From the first album, Songs of Praise, to Drunk Tank Pink, to the latest Food for Worms, the music of shame seems to show your post-adolescent rage, self-identity and introspection, and thoughts for friendship. Drummer Charlie Forbes also said in an interview with NME about the process of writing the second album, “We were trying to be too clever.” Do you think you were being extra cautious about songwriting?

I think it’s funny because all the stuff they say about album cycles is so true. Your first album’s easy because you’re writing all this music with the intention that no one will hear it. And you do it over while you’re playing gigs and learning how to compart yourself in the industry or whatever. And then you continue to the second album; I think it is kind of easy to become too conceptualized in a sense. Or maybe the music you’re listening to and became so obsessive over it that you think I want to sound like this. You maybe push it a bit too hard, and it becomes slightly overthought. I think previously, we’d be in a situation where we’d have ideas and immediately pigeonhole ourselves and say, “This doesn’t sound like us,” or question ourselves like, “Is this gonna work for us?”

And this time, we went with the ethos of “if it sounds good, let’s just do it.” We didn’t put too much conscious effort into sounding like anything. I think, which I find weird as an artist, people want a coherent album. Whereas for me personally, my favorite albums have always been incoherent. People are just writing whatever they want and being influenced by many different things. If I listen to an album, I don’t just want to hear the same kind of song ten times. I want to hear people putting their toes off the line or dipping their feet in the water of something else. And I think we’ve always liked being eclectic in our songwriting, where we like to throw curve balls, mix things up, and not allow ourselves to be defined as a specific genre. We just wanna do whatever we want.

The vocal part of Charlie Steen has also changed significantly from the first album to the latest Food for Worms, with more melodic singing. Compared with the earlier shame, it seems to soften vocally in a way. Do you think Steen made any conscious changes in how he interpreted songs?

When we first started, the band was not particularly musical—you know, he was a fantastic writer—but he had never really played instruments. So I think it always would end up being a scenario where we’d come up with all the music first, and then he’d have to fit himself into that afterward. We wanted to avoid that on this latest album, and I think we wanted the vocals to take center stage, which would be the opposite of when the music fits itself around what he’s doing. I think that allowed him to come out of his shell vocally in the sense of not just doing spoken word or his trademark of shouting over the top and singing more.

He also discovered that playing an instrument while singing would help him create better melodies and go along with the music a bit more like he wrote the baseline on “Adderall (End of the Line)” and “Burning by Design.” So that lent the songs a new kind of dynamic vocally. I was writing a lot of vocal stuff as well, Steen and I would work very closely together where I’d play something on the acoustic guitar, and then I’d have some melodies and some lyrics, and we’d build a song from that. I’d say this album was effortless—no arguing or dramas—and it was easy.

Do you think shame has attained some musical fluency? Would it be scary or exhilarating for you when it happens?

I don’t know. Honestly, we feel like old timers now, like being in our late twenties and feeling so weird. I hope that our music is influencing people. I don’t know if it is, but I hope so. Getting famous is definitely not something I’ve ever fantasized about, but it’s definitely crossed my mind when we go to certain places and see genuinely famous people, like backstage at festivals. And I think the whole idea makes me think that would probably be my worst nightmare, which is why I’m happy I’m not the frontman. That would be exhausting. It seems like some people love it and then also hate it at the same time.

Speaking of writing music, I’ve always felt your guitar sounds are characteristic, which has crystal brightness. Are you intentionally making the sound with a certain style for the band?

That’s definitely something Eddie and I have always liked when it comes to guitars. It kind of cuts through to the point. That’s the beauty of having two guitar players in a band. If you form a perfect relationship and synergy, you can create great textures and a wall of sounds. We are so in tune with each other now that if someone’s playing rhythm, the other will automatically be playing leads. It’s almost like a symbiotic relationship. I think as the guitar plays, you become very stubborn because you want everything to sound like it always does live. It’s quite hard to change that sometimes. On this album, I started mainly playing acoustic guitar and certain things that influenced guitar sound, such as the live album, MTV Unplugged in New York, by Nirvana.

I love how that sounds with a kind of rawness and the liveness of it and how Kurt Cobain picked up acoustic sounds. That was a significant influence on me, like Bruce Springsteen and Jeff Buckley, when it comes to guitar work. Their albums are just so fantastic. Let alone the amazing vocals, and it’s just how crisp and beautiful everything sounds. I think that’s what you strive for being a guitar player.

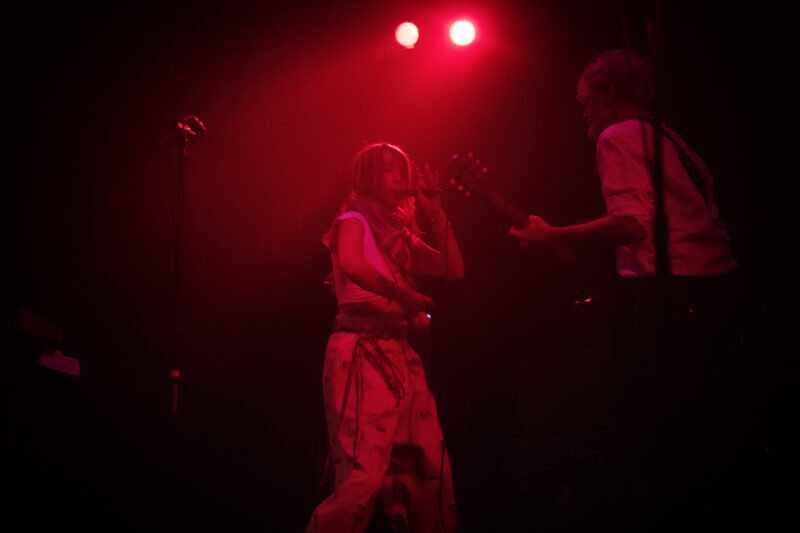

shame plays the Ottobar this Friday, May 12th with special guest Been Stellar (Doors at 8, show at 9).

Tickets are available through the Ottobar’s website.