An Interview with Jascha Owens

Dominic Terlizzi is a Maryland native and currently lives, teaches, and works in Baltimore. He received an MFA from Hoffberger School of Painting MICA 2008 and a BFA from The Cooper Union NYC 2003. His work has been exhibited in Baltimore, NYC, London, Washington, Delaware, and Mars.

He teaches at MICA, Towson University, and PI Art NYC. He has taught and lectured in Cebu City Philippines, Seoul South Korea, Jeju Island South Korea, and Beijing China. He received the Maryland Artist Equity Grant, Hoffberger School of Painting Award, Triangle Workshop Fellowship, and the PNC Transformative Art Project Grant. His monumental sculpture with the Remington Baltimore neighborhood, Seawall, and Gensler will be unveiled Jan 2014.

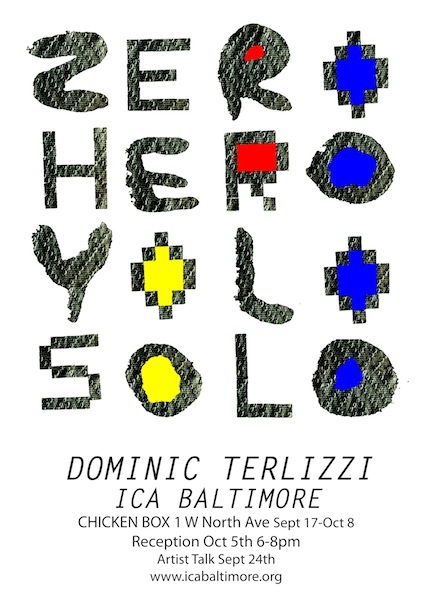

This interview was conducted by Baltimore-based painter Jascha Owens, after Terlizzi’s exhibit, Zero Hero Yolo Solo, opened at the Baltimore Chicken Box.

Jascha Owens: Who are you? What are you doing?

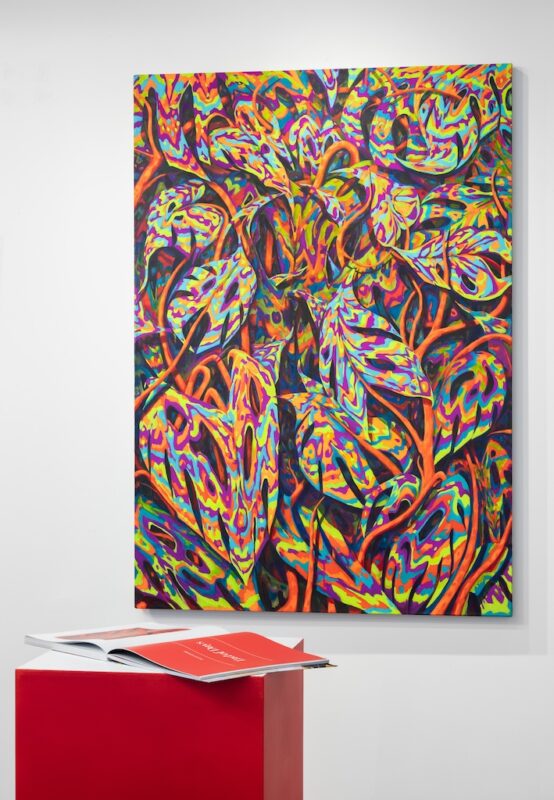

Dominic Terlizzi: My name is Dominic Terlizzi. I graduated from Cooper 03’ and Hoffberger 08’. I am currently exploring a molded acrylic painting process. I create molds of small objects I collect in my travels and then cast acrylic paint with various chromatic color combinations. This allows me to paint with logic beyond a singular brushed application. My process isolates color mixing, and the application in a single mold. Once the paint is cast I can arrange and cut my paint to assemble incremental aesthetics like a mosaic or quilt would.

JO: You grew up on a farm and have cited that as an important factor that has shaped your work. What did you do on the farm? How have those experiences infiltrated your current practice?

DT: I grew up on a farm in Carroll County Maryland. My earliest memories there involved building my parents house with post and lintel construction. I was too young to be helpful but remember being in the way. The farm is still operational and has various crops including corn and soybean. What makes it a unique agricultural operation is the diversity of efforts my grandfather branched out into including Christmas trees and aquaculture which was a way of growing fish in our pond and in above ground tanks. The tree farm was operational during my formidable years. I fondly recall spending days with my entire family planting trees that took years to mature.

The time and work ethic needed to yield results was really humbling from my earliest memories. Recently my parents have begun a vineyard on the farm and it too has taken years to develop. I remember planting the vines while in grad school 8 years ago. We just had our first harvest this fall. In the time it took for vines to bear decent fruit I have also been trying to yield results with efforts in my studio. It’s really funny to think of it that way, but it’s true.

JO: What about labor? I found your discussion of being ‘laborer’ versus ‘painter’ very intriguing and ties into the work ethic of farming. Could you explain this distinction and why it’s important do you?

DT: In my artist talk I tried to explain the process of creating a work with my mold technique. I was alarmed how many times I had to correct the audience that the work was only made of acrylic on canvas and that is all. To define the process and clarify the medium I needed to explain the amount of labor needed to transform a small found object into paint. This means there are many unglamorous days of making molds and then mixing paint to fill the molds.

Hours can pass simply mixing primary colors into secondary and tertiary combinations to fill molds. After all the work leading up to filling molds it still takes 3-5 days for a molded paint object to dry. Once dry, I peel the objects out and trim them up. When I have accumulated a large vocabulary of objects and colors I then can begin to arrange and adhere them to a surface. This process of arrangement or image making only happens on the shoulders of my previous labor in casting.

Since there are two different ways of thinking about making the same product it is as though two different people work on it. I assign myself a role for the day. I am either the laborer or the arranger. As the laborer I feel I need a punch in clock for the day expecting the same hours I would work at any other job.

I often ask myself why is it that I was able to work hard jobs for minimal pay over the years but now that I have studio time it is harder to ask the same hours of myself. I think it comes down to the unquantifiable strain of intuitive emotional responses to a medium and the weight of decision-making when you are the aesthetic arranger. When I am a full time aesthetic arranger I have found my instinct is to eventually destroy my own efforts. Thank goodness I have made friends with the Laborer side of myself.

JO: You just put up “Zero Hero Yolo Solo” at Chicken Box, comprised of a group of paintings using an acrylic casting technique you developed. Did this body come together because of Chicken Box or for another reason?

DT: I really wish I could say I make works for solo exhibitions on the horizon but in truth opportunities are somewhat scarce for exhibiting. I make my work because I need to. That means like most artists who keep making and pay it forward, I keep faith my works will see the light at some point. It was only once I had a chance to exhibit this recent series that I truly realized how important white wall ‘painter’ friendly venues are for Baltimore. I need to give credit to the ICA for seeking me out and valuing my works in a current dialogue they are trying to create within Baltimore. I also think the Chicken Box was a perfect venue for what we were trying to do with the paintings.

JO: Could you describe how these paintings are made and what led you there?

DT: When I was at Hoffberger, I set up a still life with toys from my childhood as a way to rile up something unknown yet familiar. I began making encampments for my armies of toys and I used snack foods in my studio. Once I realized how interesting the cracker architecture was I abandoned the figurative toys. I later abandoned the ready-made breads and introduced my family’s dough recipe to make figurative characters. With each exploration I realized the failures and over reacted to solving their down fall. My biggest failures involved preserving bread narratives in bronze.

Having created entirely monotone bronze textural reliefs I longed for color and high chroma combinations with textures. I also knew that the unapologetic ramblings of my childish mind preserved in bronze became cumbersome and limited the elevation of some of the most profound parts. I set out to invent a method that would unify the best parts of all my experiments over the past 8 years. The solution was to create a vocabulary of molds and access incrementally assembled color fields.

JO: What kind of reactions have you received to the show and the work? Anything surprising, discouraging, and or inspiring?

DT: Here is our surprising story: A couple wandered in off the street not knowing it was an art show and could not understand exactly how the work existed. They asked me questions for ten minutes just trying to realize it was painted. They had many cultural associations way beyond my influences like Caribbean fabrics and African colors. They loved the craftsmanship and wanted to purchase one. When reviewing the price list the woman asked why everyday discarded objects she already knows about would cost so much in a painting and her husband said, “Honey imagine all the labor it took for him to make these!” I thought that was a fascinating discussion and one that proved to me I was succeeding in my effort to create paintings which allowed access for many other cultural and social spaces while questioning the values of visual language, my labor, and aesthetic arrangement.

Another interesting interaction over the paintings happened during the opening. I met a woman who adored the paintings and also wanted something to eat. I had made pretzels and homemade beer for all my guests at the show but she was unable to handle hard foods. So instead I took her to a meal at McDonalds during my opening just to keep chatting about the work with her.

Here is our inspiring story: I have never seen such a diverse crowd of individuals from various backgrounds in the same exhibition space to question and enjoy paintings. I was extra pleased to see so much of Baltimore show up.

JO: One response I had was to look at the work in the light of reactionaries to abstract expressionism such as Jack Whitten. There’s this air of free flowing composition and movement yet the material, the paint, remains solid and grounded like a stack of bricks. You aren’t flinging paint like Pollock, or pouring or even painting! You are collaging, cutting and gluing, which is a very mediated process and removes your hand from marking in a way. Was this part of your intension? Are you thinking about people like Whitten or Olitski who questioned the basic mixture of pigment suspended in medium applied with brushes?

DT: You are correct. I have made decisions in the process of the work to remove my direct hand or brush work. Yet I want to feel there is an autonomous energy in how the paintings gather themselves. There is logic in how incremental shapes fit together that forces a slower assembly. This makes it impossible for me to foresee each future move. Maybe this is embracing the unknown or my own ignorance about the works trajectory. There definitely is nostalgia for American Abstraction in my recent work. I never really considered Whitten an influence until I began aligning my process with his. I also find that his politics are possibly different than mine yet we are striving for similar territory. I have gotten many other references about the work including Alfred Jenson, Gees Bend, and Mosaics.

JO: Do you have ideas about where the work is headed next? Will you continue to use this casting process?

DT: I have begun to select objects to begin creating new molds. I’d like to start taking chances with the way things get constructed. In the recent show I used strict rules just to learn about this new process and build a language. Now that I know a little bit about what is possible I’d like to challenge my approach. It could be interesting to see how brushing or marking directly could reenter the image.

JO: Something I’ve always admired about you is the way you embrace Baltimore. You have worked on projects all over the city and are constantly seeking engagement with the local community. I see you as a kind of Dan Deacon in Baltimore’s painting world. Could you talk about this city a bit? How it’s influenced you and how you’ve responded?

DT: I grew up around Baltimore. I first began visiting Baltimore when I was 16 years old. That was 17 years ago. I would head to fells point with some friends and play guitars in the street acting like kids. It was way before anything really developing with arts here for me. I moved to NYC at 18 to attend Cooper Union then return to Baltimore when I was 22. I worked in Hampden on Bronze monuments at New Arts Foundry. For lunch I would go to Dizzy Izzy’s sometimes and also attend Angel Falls Studios for openings after work for some months. Angel Falls Studios became Charm City Cakes.

I really came to understand Remington Baltimore as an unknown place with possibilities. I bought a house in Remington before I attended grad school thinking I’d like to stick around or have a home base between east coast cities. Since joining the Remington neighborhood, I have taken part in as much as I can here while maintaining a studio. I helped start Hautingdon, participated in GRIA, painted several murals, partnered with Seawall and created several projects for MICA students here. I think feeling like my skill set is bettering the environment around me is irreplaceable. By asking how my skills can allow access for others in Remington in turn questions what the role of my studio paintings have. Baltimore is very present in my recent paintings because many of the objects cast had been collected from the street. This is a city full of detritus and interesting traces of others.

JO: You have a big project coming to fruition soon. How did the Remington “R” public sculpture happen? What stage is it in right now?

DT: I am very excited about the Remington R. The story of the R begins during the winter session 2013. Last winter was an intense time. Before leaving to teach a winter session in Korea I also took on a quick winter session class with David Humphrey. He was visiting to co teach an opera class at MICA. It was an interesting course in which I hand picked students with various skill sets to make backdrops and props for an opera he envisioned about Walt Disney.

After a few weeks of working on the opera I traveled to the southern island of Jeju in South Korea to teach painting for PI art center. I thought I was balancing enough already but I received a phone call in the middle of the night on the island from the President of GRIA. I was informed that Remington had a unique opportunity to create a transformative sculpture by partnering with Seawall. The problem was a fast approaching deadline. Consequently I downloaded Google sketch up and began drafting models of Baltimore while in Korea.

When I returned to the States I immediately met with a committee and sculpted 15 maquettes. In truth, the board all voted and decided which sculpture would work best on the site. We made a compelling application and won the grant from BOPA. The result is a 30-foot aluminum structure to be installed on the corner of 26th and Howard. Currently New Arts Foundry in Hampden is assembling the sculpture.

JO: What has it been like to work on a project of this scale – both literally and figuratively?

DT: It has been a learning experience. How often does an artist have a 30-foot sculpture installed in their neighborhood? It is so complicated working with a committee because everyone has a stake in the project and a slightly different vision. It is terribly difficult to balance all the interests of the community and the developer at once but I think we are doing it. I also think it has made me try to be more assertive about the value of an artist working on behalf of a community space.

I am working for the sake of the community and in the interest of a sculptural opportunity. I find it hard to understand why a small minority of community members have been negatively outspoken about the project. I think it mostly deals with confusion about what the project is, what the money is for, and where the money is going. For someone who has a hard time making ends meet in Remington 30k going to a project seems like way too much.

If not for the PNC transformative grant with BOPA we would have no funding arriving for sculpture or any other dream efforts here. I have worked pro-bono and have argued to use as much of the funds as possible to enable the most elaborate and destination setting sculpture. It is alarming how quickly a budget evaporates when you are trying to build something large.

The conflict for many is about a community’s priorities. Many would like to see money go to schools, or to clean up drug use. What I think may be misunderstood about sculpture in communal spaces is that it will encourage pedestrian traffic reducing the likelihood of drugs and trash. This will make the community more family friendly. To place art at a major intersection of the community announces to the city that we value culture, and also have a unified community even if it can feel divided by a few members. There are many logistical things left to figure out but I have faith it will come together smoothly. I imagine pirate jokes may follow the installation.

JO: What advice could you give to artists pursing public oriented projects in Baltimore?

DT: Make your own opportunities. Hold yourself to the standard of professionalism you’d expect of others regardless of the city or presumed audience. The world is watching anything noteworthy including things in Baltimore city. Also, no good deed goes unpunished. When you get punished, don’t stay on the bitter bus too long or you will forget where you were heading.

JO: Are there other projects, ideas, or happening you’d like to mention?

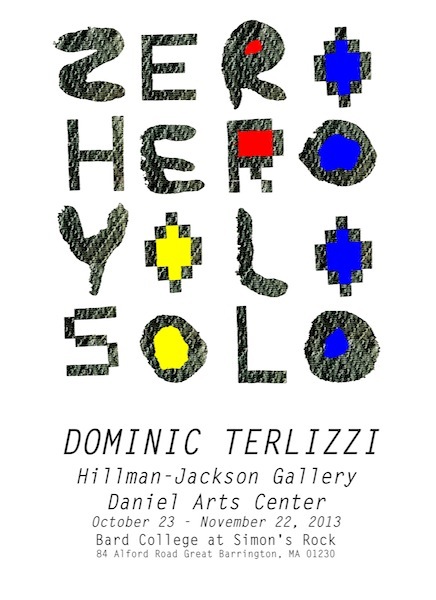

DT: I just installed a solo exhibition at Bard College. I encourage anyone in the Hudson area to journey over the Mass line to see the work. It is based on the solo exhibition presented by the ICA Baltimore spotted by Alan Reid. The Bard exhibition includes 7 new works.

Zero Hero Yolo Solo

October 23 – November 22, 2013

Hillman-Jackson Gallery

Daniel Arts Center

Bard College at Simon’s Rock

84 Alford Road

Great Barrington, MA

www.simons-rock.edu

www.dominicterlizzi.com

*Author Jascha Owens is a Baltimore-based painter and a recent MFA graduate of MICA’s LeRoy E. Hoffberger School of Painting.