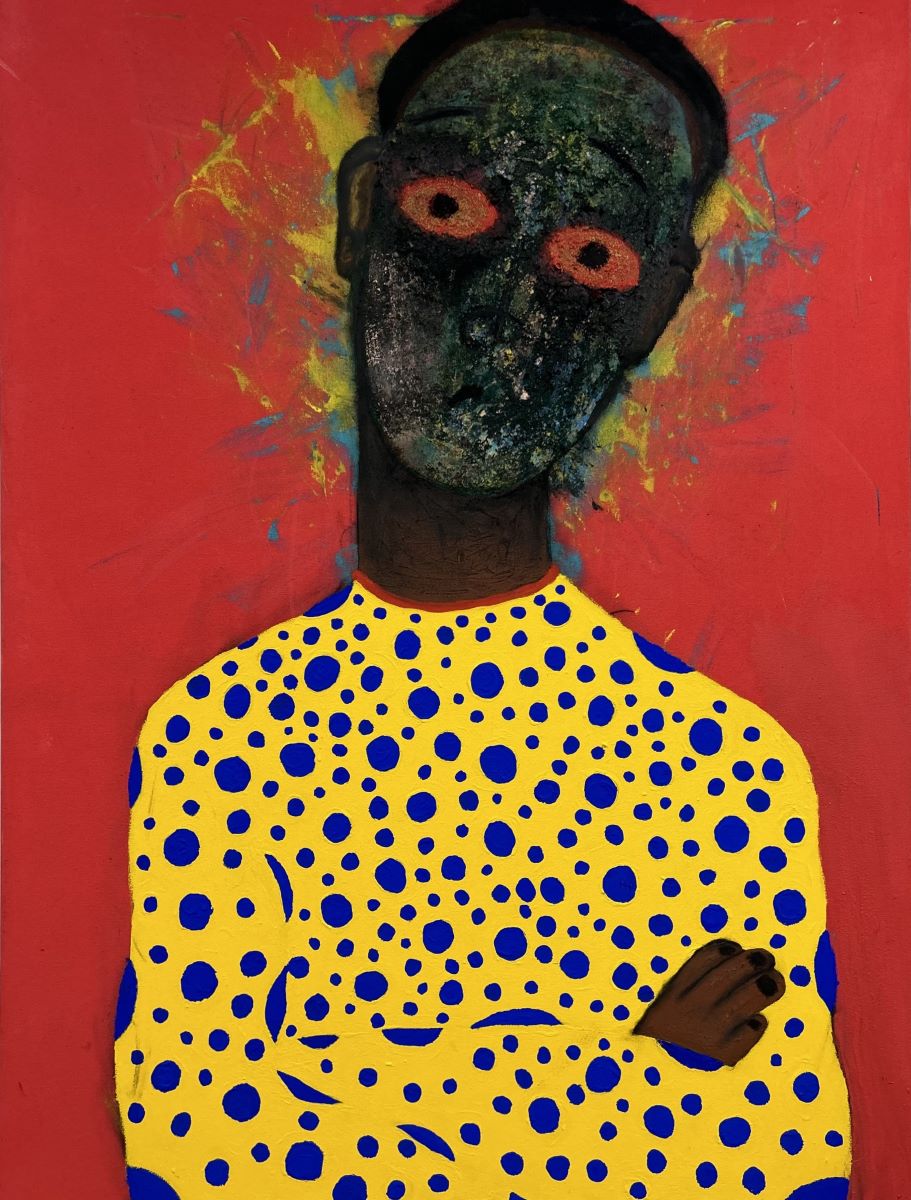

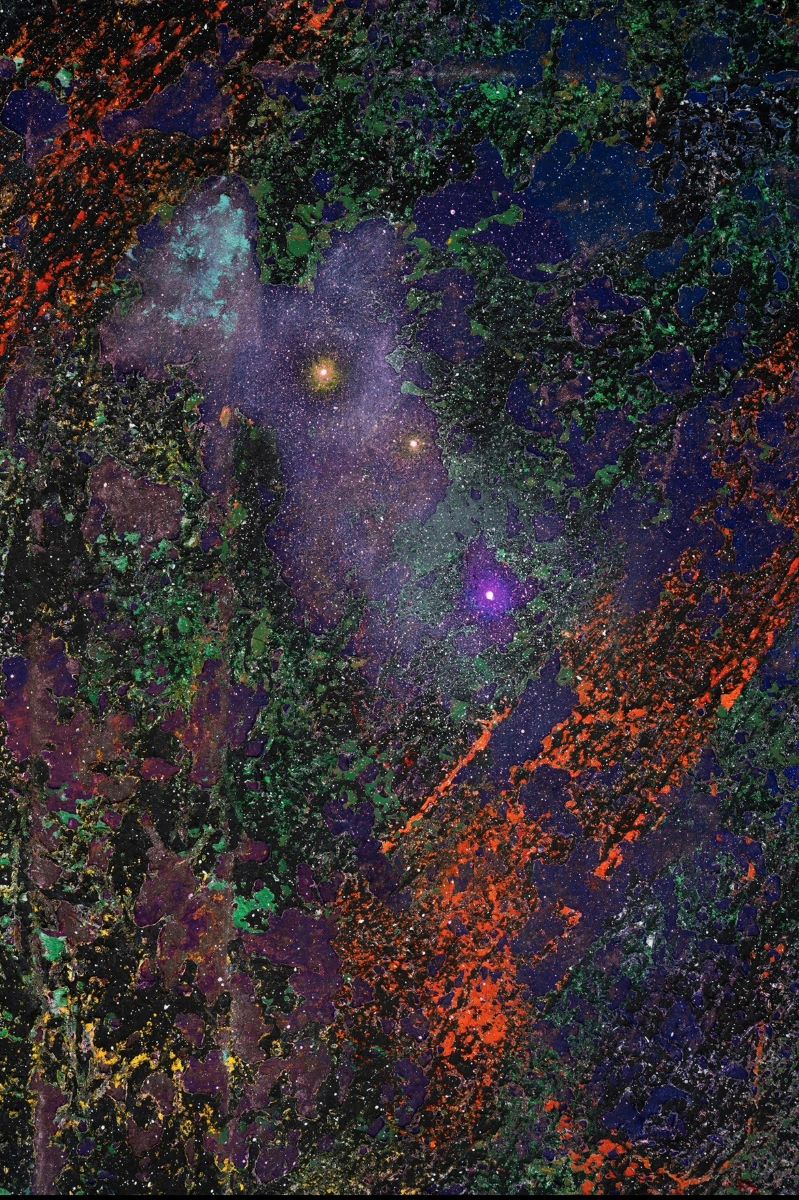

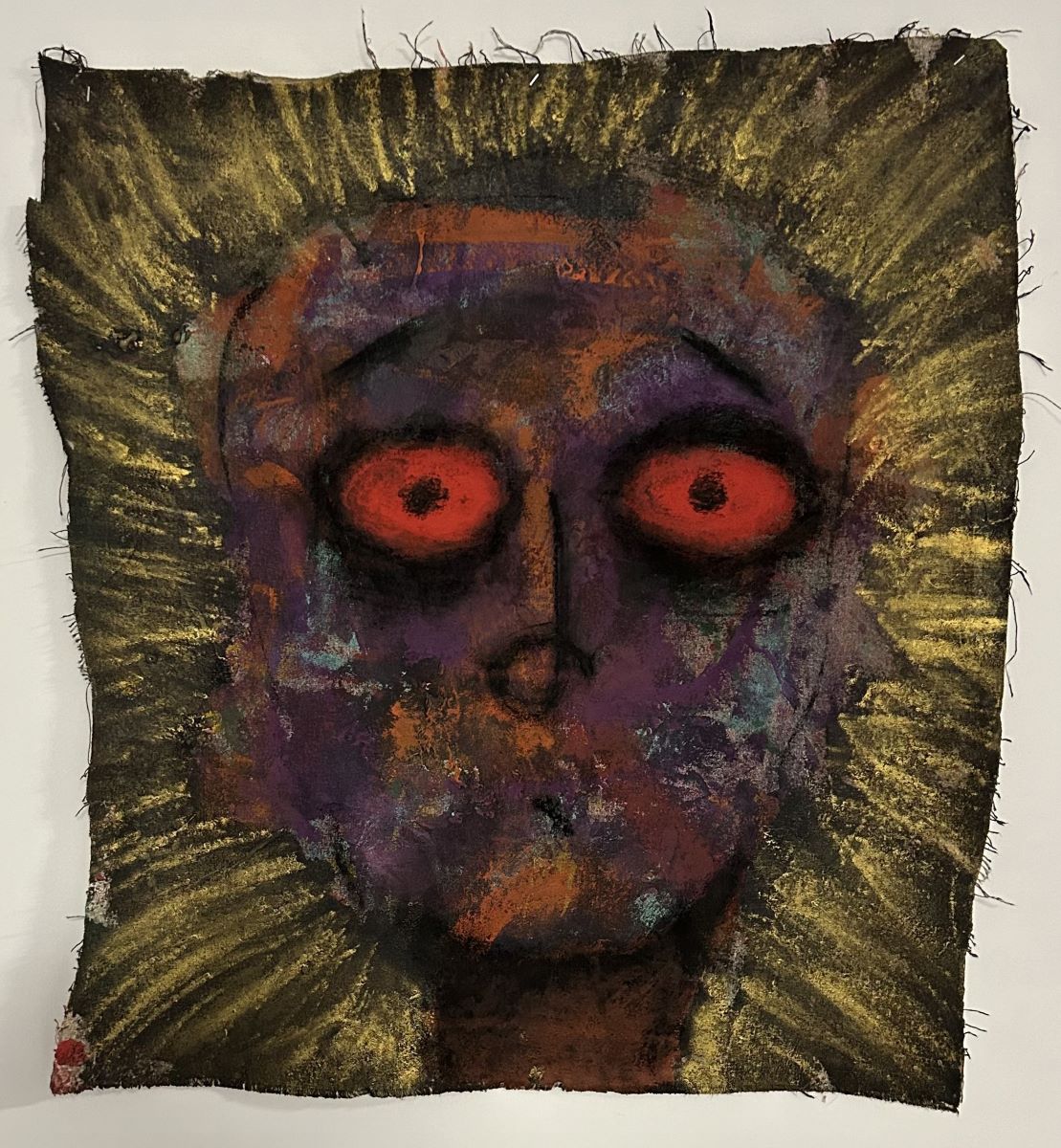

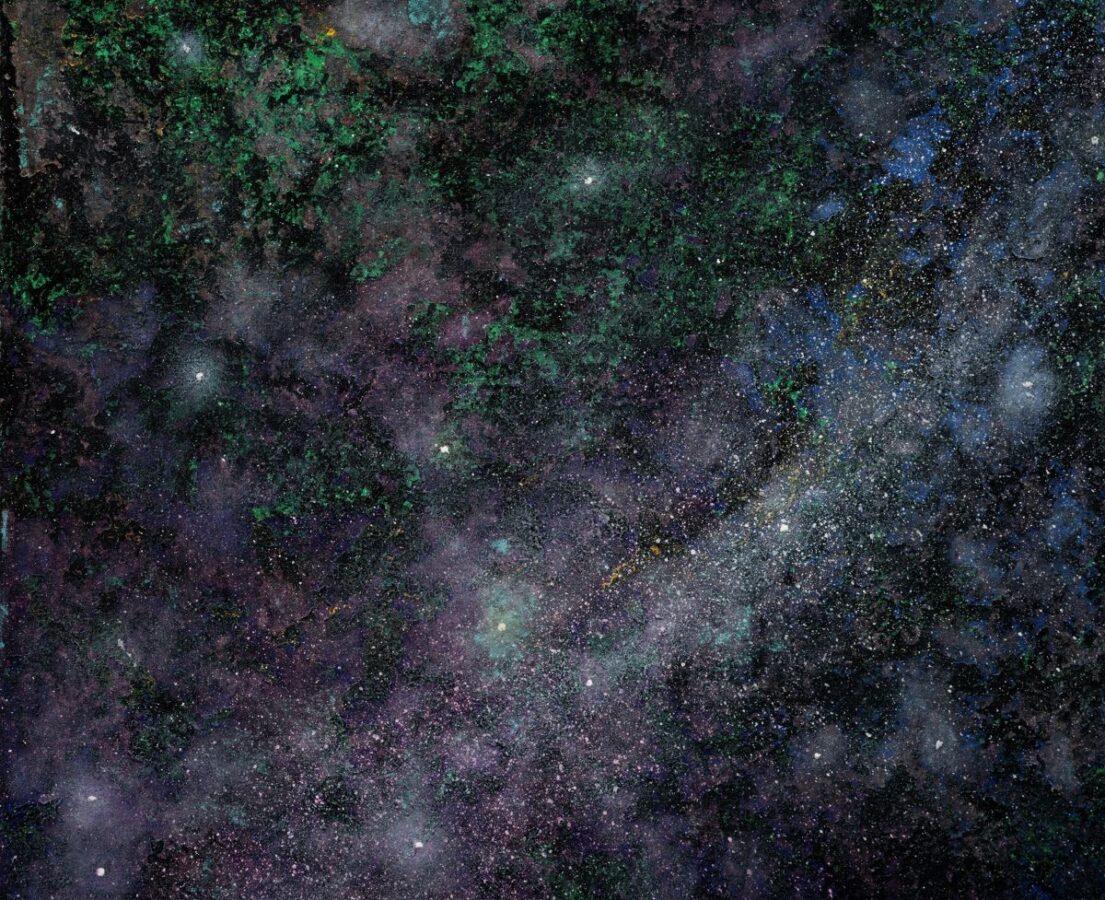

“What happens when you ignite gunpowder on canvas?” This was the question multimedia artist, Adewale Alli, asked himself after a particularly inspiring lecture in an art history class he was taking at the Community College of Baltimore. Alli, then in his early twenties, had recently moved to the United States from Nigeria. He was an economics major, pursuing a bachelor’s degree he’d begun in Africa but that he’d been forced to restart in the US. “I was required to take an art elective,” Alli reflects, “so I decided to take art history.” Although it was a general survey course, the class propelled Alli into the fine arts world, permanently altering the trajectory of his professional career and life.

Alli’s interest in art emerged during his childhood. Fascinated with drawing, he recalls teaching himself what he terms, “recognizable art.” To be “respected as an artist in Nigeria,” he explains, “you had to be able to make art that people recognize” —“realistic” drawings and paintings, in other words. Moving to the US as a young adult exposed Alli to a wider range of aesthetics and forms of creative expression. “I finally had access to more of what was going on,” he says, within, not only the art world, but also contemporary society broadly.

Alli was raised Christian. His mom is, and has always been, “guided by religion.” Consequently, throughout his youth, Alli found inspiration in Christianity. This relationship morphed when he entered adulthood: “I [began] to view religion as storytelling,” and “[also] realized I wanted to be able to identify with more [beyond] religion.”

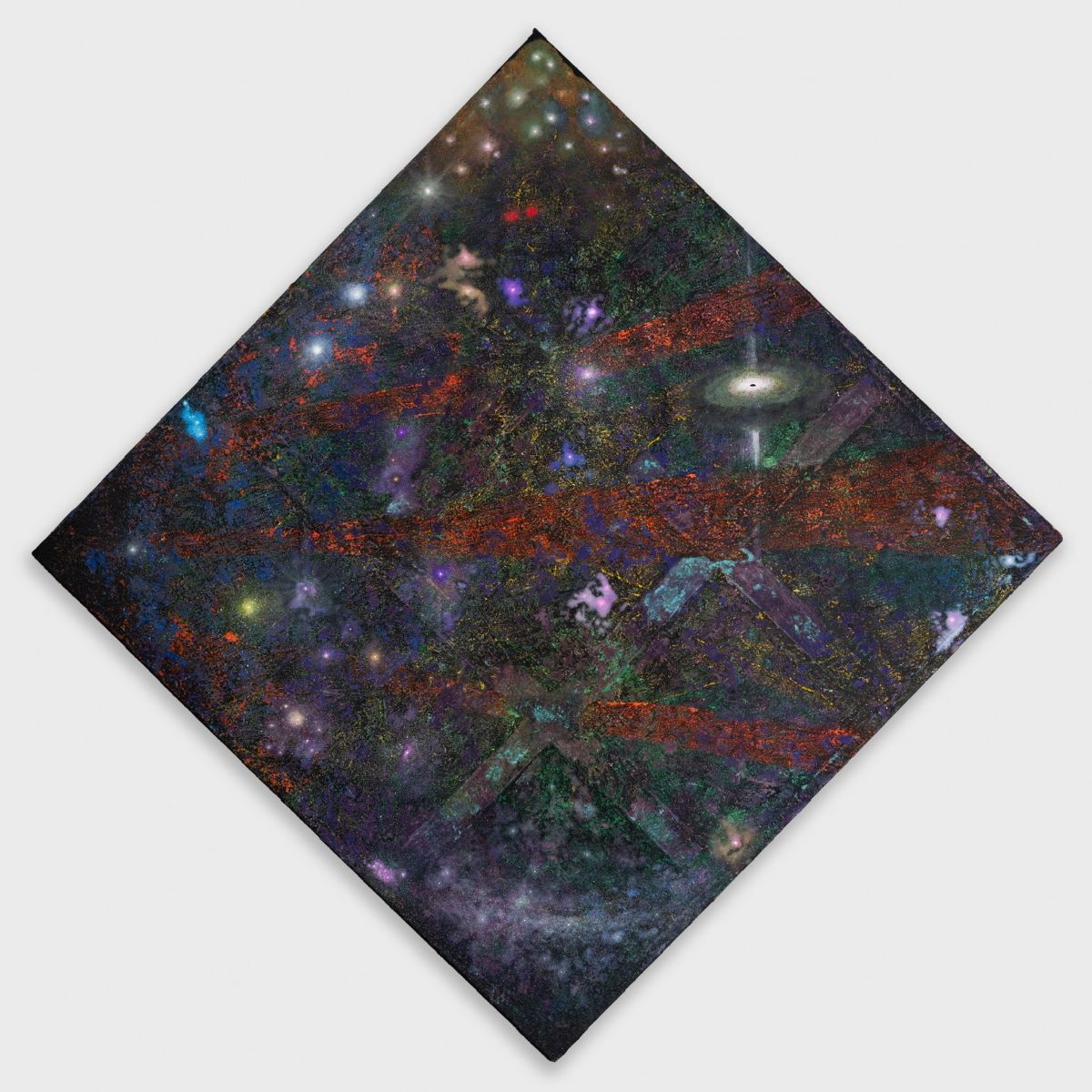

Treating ‘religion’ as a topic of interest rather than a way of life made space for the artist’s expanding curiosity in art. Alli considers his trial with gunpowder his first “leap into [the] fine art world,” but his explorations didn’t stop there. In fact, Alli’s practice continues to be defined by, and rooted in, innovation and invention.