space in the anthem for different ideas and voices to coexist. Every performance of the anthem is an individual’s interpretation. And maybe, just maybe, the idea of being an American can be as flexible and improvisational as well.

For Whom It Stands runs through Feb. 28, 2015 at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum.

Author Bret McCabe is a haphazard tweeter, epic-fail blogger, and a Baltimore-based arts and culture writer.