Joyce J. Scott and Paul D. Miller (aka DJ Spooky) at Goya Contemporary reviewed by Susan Ren

Media and consumer culture shape society through perception, and artists are similarly susceptible in this cycle of culturally mediated change. On the surface, adjustments are made in an attempt to be up to date, but the ideas that lie within have seemingly remained the same. Issues such as government surveillance, racial and gender equality, and gun violence are commonly addressed in contemporary artwork in a multitude of ways. In the end, similar messages are received, but the delivery of that message takes a variety of forms, often depending on what media dictates to be in style.

Renowned artists Joyce J. Scott and Paul D. Miller (AKA DJ Spooky) have both managed to maintain the quality and relevance of their work, without the need to seem “current.” Both speak to issues in American culture by way of storytelling. Goya Contemporary presents an exhibition of Scott and Miller’s confrontational sculptures and images that get straight to the point.

In Can’t We All Just Get Along? Joyce J. Scott addresses the human condition in a state of manipulation – particularly, how gun laws have affected the culture. Her mixed media sculptures, a reaction to recent occurrences of gun violence in schools and communities, display figures of women and children constrained by weapons, as if an ominous force has decided their fate. Using intricate, delicate materials such as glass and beads, which commonly correlate with more feminine processes in arts and crafts, Scott maintains the innocence in her figures while also displaying the injustice in using violence as power.

Specifically in Scott’s piece Sex Traffic, a delicately beaded figure of a woman is bound, straddling an erect musket that stands upright, a formula used for traditional monuments celebrating male power. Compared to the musket, the woman is small and weak, overlooked and unwillingly controlled by it. The work addresses male dominance in gun culture, how violence can be used to overpower over or manipulate – in this case, Scott is specifically addressing the sex trade. This sculpture is simpler than the others in the exhibit, but also the most specific in meaning. Her work defiantly expresses that the freedom to own weapons diminishes the freedom of others who face violent control.

Even in her War Woman series, in which the women stand upright and unconstrained, they are surrounded and trapped by weapons – guns made of clear glass that resemble ice sculptures, which are delicate and appear to melt away. Depicting guns with a fragile nature implies the complexity and dysfunction involved in using violence to gain power. Similarly, in smaller pieces, she uses thread and beads to dismiss the masculinity associated with the figures. Scott’s crafting is intricate and decorative, and when juxtaposed with harsh content, her material choice becomes a significant part to understanding the story behind each of her sculptures.

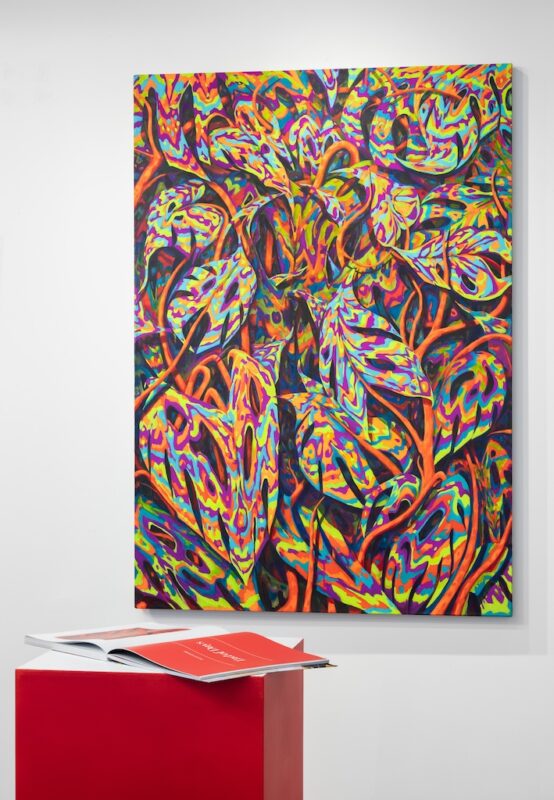

In contrast, Paul D. Miller’s Surveillance series displays digital prints of appropriated and collaged imagery. Though he does not specifically address fear itself, he communicates the feelings of “always being watched” in his work. His collages of camouflage designs and fragments of the American flag, intertwined with black and white barcodes and other codes and symbols, indicate government encryption and suggest their wide ability to watch over citizens.

Anyone can use a smartphone to scan a square, black and white QR code and be presented with all manner of information, as appropriated by the artist in this exhibit. However, what is more interesting than the abundance of these barcodes, is the assumption that everyone has a smartphone to scan it with. Miller’s work notes this growing use of technology, and takes it further to suggest the government is using this widespread access to technology to track individuals and their activities A general paranoia involving surveillance already exists, and Miller has created a collection of visual representations for these suspicions.

Unlike the rest of the show, his two monochromatic black and white prints appropriate characters from Alice In Wonderland. Compositionally and conceptually, these prints do not have the same feel of his other, more graphic works. Here the characters appear “imprisoned” and controlled by consumer culture—with no overt relationship to surveillance. This subtlety makes them stand out as Miller’s most visually appealing works.

Joyce J. Scott and Paul D. Miller address how different levels of power affect people, using distinct and detailed techniques without abstracting their ideas. In their work they recognize the ubiquitous influence of the media, and they further question how societal behavior has changed as a result. By retaining a broad but direct focus, their work’s inherent messages can be widely consumed and discussed, creating a contradictory narrative against the mainstream media.

Author Susan Ren grew up in Columbia, MD (where she often felt misplaced) and graduated from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (where she felt only a little less misplaced). She is now a Baltimore-based visual artist, photographer, writer, cat lover, and DIY-enthusiast in a city that feels right.

* Photos by Susan Ren and Joe Hyde for Goya Contemporary.

Joyce J Scott: Can’t We All Just Get Along? and Paul D. Miller: Surveillance at Goya Contemporary through November 7, 2014

Mill Center, Studio 214 / 3000 Chestnut Avenue / Baltimore, Maryland 21211