Skip Norman: Here and Now, featuring recent restorations of all the films, is “an exciting point of discovery for folks who might be curious to know what kind of work was being made in the 1970s by a Black man who was obviously incredibly talented,” said NGA’s film programmer Joanna Raczynska, but who “had little luck finding [financial] support for his art in the United States during his lifetime.”

“These lesser-known names [like Norman], but not the lesser artists,” she added, “are incredibly important to the history and practice of independent filmmaking.”

Initially produced as one film before being separated for distribution, Washington D.C. November 1970 and Black Man’s Volunteer Army of Liberation offer rare contemporaneous footage of Black Power activities in DC from late 1970. Washington D.C. November 1970 captures images from the registration site of the Black Panther Party Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention. This gathering, organized by the newly set up DC chapter of the BPP, was intended to draft a new US constitution but foundered over poor logistics and run-ins with uncooperative local authorities.

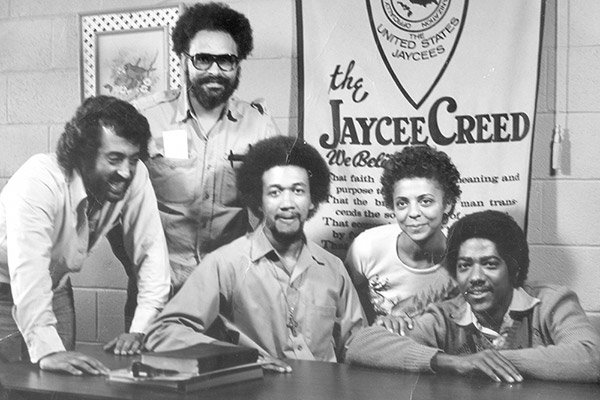

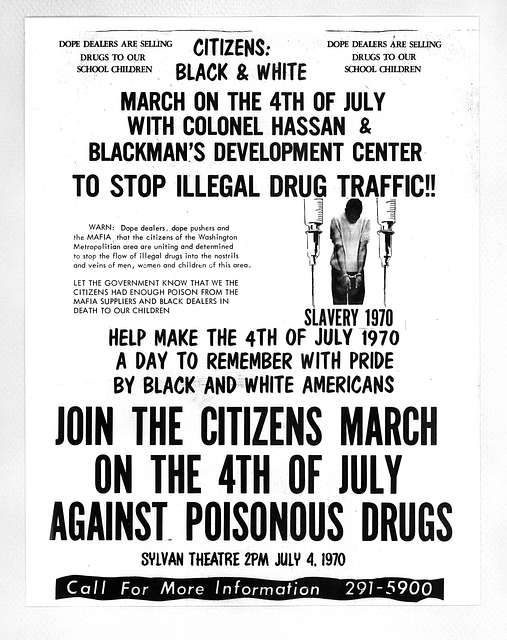

Black Man’s Volunteer Army of Liberation focuses on the drug treatment program, as well as a range of other self-help initiatives, of a nationalist group of that same name in the District. This group had deep roots in DC, robust membership, and even garnered public funds to support its drug rehabilitation activities, explained University of Maryland Baltimore County’s Dr. G. Derek Musgrove. Dr. Musgrove, an expert on Black Power activism in the capital, said in an interview that while some photos of the Blackman’s Volunteer Army of Liberation from that era were available, he hadn’t seen and wasn’t aware of other film footage of them as extensive as Norman’s film.

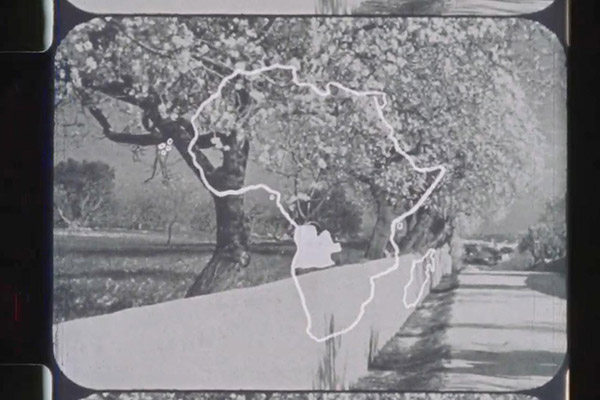

The two films demonstrate Norman’s keen interest in race, leftist politics, and structural critiques of systems of oppression but also the range of his approaches and aesthetics. Washington D.C. November 1970 has an experimental tone, combining narration readings from W.E.B. DuBois and Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver with montages of portrait stills of American presidents contrasted with Black leaders, occasionally overlaid with sketched drawings.

Black Man’s Volunteer Army of Liberation uses a sympathetic but more straightforward, almost news reportage style to document the group’s activities, including interviews with its leadership, clients, and wives of the members as voice-overs to the visuals. Both films are valuable in adding images from the District and of this particular homegrown DC faction to the small body of Black Power films from that time period, such as Agnes Varda’s Black Panthers (1968) and Leonard M. Henny’s Black Power: We’re Goin’ Survive America (1968).

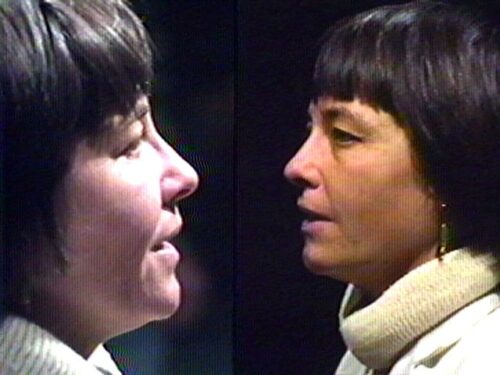

Wilmington 10—U.S.A. 10,000 situates the plight of political prisoners wrongfully imprisoned in the 1970s within the history of systemic racism and Black resistance in the US through interviews with the Wilmington 10, their families, and Black Panther Party member Assata Shakur. In a conversation from March 2021 recorded between Haile Gerima and his wife and collaborator Shirikiana reminiscing about Norman, the director recalled Norman’s still photography impressing him enough to ask him to do Wilmington 10’s cinematography. They also remembered Norman being very sensitive in his craft, even at one point starting to cry and leaving the camera while filming an interview with one of the prisoner’s mothers, Shirikiana said “because he was so moved by the way she talked about the incarceration of her son.”

While the NGA series focuses mostly on this DC chapter of Norman’s artistic output, the equally interesting periods before and after have been explored elsewhere as part of a concerted effort over the past five years to increase attention to Norman. Skip Norman: Here and Now series curator Jesse Cumming traces his involvement, for instance, to a screening in Germany in 2018 of Norman’s shorts, which provided, he related in an interview, “an introduction to an artist with incredible political clarity and aesthetic distinction that I had never heard of before.”

This inspired Cumming, who will appear in pre-recorded introductions to the NGA series, to carry out his own research on Norman. He also gives great credit to a number of colleagues in Europe for unearthing Norman’s works from various archives and reconstructing his life trajectory, resulting in a dedicated issue of the Rosa Mercedes online journal and various international showcases, most recently at London’s Open City Documentary Festival in September.

Underlying these efforts is the question of why, given Norman’s own evident cinematic talents and affiliation with iconic filmmakers like Gerima and Berlin classmate Harun Farocki, is his work only now coming to light? Curator Cumming hypothesizes several potential dynamics at play. He notes, first, that Norman largely came of artistic age in Germany and, as a Black expatriate, might not have slotted neatly into either the European or American film movements of the era.