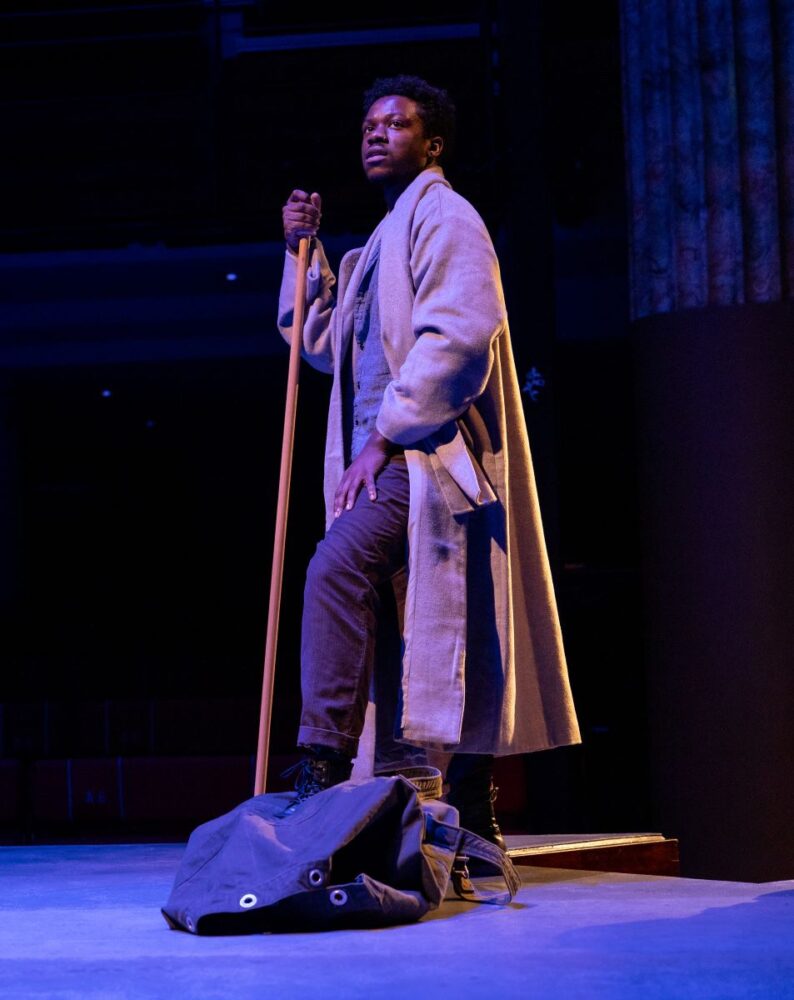

Murder and retaliation come vividly alive in The Oresteia at the Chesapeake Shakespeare Company through March 10. CSC’s current production, an adaption of Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy by Ellen McLaughlin, is brilliantly directed by Lise Bruneau and features outstanding performances by Isabelle Anderson as Clytemnestra and Lizzi Albert as Electra.

The three plays of Aeschylus’ Oresteia present a series of retaliatory killings among the ruling family of Argos. King Agamemnon personally sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia so that his fleet can sail for Troy. Wearily returning after sacking Troy, he is murdered by his understandably resentful wife, Clytemnestra. Ten years later, their son, Orestes, returns from exile, reconnects with his embittered sister Electra, and kills Clytemnestra. For that deed, Orestes is driven out of Argos and hounded across Greece by a squad of Furies. Orestes eventually makes his way to Athens, where he appeals to Athena for relief.

McLaughlin’s version compresses Aeschylus’ three plays into one. She cut four characters, much dialogue, and all of the choral songs that the Greek audiences loved. McLaughlin’s main structural revision was to combine all three of Aeschylus’ choruses—each play had its own—into a single group, the servants in the royal palace.

Using a single chorus allows McLaughlin to end the separation of the chorus and the leads which was so important to the Greeks. In her version, the main characters move among and speak to the chorus members as individuals and they reply in kind. The result is that the chorus become members of the cast. They give the audience the backstory; they also grouse and bicker and undercut the lofty speeches of the leads. After Clytemnestra recounts a dream that fills her with foreboding, one of the maids (Hana Clarice) grumbles, “Why do I have to listen to everyone’s nightmares?”