I find myself wondering why these seemingly unrelated, powerful works are grouped together and apart from the rest of the exhibition. Then it dawns on me—these are the only exhibition spaces I’ve visited not utterly mobbed by throngs of other visitors. As viewers, my companion and I have the rare biennale privileges of time, personal space, and intimacy to really connect with works that demand those resources.

It’s one of the many curatorial decisions I appreciate the longer I stroll around the Arsenale. It occurs to me Pedrosa and his team take an almost cinematic approach to pacing, storyboarding, and establishing dramatic sightlines. Walk from the intimate, slow-burn installations with time-based components and encounter monumental, sweeping site-specific interventions set against impossibly photogenic backgrounds.

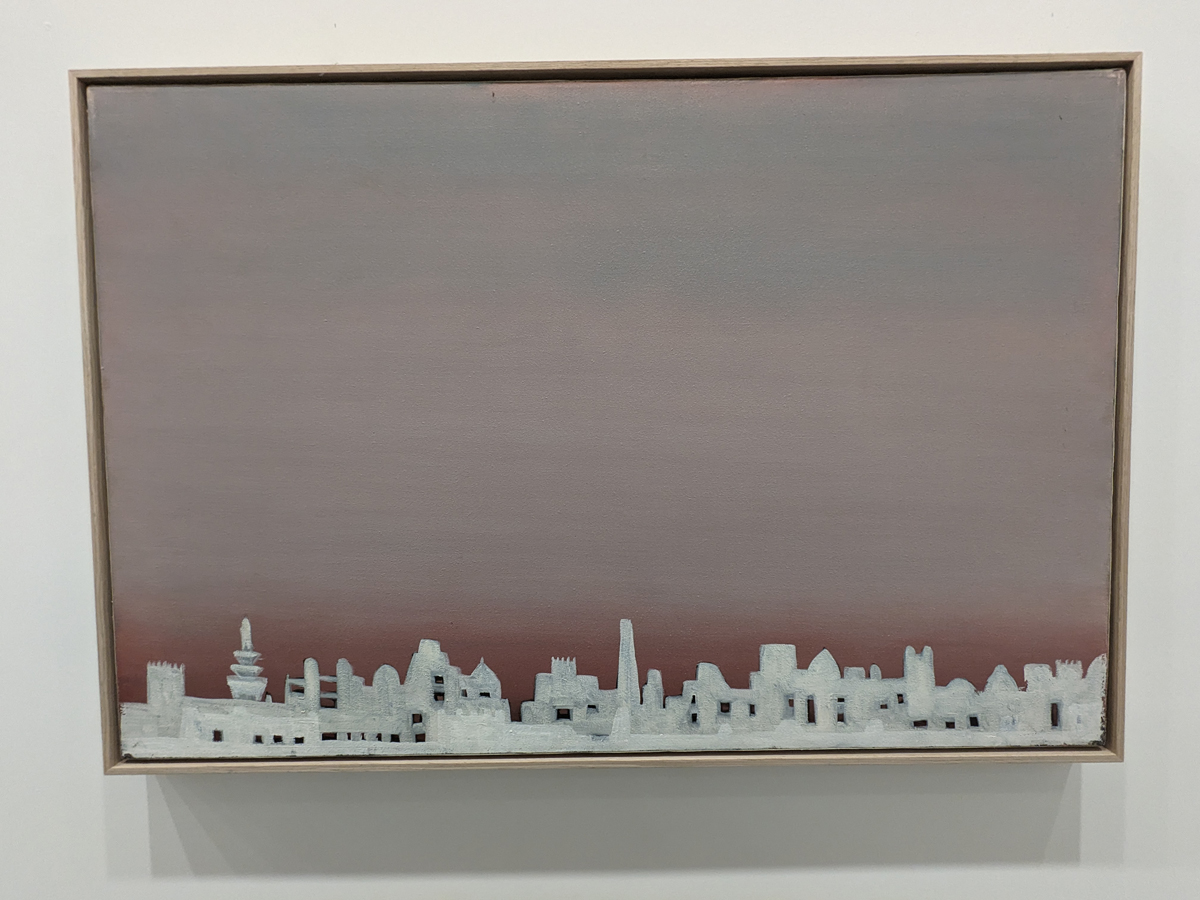

A polylingual flock of Claire Fontaine’s “Foreigners Everywhere” flaps in the breeze, blazing signatures on a postcard cityscape. Turn the corner and Lauren Halsey’s Egyptian-inspired afrofuturistic columns almost seem like they could’ve been there forever. On closer inspection they give the impression of set dressing for a speculative fiction flick I desperately want to watch—one that collapses timelines, geography, and the Mediterranean’s relatively recent function as “moat” separating Europe from the world beyond. They’re future/past ruins reminding us that the sea was historically a permeable site of exchange between the ancient civilizations that bordered it.

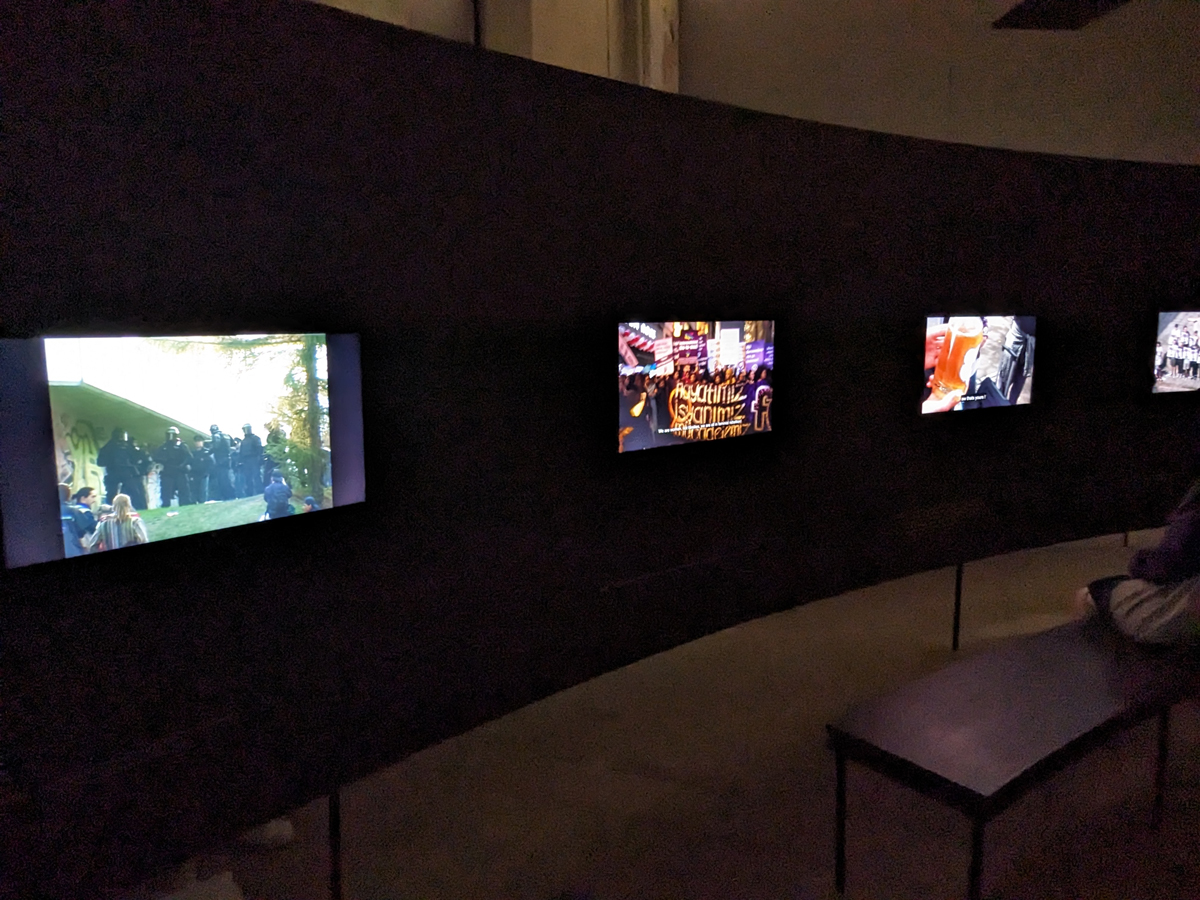

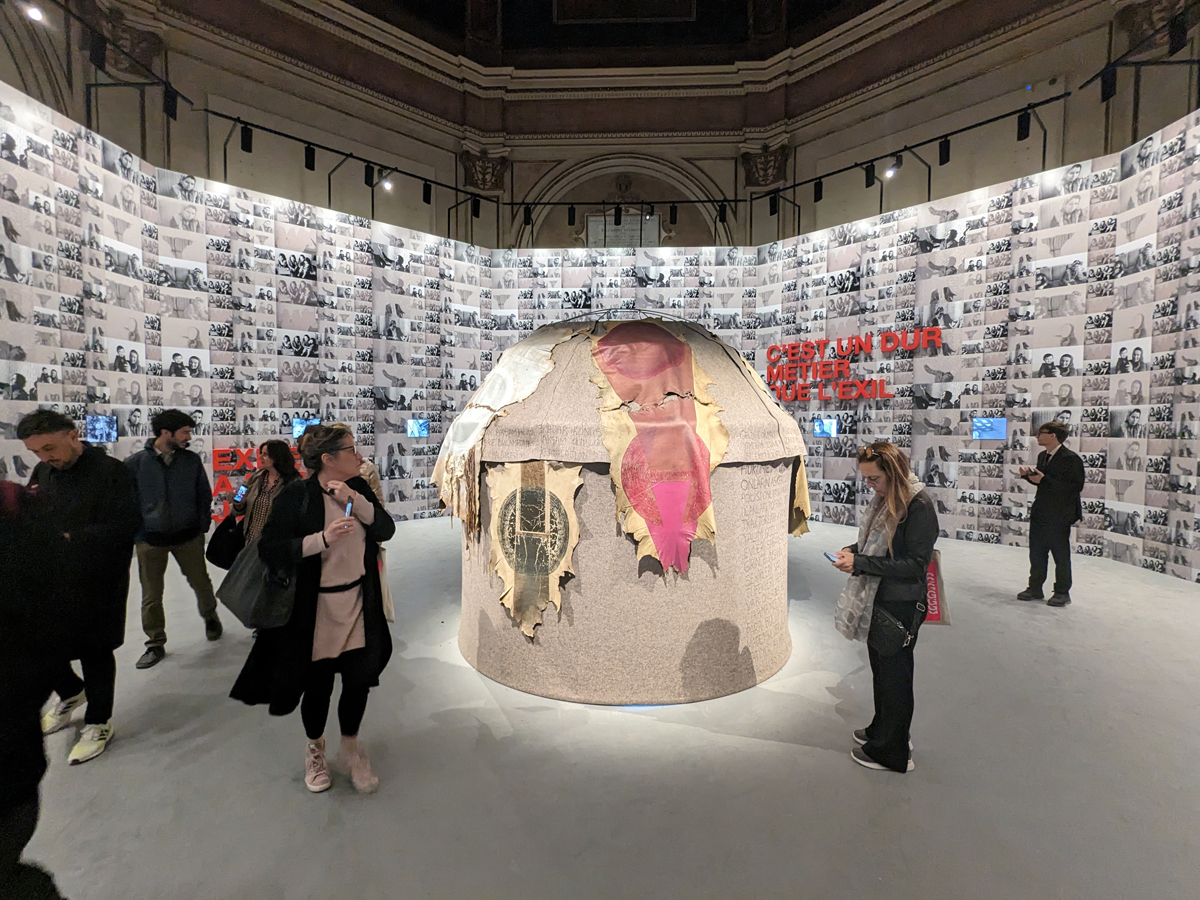

The jump cuts in scale, tone, and focus are perhaps most thrilling within the Arsenale’s hangar-like Corderie. In one claustrophobic chamber, Marco Scotini’s “The Disobedience Archive,” leads viewers through a dark spiral lined with personally-scaled videos of global protest movements.

Suddenly, we emerge into a cavernous bright space dominated by massive textiles and references to the built environment. It’s a climactic rush after the tension of the gallery preceding it.

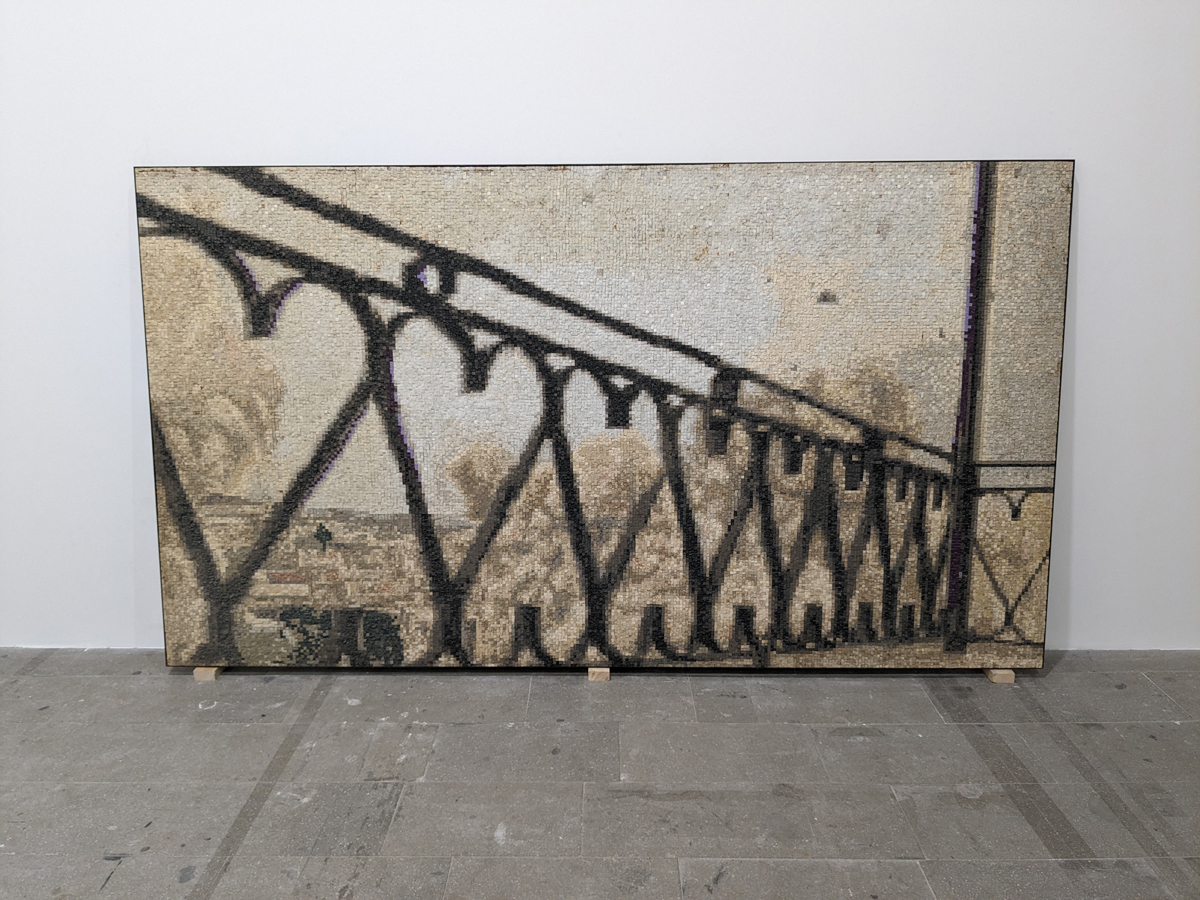

But more importantly, the urgency, collective anger, and occasional optimism of “The Disobedience Archive” sets the conceptual stage for how we interact with the objects in the room that follows it. There are disembodied architectural details relating to real or perceived security concerns, collectively-authored patchwork embroideries whose survival is a testament to resilience, and more moments of synergy across materials, cultures, and practices than I could list without ruining some of the joy of making those connections yourself.