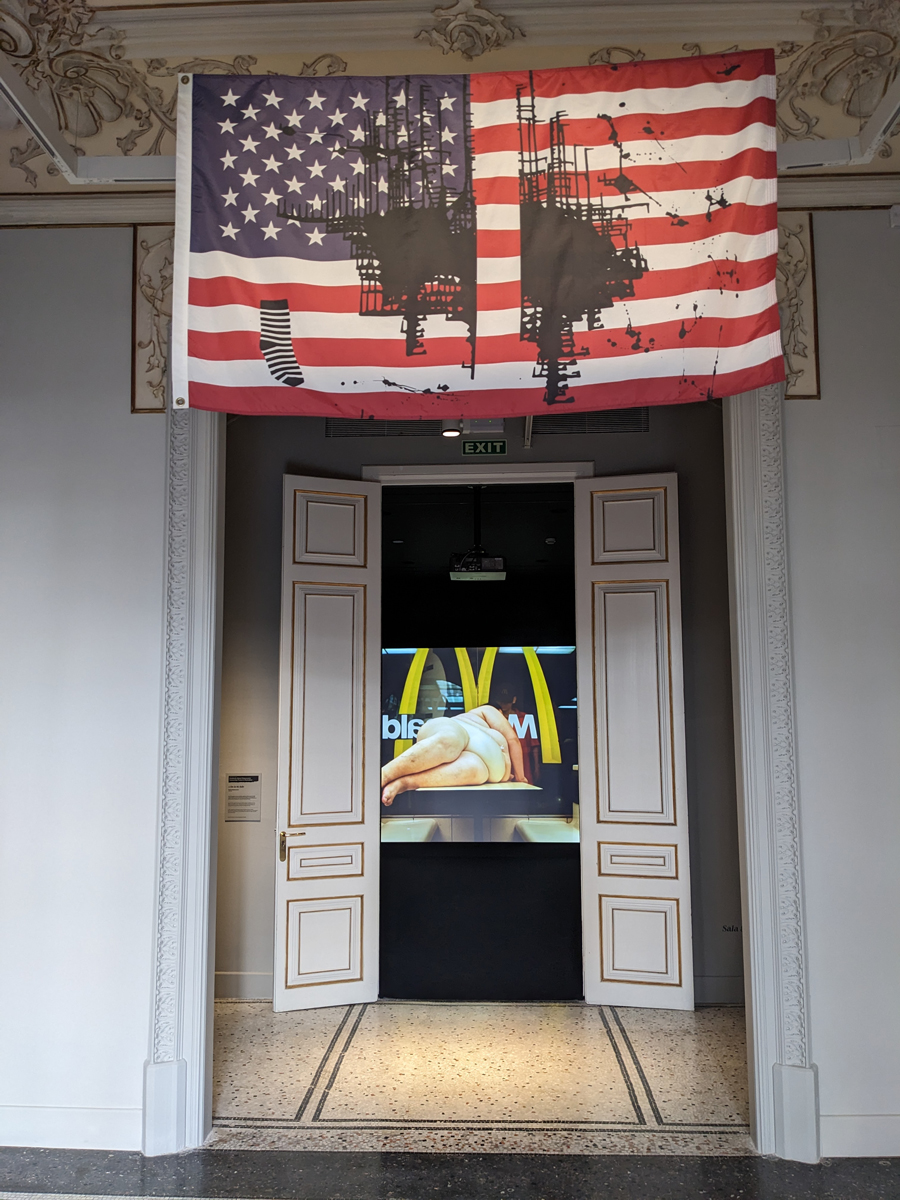

The Museu de l’Art Prohibit is, according to its founders, the first of its kind: a museum dedicated to the collection, preservation, and display of art that has been censored (in one way or another) elsewhere. Its contents are equal-opportunity offenders—having already outraged most of the world’s major religions, every corner of the political spectrum, and ultra-nationalists both here in Spain as well as locales ranging from Japan to Mexico, to name a few.

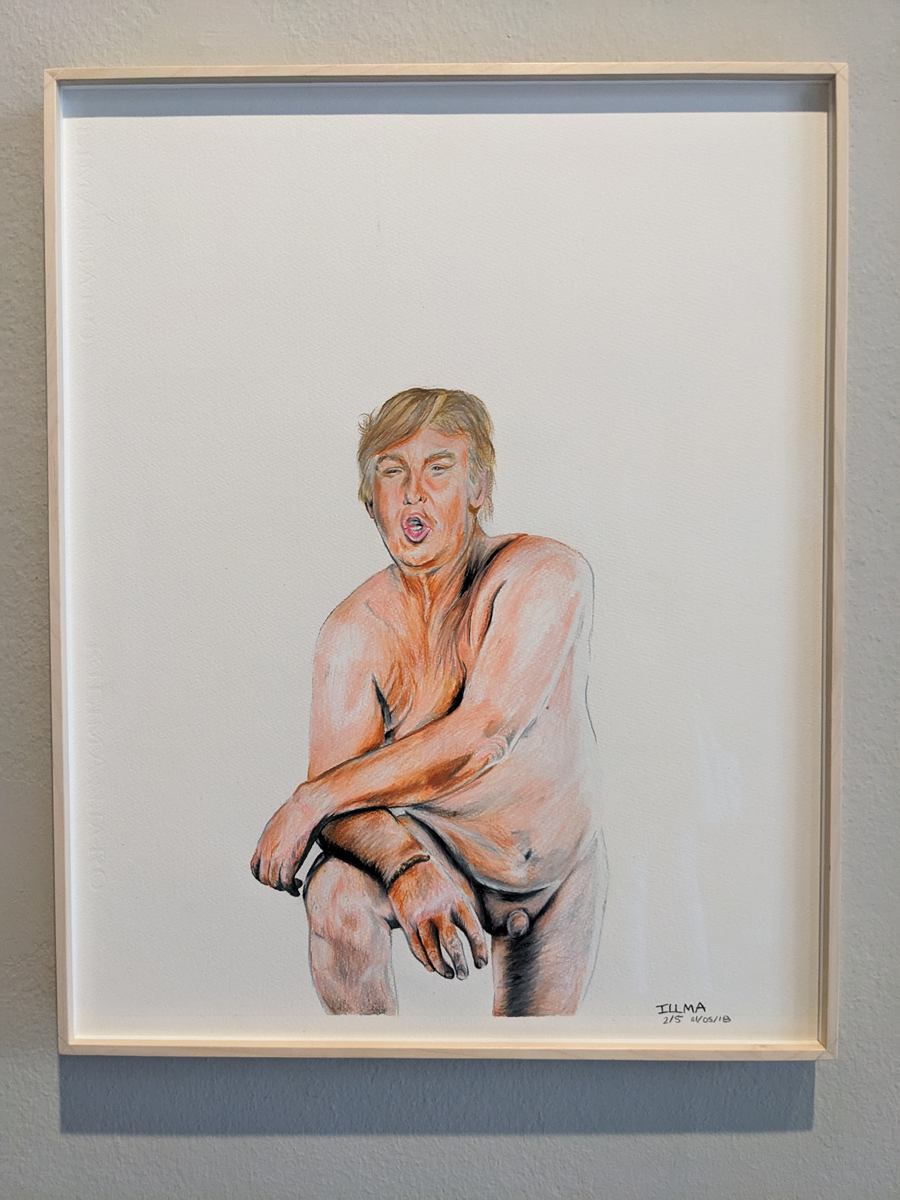

The museum is the brainchild of journalist Tatxo Benet, who became alarmed at the resurgence of censorship in the art world at the opening of the 2018 edition of the ARCO fair in Madrid. He had just purchased the series Presos políticos en la España contemporánea by the controversial artist Santiago Sierra, and wanted to show his recent acquisition to his friends. But when he returned to gallerist Helga de Alvear’s booth later, he was shocked to find the series had been removed from display. Apparently the president of the convention center authority had requested the gallery take down the portraits of jailed Catalan separatists lest they offend the political sensibilities of an increasingly conservative collecting class in the Spanish capital.

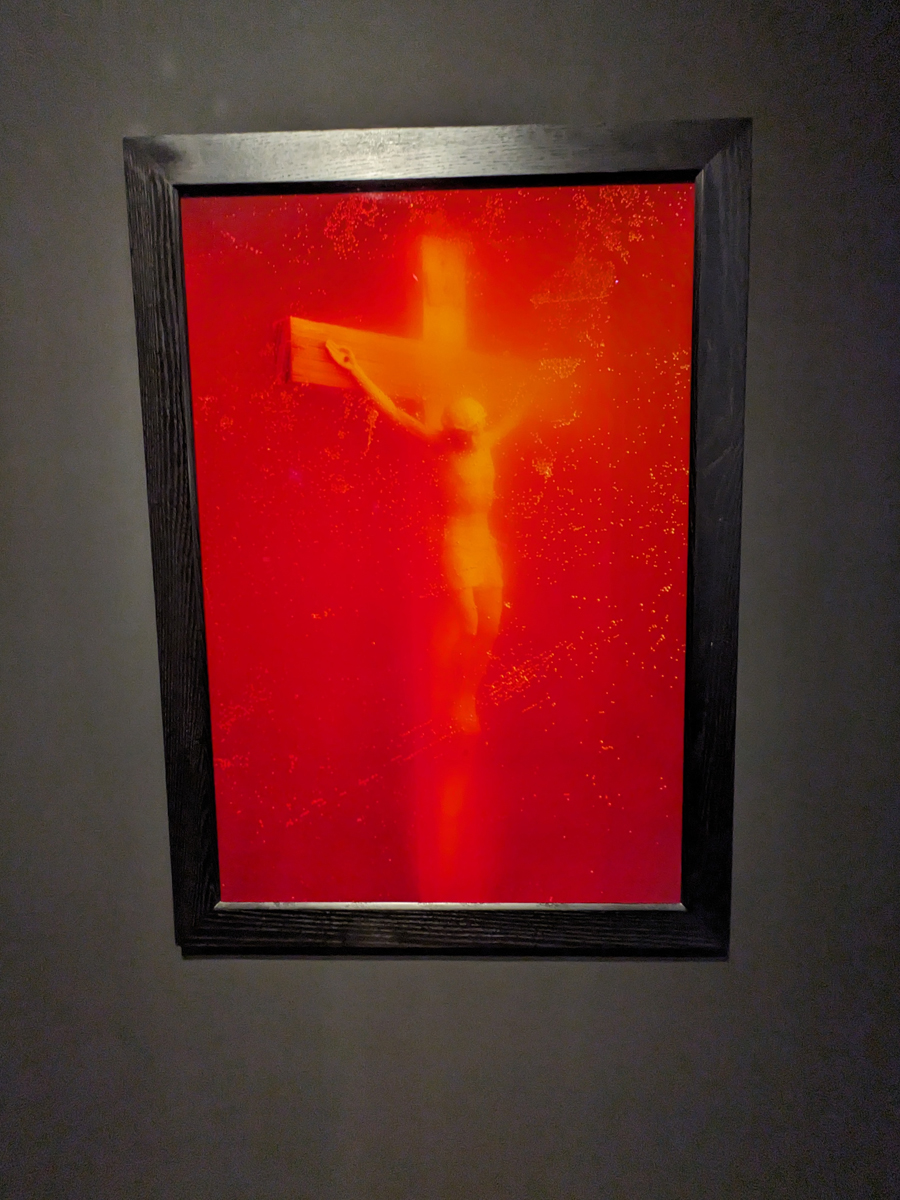

“I started searching online for artworks that had been censored worldwide,” Benet explained at the museum’s press preview, “but I didn’t think ‘oh one day I’ll have this building in Eixample and open a museum.’” The gorgeous setting itself was also important. Designed by Enric Sagnier as a private residence for a wealthy family in the beginning of the 20th century, it was abandoned during Spain’s brutal civil war, a conflict which resulted in the persecution, exile, or extermination of much of Barcelona’s intelligentsia after the city’s reluctant fall to the fascist army. Ironically, it later served as a Catholic school—a fact that made me chuckle while viewing many of the blasphemous artworks it now houses.

It’s also located steps away from the grand avenues where the contemporary right wing had staged massive marches to protest a proposal to grant amnesty to the Catalan separatists just days before. Looking out the window, and remembering those car bomb scares of my youth, I was alarmed to see there was still curbside parking directly in front of the museum. At the reception on the sunny terrace—surrounded by throngs of Catalan anti-fascist politicians, high-profile journalists, and the world’s most controversial artists—I caught myself anxiously scanning the surrounding rooftops for snipers.