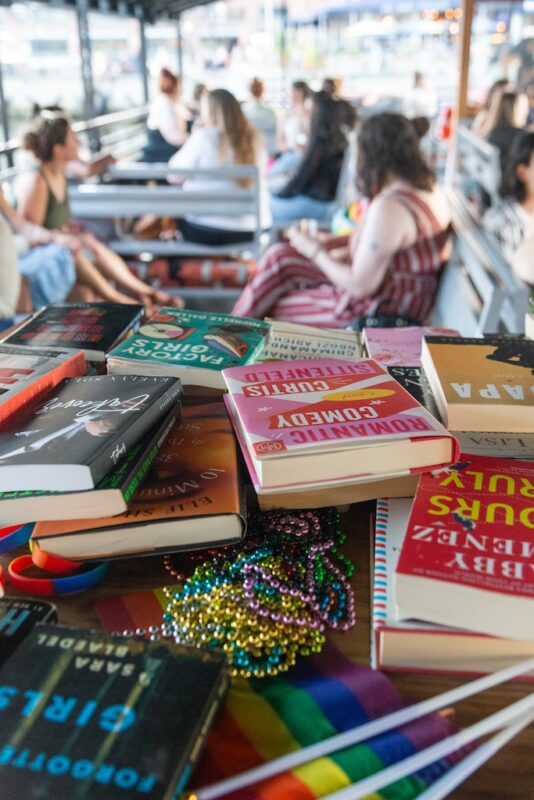

Irena Stein’s debut cookbook Arepa: Classic & Contemporary Recipes for Venezuela’s Daily Bread, released in July of this year, has already garnered massive attention. “I think it’s because of the migration and the level of migration. Eight million people is not a couple of people,” she says about the last ten years of refugees and migrants leaving Venezuela. “It’s a lotttt of people,” she says, stretching the word for emphasis.

According to the UN Refugee Agency, 7.7 million Venezuelans have fled the country due to political instability and extreme poverty. Many people leaving their native land do so on foot, walking days to neighboring countries. Migrant organizations have multiplied over the last five years to aid in the Venezuelan diaspora, including material assistance and psychosocial support. A majority of these organizations are based in Colombia, Latin America, and the Caribbean. If Venezuelan migrants do eventually come as far as the US, they are often met with hostility. “Everybody thinks that every Latina is illegal, so for me, the fight to talk about the contribution that we give to our city and to this country—all of that has to be shown with tremendous beauty,” Stein shares. Her book is dedicated to the migrants of Venezuela and it is a work of tremendous beauty.

Over 50 recipes, developed in collaboration with Venezuelan chef Eduardo Egui showcase the Venezuelan staple in all its forms. The traditional corn arepa, neutral in flavor, is a vessel for endless variations. Savory stuffed La Rumbera with Roast Pork and Gouda and Sweet Coconut Arepas served with Prawn Curry demonstrate the versatility of the white cornbread. Beyond the arepa, supplemental recipes from David Zamudio, executive chef of Alma Cocina Latina Restaurant, make the cookbook a corpus on the anatomy of Venezuelan cuisine.

The cookbook traces the journey of the indigenous corn patty and cuisine through 500 years of colonization, independence, and migration. Each richly colored photograph was captured by Stein and the book showcases her travel photography while visiting her birth country, including places and people of her culture. Since 2016, Stein has had to travel to and from Venezuela without her US-born family, due to increasing sanctions on the poor country. “Venezuela is gorgeous but for now, you cannot go,” she says swiftly with a multi-lingual swagger.

Born and raised in Venezuela, Stein also lived in Paris and Belgium during her childhood. She attended university in Brussels before she returned to Caracas to work with underserved youth. “My last [job] in Venezuela was to develop cultural activities in the seventeen public libraries in Caracas,” she shares. She helped to create youth centers and activities for underserved communities in “shanty towns” or barrios of the Venezuelan capital.

“When you walk through [a poor community] people are watching you and watching for you as well. You have your support system watching you for safety, especially after hours,” she explains of the informal care system built into the fabric of Venezuelan culture.

“When my mom was very, very old she would still go with her cane. She died at 98, and she was a badass the whole way through,” Stein shares proudly. As her mother aged, the communal care for her became more visible. Irena shares, “All the [shopkeepers] would watch my mom to make sure that she wouldn’t fall. Down the block [they would] come out and watch. There’s this code of safety.”

What Stein calls a “code of safety” is often referred to in philosophy as an “ethics of care.” Philosophers Joan Tronto and Bernice Fisher define care as “a species of activity that includes everything we do to maintain, contain, and repair our world so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, ourselves and our environment.” This feminist approach to ethics is a theme that runs throughout Stein’s life, influenced by her mother but also by the culture of care and safety in Venezuela.

Stein shares that her mother was very culturally devoted. Always pushing her to learn more, she told her, “You have to be great. You have to give back to your country. You’re gonna end up in your country.”

Though Stein did not move back to Caracas, she did open the Venezuelan-centric Alma Cocina: Latina Restaurant in 2015. The restaurant moved from its original Canton location to Station North in 2020. Between Caracas and Baltimore, Stein says there are similarities in the disproportion of the wealthy and underserved communities. “It’s one of the reasons I moved here.”

Relocating from San Francisco twenty-five years ago, she shares that the money in Silicon Valley was unrealistic in proportion to her life as an artist. Irena was making $25k a year as a jeweler while many young tech workers were making a quarter of a million or more. “I didn’t want my daughter to think that this was the world,” she says.

Stein studied cities from North Carolina to Philadelphia and Baltimore. Ultimately she decided on Baltimore for its proximity to other cities. “Baltimore is like Brussels—it’s close to many countries. Baltimore is close to many cities, and Fells Point reminded me so much of the Netherlands and Europe,” she says. Her dreamy perspective of the cobblestoned waterfront paired with a scholarship for her daughter at Park School cemented her decision to leave San Francisco for Baltimore in 1998.

Everybody thinks that every Latina is illegal, so for me, the fight to talk about the contribution that we give to our city and to this country—all of that has to be shown with tremendous beauty.

A few years later, Stein made the leap from jeweler to pastry chef at Gertrude’s before opening her own restaurant, Azafrán, on Johns Hopkins Homewood campus. Stein’s food sourcing has always been centered around sustainability. “We have a lot of tropical ingredients [at Alma Cocina Latina], so in that sense, we don’t support the local economy… We have coconut and passionfruit and things that definitely don’t grow here,” she explains. But when it comes to the sourcing, it has to be done with care for the environment. “All our food, especially the protein, is sustainably sourced.”

While many ingredients of Alma Cocina Latina’s cuisine are tropical, Stein sources local ingredients whenever possible and maintains a commitment to the environment and to local organizations supporting like-minded causes. All glass bottles go to GRASS Baltimore, “Glass Recovery and Sustainable Systems,” a zero-waste artist cooperative. Alma Cocina Latina and Foraged, the neighboring hyper-local restaurant, collectively compost.

Alongside a commitment to sustainability, Stein is focused on being an advocate for migration.

“We have nine nationalities in Alma. Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Honduras, Nicaragua, Japan, and more,” she says. “Migration is super important, but just to take care of my own people’s [Alma Cocina Latina workers] immigration status is a lot.” Stein coordinates the lawyers, payments, and travel for migrant workers coming into the US to work at Alma Cocina Latina. She and her husband Mark offer the third floor of their home to them. “The ones that were sponsoring, we’re paying for them and they pay us back slowly. We also welcome them in our house so they have a few months where they can save money with their salaries,” she says.

Venezuelan chef Fernando Bertelsen, who currently lives in Madrid, will migrate to Baltimore on a J-1 visa this fall, ahead of the opening of Candela. The newly envisioned arepa restaurant will be located around the corner from Alma Cocina Latina. Chef Bertelson, who has two months after receiving his visa to arrive in Baltimore, will train under Alma’s chef, Zamudio while Candela wades through the mire of permit delays within the city.

Mark Demshak, Stein’s husband and business partner, shares that they will crowdfund the project on crowdfundbaltimore.com—a local platform scheduled to be live by the end of October. “Instead of Honeycomb, which is a more national thing, we’re going to use this one,” he says. Candela Arepa Bar will be the first project on the platform for the city.

Stein takes me on a tour of Alma Cocina Latina, including through the kitchen where Blanca works on unpacking short ribs from their fourteen-hour sous vide bath. She says she will remove the fat, put something heavy on them, and refrigerate for two hours before she portions and weighs them for service. The short rib is served with guava-achiote sauce, green apple salad, citrus vinaigrette, and white bean-potato purée.

We walk through the lush canopy of indoor plants scattered throughout the dining rooms. “That one is twenty-eight years old, that one is fifty-four years old, and that one is about thirty-eight.” Stein says pointing at the massive potted trees. “They live here. Can you imagine they live here?” She pets the leaves of one of her large living ornaments. Our conversation drifts from the mirrors and thrifted antique decor to Buddishm, meditation, and living a life with purpose. “How do you create dialog intensely with others to abolish your preconceived judgments?” she ponders aloud.

“I love dialogue,” she says. “It’s easy when you and I have so many things in common. That is not so easy when you’re talking about major issues [such as] racism in this city or when you meet people that are not from your culture. What happens then? How does it end? Are you closer [to] understanding their culture? I think that’s my whole job here at Alma. The dialogue,” she offers resolutely.

“And I water the plants,” she adds laughing.

Alma Cocina Latina Restaurant is open seven days a week for dinner and for brunch on Saturday and Sunday. Candela is slated to open this fall. Arepa: Classic & Contemporary Recipes for Venezuela’s Daily Bread is available at bookstores nationwide.