Occasionally, the dancers would congregate at one end of a wooden dinner table placed at center stage to consult a device with a pulsing blue light that sat, Siri-like, on the opposite end. They posed their own questions to it: “Luna: It’s me. Luna: Can you hear me?,” as if seeking directives from their digital oracle, which indeed they were. They were tied to its destiny, as it was tied to their own. Towards the end of the show, a dancer asked, “Luna: What happens next?”

Nearby Luna, a tall vertical lamp hung just above the table and alternated colors and intensities throughout the performance, at times blinding the audience of about 70 people. Other linear and spherical lamps were lit and lowered at different phases of the show.

During one particularly clever vignette, a bright yellow bulb lit up high in the rafters was slowly lowered to the stage. When first apprehended by the dancers, they worshiped this distant star with outstretched arms, as though it were the ancient Sun. As the golden orb made its way to the stage floor, the dancers lay down around it to admire the more humble beauty the Sun permits, that of a flower, perhaps a sunflower.

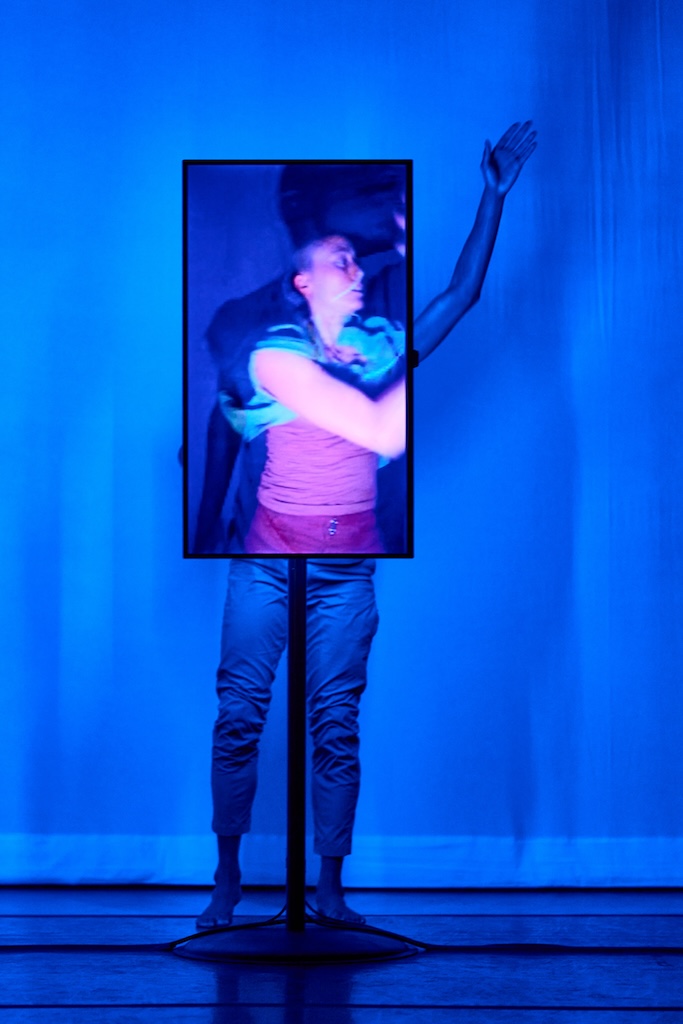

At the rear of the stage stood four flatscreen monitors, vertically oriented like the way we hold our smartphones. The screens displayed pixelated patterns and quasi-abstract imagery that complemented the dancers’ movements. At times, they stood behind these monitors, their bodies’ motions synching up with mimetic visuals appearing on the displays like avant-garde X-rays. The dancers, lamps, screens, and sounds combined into a contemporary version of the gesamtkunstwerk.

At its most unnerving, A&I took on a rather Orwellian aspect. During one of the show’s more disturbing segments, distorted images of blurry-faced, nameless citizens appeared in grayscale on the four screens from a low angle, as if looking down onto the audience. Atonal chords—like those heard in the more discordant tracks by the British electronic musician Aphex Twin—droned on in the background while the dancers’ motions became more mechanical, like robots, making them feel eerily inhuman.

At one point, the monitors showed what appeared to be slow-motion footage of the boosters of a rocketship about to blast off. Just as I was thinking of it, the audio shifted into a creeping organ-sound reminiscent of Philip Glass’s score at the beginning (and end) of Koyaanisquatsi.

Was this homage? Can generative AI make an homage? Or, is it always derivative—quite literally—in the sense that it can only ever respond within the parameters set for it by its human enablers?

In one of the most poignant sequences of A&I, hidden lamps beneath the table lit up for this scene. A camera was also hidden below the table, aimed at the floor whose illuminated surface appeared on the four screens. The dancers, one by one, made their way below the table, embracing one another once there and looking up under the table, as if into the sky, their beaming faces looking out from the monitors at the audience.

The soundscape became layered here with radio transmissions between two astronauts working on a space station in orbit. The banal, operational back-and-forths of the spacemen accompanying the scene beneath the table where the dancers lay engendered a strange sensation, where the space of the theater felt somehow reduced and expanded at the same time. The overall effect was optimistic. It pointed towards a more hopeful future, one in which human beings and their creations might work in tandem to build a better world for all.

* * *