An hour later I get good news. My doctor calls and says that the chest X-rays show that I do not have any blood clots, which was his primary concern. I had no idea blood clots were even an issue, although recent articles indicate it is a major cause of death with younger Covid-19 patients, and I am grateful he hadn’t told me before this. He says my lungs still show signs of pneumonia but look better than when I was in the hospital. I feel jubilant and healthy. Finally. I’m halfway there.

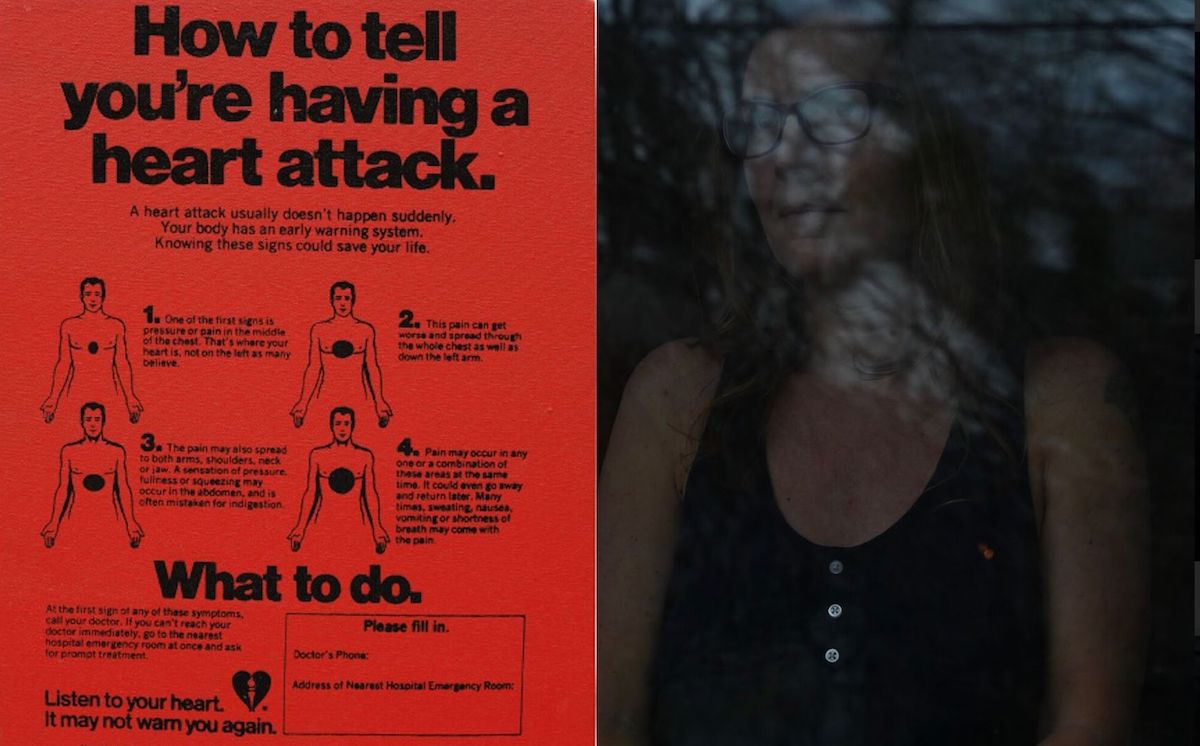

Scheduling the echo proves more difficult. I spend countless hours on the phone listening to elevator music, playing phone tag between doctors and receptionists before being told that cardiologists are only taking “emergency” cases and I don’t qualify, despite my doctor’s STAT order. I get it. We are experiencing a complete breakdown of our healthcare system and every doctor and healthcare worker needs to create protocols that protect them. All non-essential medical procedures have been cancelled. I understand, but I’m still having chest pains.

For many who got critically sick with this virus, recovery is complicated and unpredictable. We don’t have any data around how long it takes to get back to normal, or whether we are actually immune, or what symptoms may still show up. There is very little health care available for anyone who is sick—this is not safe or effective, but our system has been pushed to the brink of catastrophe.

My doctor finally scores me a cardiology appointment at an office near his, about an hour away from my home. I have to wait two weeks for the appointment, but I am flooded with relief because it means that I will finally have confirmation about the condition of my heart, which may require medical intervention.

I wear a facemask and douse my hands in copious amounts of hand sanitizer in my car before entering the medical building, which is unusually dark and quiet. On Wednesday, April 22 I am the sole patient in the cardiology office. The sonographer is petite and blonde, her face covered by a medical mask. She is the only medical professional here, except for a receptionist who checks me in from behind glass. The empty waiting room has about 30 chairs and every other one has a printout taped to the seat, instructing patients not to sit there to keep social distancing protocols in place. I do not sit down.

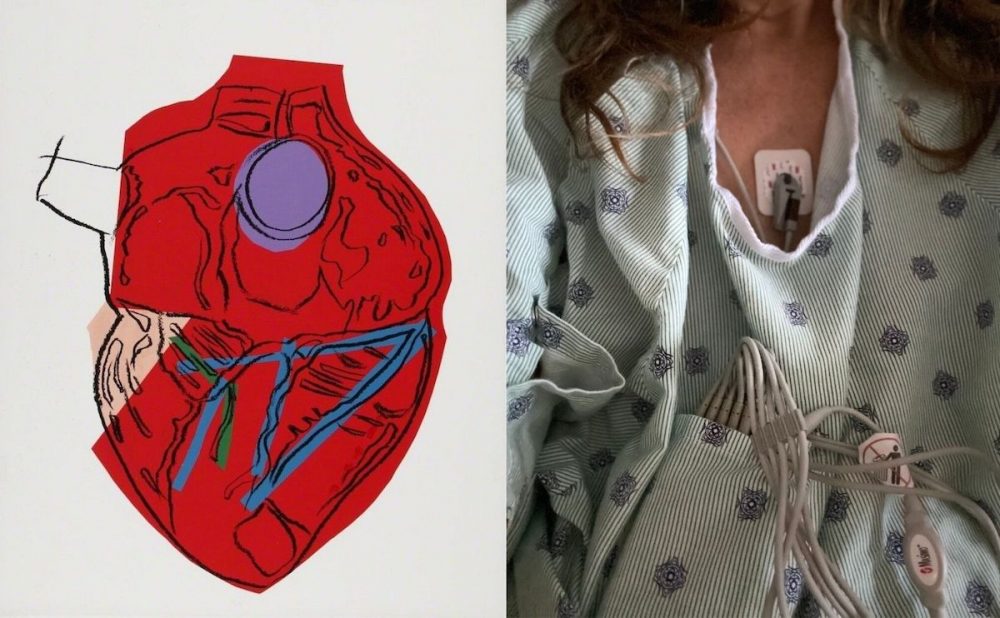

After weeks of waiting and worrying, where my chest pains varied from nonexistent to medium, I am finally in a cardiology office that only conducts tests two days a week, and I am terrified about what this test might reveal but thankful to be seen. I enter the examination room and put on the blue paper vest. The sonographer places stickers around my chest and attaches wires to them. Then she instructs me to lie on my left side, which immediately causes pain intensified by the anxiety I am feeling.

She places the ultrasound wand covered in warm goo against my chest, prodding gently into the exact spots where I am feeling pain. As she navigates my heart’s valves and chambers, taking photos and video of the pumping action in my chest, I imagine what it could be like to live with a damaged heart from now on. Occasionally the sound comes on, a WOW… WOW… WOW, with the staccato percussion of my heartbeat underneath. It sounds so fast. Is my heartbeat elevated because of my fear? Is it throwing off the test? How can you tell if your heart is healthy?

I have never ever felt anything except for a vague sense of camaraderie towards my heart when exercising, a general sense that it’s fun working together. Now I have to wonder: What if my future is suddenly cut short or I spend the rest of my life dealing with the impacts of an illness that are only now becoming known? After the exam, I wipe off the goo and the ultrasound tech tells me my test will be analyzed by the cardiologist the next day, and then my doctor will call me with the results in a day or two. I have no idea what to expect and the sensation of pressure in my heart is more potent than ever, but I also feel relieved.

We have so much free time right now and the news is a constant barrage of changing information and absurdity. I try to focus on work, but my mind travels in a million different directions and the world feels so different now. All the illusions about available and competent medical care and the efficacy of the USA navigating this crisis based on the professional expertise of epidemiologists, doctors, and economists are gone. There is no organized system for battling this virus, medically or economically, and realizing that, more than ever, we are all on our own and it’s luck more than anything else that can protect us, is demoralizing.

What we are dealing with is unprecedented in every way. We are suffering from a complete lack of normalcy and all that is left is insecurity. We are so much more vulnerable now than before, and those who get sick with Covid-19 are at the mercy of a federal administration that has willfully ignored the advice of epidemiologists since January—because it’s an election year and the president wants the economy to go back to normal, but without actually doing anything to make it happen. This laziness and lack of trust for the professionals prepared to rebuild our country, based on science and proven research, is staggering.

No one makes their best decisions under duress, and our healthcare system has been utterly depleted by the Covid-19 pandemic. Although the USA is home to thousands of epidemiologists and some of the world’s most esteemed doctors, apparently few of them work for the federal government anymore and none of them were included on the president’s coronavirus task force. As a nation, our healthcare system has been hobbled and stymied by an administration that aimed first to cover up the virus in order to stabilize the stock market and is now using this health crisis as a pulpit for misinformation and cringe-worthy self promotion.

Despite claims to the contrary, the US is still failing to provide even the minimum level of testing needed to get our economy on track. As a country we are unable to take care of those who need it most, especially the elderly and communities of color, making already vulnerable populations that much more so and creating economic instability for everyone. As the wealthiest country in the nation, we should be able to proudly come together with generosity and science-based strategies to combat this virus and to equitably distribute economic resources to everyone who needs it because we are all connected, our survival is collective. This is in the best common interest of everyone, rich and poor, but it’s been several months and the only discernible federal outcome that can be counted on is bad reality television.