Baltimore back then, the film scene was John Waters and Barry Levinson. That’s kind of pie in the sky and inaccessible. But then all the stuff that Skizz [Cyzyk] was putting on with MicroCineFest…

SPW: Skizz was, as far as I could tell, the leader and he also worked at the video store where I worked, so I knew him personally. And that’s how I even knew about things happening, because he would say, “Oh Sean, you should come with this” cause he was working there with me at the store. We had another employee at the store who had a short film that played before Brothers McMullen at Sundance and we thought “Man. This guy made it. He made it.” And then I don’t think he ever made anything else.

NP: Well, I mean, why continue when you’ve touched the fucking sky? Played before an Edward Burns movie?!

SPW: I think that we were not thinking that [they] were going to make it.

NP: To what Sean was saying earlier, my mother lived in Alexandria, Virginia, for a number of years, so kind of around the same time we would have both been in the sort of DC-Baltimore Metro area with some regularity. I’m a couple of years younger than Sean, which isn’t much, but the difference between nineteen and seventeen is kind of vast.

So my memories of Baltimore are also kind of tied to the 90s and also to having to have my mom drive me up so I could go to Reptilian Records in Fells Point and Atomic Books back when it was still in Mount Vernon. But I couldn’t stay over or anything like that. Also kind of echoing what Sean was saying, I feel like in the 90s DC and Baltimore were on kind of equal footing in terms of cool stuff that was going on.

Maybe over the last 20 odd years most of the weirdo culture stuff has gone up to Baltimore, and DC is really, if not entirely, a much more kind of white collar, bureaucratic city. I think there was still some kind of cultural sediment going on, which I get a little less of a sense of [now]. I don’t think at the point, when either of us would have been spending time there, that Baltimore had quite the cultural cachet it would have in the late aughts or some time after that.

NP: Yeah, which is too bad ‘cause there was plenty of cool stuff in Baltimore, like Atomic Books, I’m pretty sure it’s Atomic that was there, now it’s totally in a different place, right?

It’s up in Hampden now.

SPW: And then Reptilian… I mean, Soundgarden is still around, but even that is a much cleaner, cuter version than what it was.

NP: With Sean and myself being in our mid-40s, when we got to New York it was probably the tail end of it seeming like you could still have a low-overhead existence and do cool stuff. By the end of the aughts that seemed to be less and less feasible to people. You had a lot of people and bands, or people who were kind of doing art that didn’t have a great potential for profit, who were going to Philadelphia and Baltimore. Even the DIY spaces in New York… I never really bought into the legend of 285 Kent, for example. Like who wants to go to a DIY space and see fucking Ryan Schreiber of Pitchfork in the corner? There’s something slightly dubious about that. Whereas you set foot in Tarantula Hill and that looks like the real thing..

SPW: Now I can’t even find the flyers I used to keep for all these things in those places. I don’t know where they are now. When we were preparing, I was looking up Tarantula Hill online and it just said: “Closed”. But then I was in Baltimore with Eric Hatch and Jimmy Jimmy Joe Roche, they were like, “No, I think he’s still there. Let me make a call.”

It felt like time traveling. All those places in Baltimore, they don’t exist anymore, “Now you’re telling me I can go?” When we did finally get to check it out the next day, it was pretty unbelievable.

Was the sensory deprivation tank still there?

SPW: There’s two.

NP: One of them’s in the movie.

SPW: Yeah, though it kind of just looks like a girl getting out of the shower. But anybody who knows the place would get that joke. We’re so happy about that. You know, some of the road signs after they leave Baltimore, the names of towns and the road I grew up on, are there. And it’s a joke for nobody. No one will laugh, and maybe you were in the place where somebody lives on Blue Ball Road.

I think Twig’s not in town anymore. Eric Hatch was saying he thought that after you shot, his lease on the place was expiring in two weeks.

NP: If I remember correctly, he was getting ready to outfit a van to live in.

SPW: Oh yeah, he was getting the van ready, or maybe it was ready. But I mean, is somebody buying that place and doing anything with it? It’s a pretty authentically difficult part of town to bring people to, I think.

And we had an adventurous night filming there. We had some security, and pretty early on there was a fight with the security guard and a local. The security was local, so they knew the terrain.

NP: Do you recall what the conflict was, Sean? Our security guys knew where to find him, went to his apartment, got our traffic cone back which honestly we probably could have lived without.

SPW: That’s right. Yeah, the traffic cone was just the beginning. Then there was a block party developing right around back from us. And the numbers of the party were growing and growing. And our security guys at one point said, “You guys might want to start wrapping this up.” They’re gonna be drinking back there and it only takes so many brilliant ideas before they’re in your movie.

NP: I also remember when we were setting up craft services in the road between that little piece of like “wasteland” and Tarantula Hill, one of the guys from the neighborhood came up and was like, “You’re gonna wanna get that packed up before it gets dark, because that’s when the rats come out.”

SPW: Also, I had a friend who was a locations guy in Baltimore and whenever there was a film production around there was like this kind of scam of guys coming in getting into fights with locations guys and stuff just so that they could sue Disney or whoever was in town. I said, “Well, we’re not Disney. You’re not gonna get much money from us if you try to sue us.” Our crew is mostly like 20-25 year olds who’ve never been to Baltimore. We took some of them for crabs earlier, those that we could spare for like two hours.

I’m interested in the “tense” of the film because you guys talk a lot about the movie itself, like the satire or prodding that it’s doing is very current, but a lot of these spaces you’re approaching seem to be more from your memories of 2004 or 1998.

SPW: All the guys living in that house are definitely not very contemporary. I’m sure those are fashions somewhere, probably in Eastern Europe. They’re modeled after a 90s idea of crusty punk kids. The costume designer and I, we very much were doing a 90s, or almost like Repo Man sort of styling of the people that are living there, and it seemed to suit that.

I was a little insecure when we were shooting because Twig was there, he’s in the movie. I don’t want him to think that we’re making fun of the place cause I sincerely just love this, to be able to go and be a part of something that I wasn’t a part of, you know?

NP: The contemporary world isn’t all the contemporary world. There’s a lot of 1998 that’s still around. There’s a lot of 2006 that’s still around, depending on where you are. I can go back to Cincinnati and probably four nights a week a garage rock band is playing. The things that have existed there’s still going to be, at least in some places, a passionate audience for them.

Even in terms of production design, the house that the Lawrence character [Simon Rex] lives in—I think a big mistake that a lot of production designers make is they don’t think about the sedimentary layers that various generations leave in a space. And I think a lot of the worst period production design is like a movie set in the 1950s, and you don’t see any of the 1930s there. Whereas, realistically, living in 2023 I can still find bits and pieces of 1935 and 45, and so on. It is a throwback, but those throwbacks exist in the world to this day.

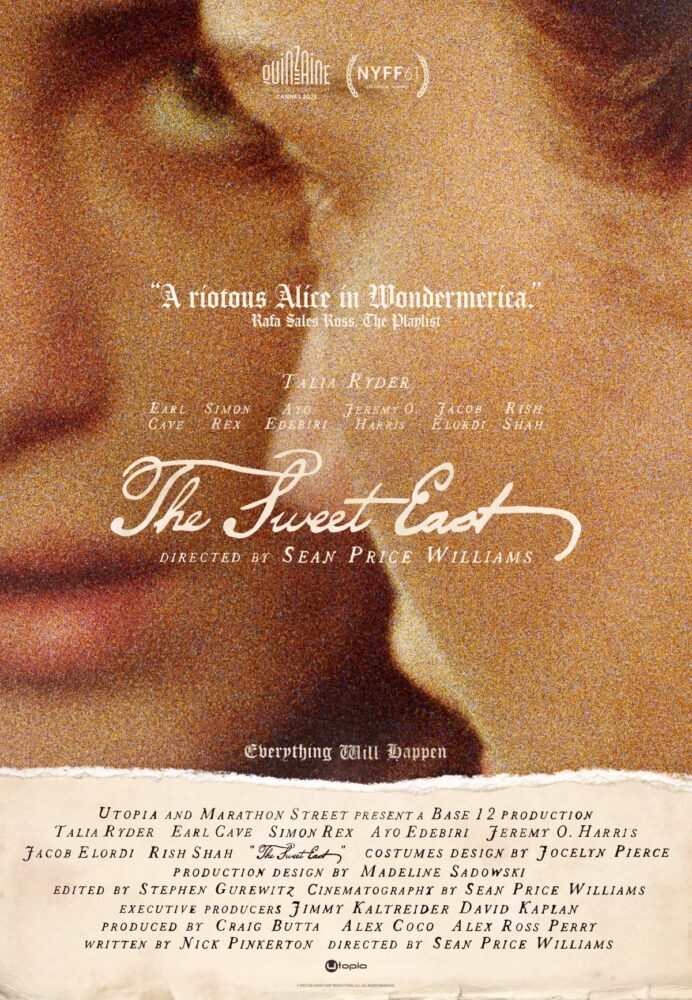

People do choose to live in a time, even if it’s not the time they happen to be living in. I think, for Sean and myself, we’re not necessarily creatures of the 2020s. If you look at Simon Rex’s character, this is somebody who decided he’s just gonna live in the 19th century. Whereas when you get to New York, and I think this is kind of true to New York—at least true of the kind of “cool kid” crowd that Talia’s [Ryder] character starts running with, it is very of a moment, even if that moment is made up of other recycled moments.

It’s not something I’ve really thought about that much before, but I think in some ways it is kind of a time travel movie. It’s not all contemporary, it’s people who have decided that they’re going to attach themselves to one era or another. So, Talia’s our little time traveler.

SPW: One more Baltimore thing. I was in Scotland for two months working on a movie, shooting on 16mm, I was like, “You guys you need to see what 16mm is gonna look like. Let me show you Pink Flamingos.” And people in Britain—there’s a few brilliant movie people—but for the most part, they don’t know anything about movies anymore. They’re so reduced to streaming and working. The reactions to these guys watching Pink Flamingos was just unbelievable.

When I told them I watched this with my parents when I was a teenager that blew their minds. It was the most disgusting, worst thing that they had ever seen. And then it’s on the Criterion Collection. Sure enough, it’s not the blow job, or the prolapsed anus, or the things that are really disgusting to me—that dogshit eating just was too much for them to handle, and I couldn’t believe it. In 2023, fifty years later, it’s still the most shocking thing these people had ever seen.

NP: And Divine eats that dogshit—just to bring things full circle—in Mount Vernon, right outside of the original Atomic Books location. That’s what they call a “kicker” in the journalism biz.