Neo Rauch at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 22 – October 14, 2007

Recently I’ve been listening to the songs of Franz Schubert, the Romantic era composer. His songs are musical excursions into the darker regions of longing and memory, good for indulging Autumn melancholy and, as it turns out, also good preparation for seeing Neo Rauch’s recent painting exhibition, Para, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Schubert’s lyrics were adapted from the works of German Romantic poets, Goethe, Heine, Muller, etc., as well as the casual verse of some of Schubert’s friends. These poetic sources are uneven, ranging from splendid expressiveness to mawkish sentiment, but Schubert’s sheer musical inventiveness fuses these disparate sources into one highly original, dreamlike soundscape.

Neo Rauch frequently cites his own dreamworld as the source for many of his paintings, and numerous critics have spent considerable amounts of time and ink trying to decipher the meaning of his work. A friend of mine who is less-than-enamored with Rauch’s current paintings wryly commented that he “should have better dreams.” Sanford Schwartz, despite a largely enthusiastic overview of Rauch’s work in his New York Review article of September 27, did acknowledge that the crowded, ambiguous imagery of the recent works feels “portentous” and overproduced.

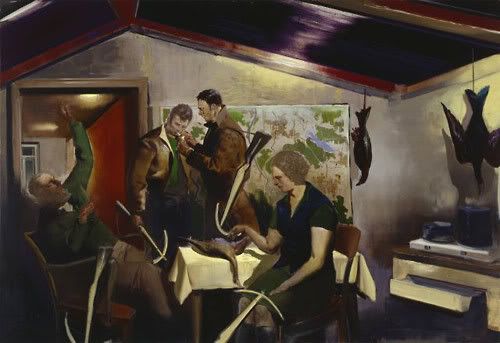

For all of the in-the-moment vibe that attends it, Rauch’s imagery, like Schubert’s lyrics, contains more than its share of wan melodrama and kitsch. Contemporary figures frequently interact with stock Romantic characters, such as huntsmen, robust frauen, field hands, and dandies in period waistcoats, cravats, and breeches. Occasionally these figures are arranged in pocket tableau that allude to, or quote from, the work of numerous painters, including Courbet, Manet, even Balthus. These figurative dramas slipstream into and out of settings that cobble together the modern suburban subdivision and elements of picturesque Northern European landscape and architecture. The cumulative effect of this build-up is often more schmaltzy than dreamlike, like a parade of curious characters shuttling in and out of a bizarre, homemade cuckoo clock. Any attempt to puzzle out specific meanings in these paintings ends abruptly with the realization that Rauch’s dreaming, like any dreamlife, is probably wildly, inscrutably varied, ranging from powerful, but ever-elusive insights and anxieties to charming, fleeting trifles, and the artist is apparently willing to let this unevenness communicate directly into his work unedited. So the pursuit of meaning in these paintings becomes as futile an exercise as trying to find out what time it is in the Twilight Zone.

What brought me back to the Para exhibit for a second look, however, wasn’t any nagging desire to fit the pieces of Rauch’s imagery into a coherent personal or public message. What brought me back were memories of color and painterly applications so vivid that they remained lodged in the mind’s eye like a tune stuck in the subliminal ear.

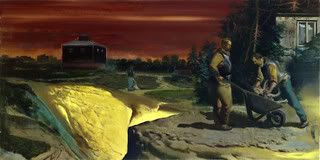

The scarlet jackets on the foreground figures in Para are so lavishly painted that they coat their owners like luxurious plumage, making these figures such a purely sensual presence that we can largely ignore the unanswerable question of what they’re up to in the painting. The expanse of bruised, queasy sky which occupies nearly a third of Warten auf die Barbaren/ Waiting for the Barbarian is likewise memorable for the particularly laden weightiness of its blue which arrests and disquiets the eye. This formidable passage is just so devilishly blue in its own right that it makes the surreal scene it oversees – a courtyard where a Minotaur is being burned at a stake – seem incidental, even trivial, in comparison. The brilliant yellow rupture in the lower middle-left of Goldgrub / Gold Mine bursts like a sumptuous flowering from a field of muted greens and rusted, earthy reds, and does so with such splendor that there is little or no need for the attendant posed laborers and rustic houses a la Millet.

The memory of these painterly passages were, in fact, so strong that they stayed with me for days, long enough and vividly enough that I could work out some of the color shifts and subtleties with trial parches of paint in my own studio. Rauch uses Brown Madder, for instance, to ‘bruise’ or to soften cobalt blue, and to blunt or to enrich his frequent reds.

Franz Schubert managed to smooth out the rough spots of his lyric content with his musical gifts. Unfortunately, Neo Rauch’s painterly riches don’t fully compensate for a visually cluttered and often exasperating content. Many of the works are so packed that the viewer simply can’t squeeze into them, and is forced to be a distant spectator instead of an intimate voyeur. In his New York Review piece Sanford Schwartz remarked that Rauch’s earlier, largely empty landscapes remain the most compelling and promising of his works. This is probably true, because in those considerably sparer works the paint and content can collude in terms of mutual, sheer allure. What initially leads us into a painting is Paint- just as fragrant cooking aromas lead us into the kitchen – and the content, of a painting or a meal, has to sync with the aroused expectations of the senses.

At this point, it is pure painterly skill and bravado caressing the eye, rather than tickling the brain which keeps Rauch from being lumped in with decades of narrative-figure artists who have generally become Painting’s equivalent of the ubiquitous Lounge Singer – artists such as Eric Fischl, Odd Nerdrum, John Currin, or the late Jorg Immendorff (to name just a few) whose guilty pleasures content is always coated in a smooth, sentimental, and formulaic delivery of paint. Rauch’s considerably more present and vital abilities as a Painter could prove the catalytic agent for his next step. In these days when contemporary narrative painting generally amounts to little more than a spectral Karaoke performance of the next New Thing, it is important to recall those few painters who have managed to indulge, and even please, the longings of the sensual eye. The work of Albert York, or the late Gregory Gillespie, for example, serve to remind us that it is indeed possible to accomplish what Neo Rauch apparently struggles to do: fuse an odd assortment of personal tics, investigations and tangents, and inventive, even delirious, use of paint into a diverse and remarkable body of work.

Don Cook