It’s a strange experience to live, for the first time, in a place that’s central to the cultural movements and historical narratives that have shaped your tastes and interests. Especially when that place has changed as much over the last few decades as New York City. My assumptions about the city—largely based on the narrow (and romanticized) lens of American art history — are often wrong or out of date.

I’d always thought of the Chelsea Piers as a space of anarchic urban limbo, filled with illegal art installations and public sex. You can imagine my surprise when I learned that the Piers are now home to a massive sports complex, complete with a driving range, bowling alley, and ice skating rink. The Bowery has always brought to mind Martha Rosler’s The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, which juxtaposed images of empty bottles littering the streets with euphemisms for intoxication. Her representations were intentionally inadequate then; they’re now also outdated.

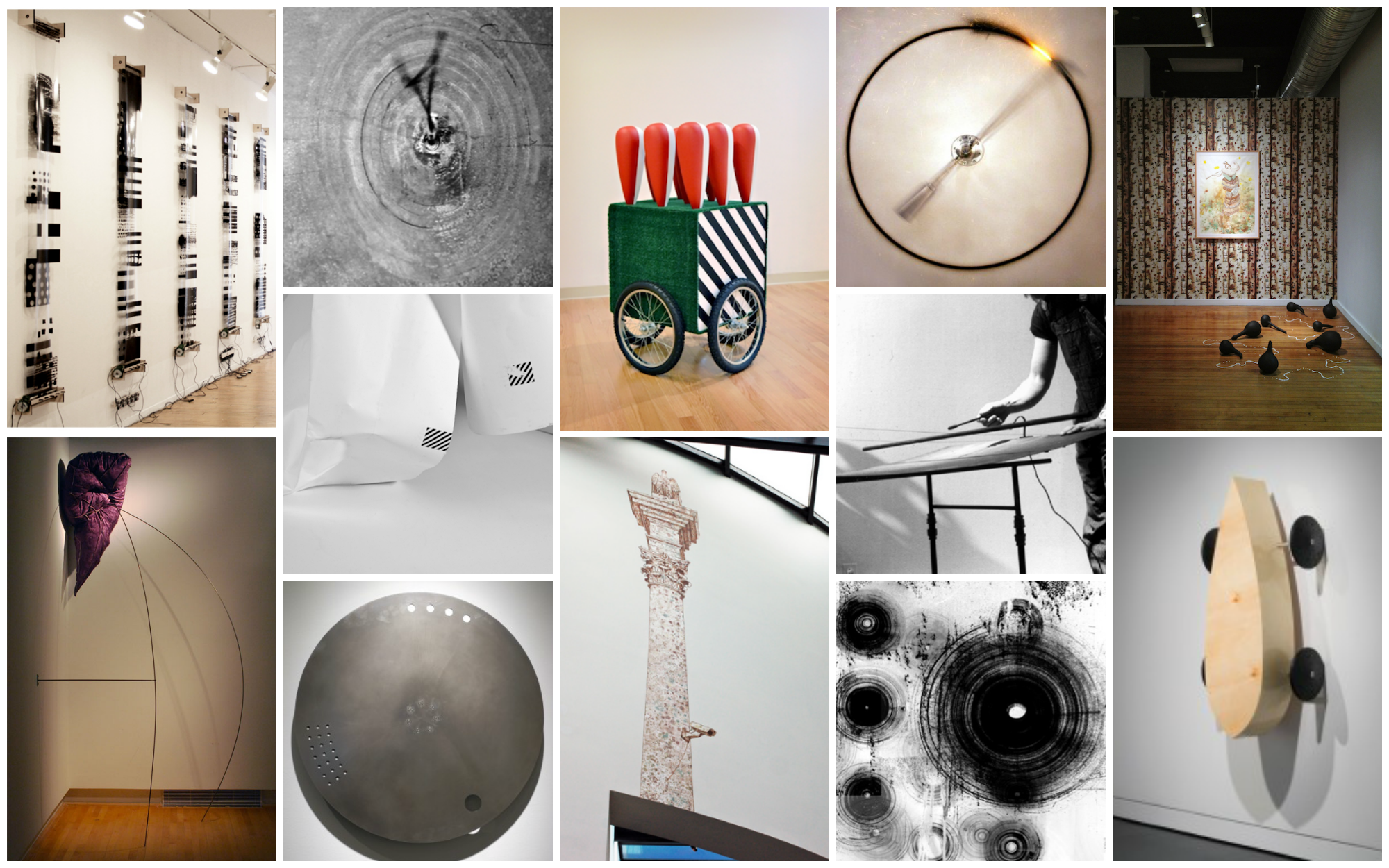

All of which makes it entirely appropriate that, on a recent trip to the Bowery, I encountered work exploring the distinction between reality and its representation, along with a show that gleefully explores the ways we appropriate and transform cultural symbols. If life in New York isn’t exactly what I expected, it’s not simply because my expectations were out of date; it’s also because cultural representations—works of art, books, movies, TV shows, music— can never represent a place with complete accuracy. The map is not the territory, after all. That skating rink at Chelsea Piers? It’s been there since 1969. I can’t blame all of my flawed expectations on changing times.

Unconditional Love, the third solo exhibition by British artist Matthew Stone at The Hole, features a series of works that combine painting with digital image-making to challenge the way we encounter both. To create the work, the artist paints expressive, thick strokes of paint onto glass. The surface is then scanned and the resulting digital images are edited to heighten their intensity. The results are printed onto a ground: panel, mirror or clear acrylic.

What this process-oriented explanation fails to capture is the physical presence of the works, the lushness and depth of the surfaces Stone creates. They’re visually alluring, combining a contained chaos drawn from abstract painting with the verdant colors and slick surfaces of advertising. Stone builds depth from layers of two-dimensional representation, creating visual complexity with the movement from painting to digital reproduction. But the sheer visual appeal of the works is twisted just so slightly by their unfamiliarity as objects. The viewer’s initial reception of the work is knocked off-kilter by the artist’s medium-based slight of hand. The result is a representational, uncanny valley, a subtle back and forth from ‘real’ to ‘representation’ that questions the definitions of both.

Stone’s craft and execution are critical to the success of the works in Unconditional Love. Sloppily produced, they could easily become an exercise in medium-specific naval gazing. Perhaps because it provides a sturdier ground, the works on board offer a visual depth missing from those on acrylic or mirrored surface. The board fixes the images into space, providing a flatness to support their appearance of depth. The works evoke both the fetishistic visuals of contemporary media and the celebrated brush strokes, drips, and pours of abstract expressionists. They reach out from the often inward-gazing practice of abstract painting, planting it firmly within the realm of contemporary visual culture.

As a nod to Stone’s multi-disciplinary practice, the exhibition also includes a three-channel video installation based on a performance that took place in the gallery space. The central video presents a staged dancer, dressed in black against a black background being filmed, at a close range, by a cameraman wearing a Steady-Cam and costumed in bright green. The interplay between these two figures holds the audience’s attention. The two other videos, projected on the left and right wall, seem to display the footage the cameraperson was shooting, featuring a single black-clad dancer in a black space. The work feels disconnected from the rest of the show, but also incomplete if considered in isolation. The two-dimensional works discussed above feel complete, fully formed and resolute, while the video installation seems unsure of its own intentions.

Photographer Laurie Simmons has long had a fascination with dolls. In her early work, she utilized dollhouses to construct elaborate tableaus. More recently, her series The Love Doll included images of life-size sex dolls, posed in mundane and everyday environments. She builds on this past work and digs deeper into doll-based subcultures in Kigurumi, Dollers, and How We See at Salon 94. Kigurumi is a sub-subculture, the most committed and perhaps confounding constellation in the anime and “cosplay” universe. Also referred to as “Dollers,” participants don elaborate doll masks and full body fabric or latex suits. The masks are cartoonishly oversized, complete with massive anime-style eyes, and attached wigs. The suits match the skin color of the masks and cover the wearer’s flesh with a flat, artificial surface.

Simmons’ photographs feature models dressed in full Doller gear. The prints highlight the imperfections, the moments when the materiality of the costume disrupts the fantasy. The eyes and lips on the mask appear hand drawn; the body suits bunch and wrinkle. These imperfections are evidence of human bodies beneath the costumes, proof that the images aren’t digital constructions or documentation of inanimate dolls.

There is something peculiarly contemporary about the Kigurumi subculture, with participants’ commitment to becoming a representation. Doller costumes are bulky and wearers have difficulty navigating physical space and interacting with other people. The point is to be seen, to be looked at, but not to act. By creating images of Dollers, Simmons’ is depicting people dressed as representations of the human form. Several of the images feature models whose arms reach out past the frame, as if taking selfies, a nod to the crucial role the Internet plays in Kigurumi culture. The Doller’s attempt to transform into a representation of a person, to flatten out reality, ultimately results in additional layers—layers of meaning, layers of fabric on flesh, representations of people costumed to mimic representations of people.

Pastiche Cicero, a solo exhibition by Timothy Hull at Fitzroy Gallery, displays the artist’s interest in the lives of cultural symbols, the ways they take on new meanings as they change hands and are passed down through history. The show is dominated by symbols and imagery that evokes the idea of Ancient Greece for contemporary audiences. From the sororities and fraternities that constitute ‘Greek’ life at America’s universities to academic conversations about the construction of sexuality, Ancient Greece holds symbolic charge through disparate areas of contemporary culture. The artist takes a clear pleasure in manipulating these meanings, both celebrating and gently mocking the strange lives of cultural symbols.

Stone is known for his incredibly detailed drawings executed with ballpoint or gel pen and there are several on display in the exhibition. “The oracle of Delphi One” and “The oracle of Delphi Two” depict the famous site in meticulously crafted blue ink, depicting a relic that has survived thousands of years with a throwaway invention birthed in modern times. While the pen on ink works are highly detailed, most of the show’s imagery is intentionally flat, depicting objects as silhouettes against a flat background. “Copy of a Copy of a Copy/blue” depicts the silhouette of a generic Greek vase.

“Reel Around the Fountain” acts as the show’s penultimate punch line. Tucked into a back closet, the installation features a small urinal and walls replete with Greek symbols and homoerotic imagery. The small space overflows with symbolism, celebrating the breaking of aesthetic, symbolic, and corporeal taboos. The norms so exuberantly discarded include conventions dictating the appropriate uses of objects and physical spaces; Duchamp’s defilement of high culture with mass produced goods comes to mind, as does the use of bathrooms as a site for sexual encounters. More subtly, but no less gleefully, “Reel Around the Fountain” also reminds us that the symbolic umbrella of ‘Ancient Greece’ has come to represent both the sacred invention of democracy and a predilection for a range of taboo sexual practices, including group sex and sex between men. Cultural symbols are charged indeed and always ripe for reinterpretation.

**************

Unconditional Love: Matthew Stone

March 6 – April 6, 2014

The Hole

312 Bowery New York, NY

Kigurumi, Dollers, and How We See: Laurie Simmons

March 7 – April 27, 2014

Salon94

243 Bowery New York, NY

Pastiche Cicero: Timothy Hull

March 5 – April 20, 2014

Fitzroy Gallery

195 Chrystie Street New York, NY

Additional galleries in the area:

Lehmann Maupin

201 Chrystie Street

Eleven Rivington

11 Rivington Street & 195 Chrystie Street

On Stellar Rays

1 Rivington Street

Mulherin & Pollard

187 Chrystie Street

P!

334 Broome Street

Canada

333 Broome Street

Whitebox

329 Broome Street

* Author Blair Murphy is a writer, curator, and arts administrator who recently relocated to New York City from Washington, DC. During 8 years in DC, she worked for a number of local arts organizations, including Washington Project for the Arts, DC Arts Center, and Provisions Library. Read more at blairhasablog.blairmurphy.com and follow her @blair_e_murphy.