Read the Recap, Skip the Show at Guest Spot reviewed by Ryan Syrell

Read the Recap, Skip the Show at Guest Spot grapples with the superabundance of online art documentation, and its expedited, high-volume digestion by a globalized audience. Every exhibited art object begets innumerable online doppelgangers, resulting in a nearly innavigable glut of imagery and analysis. Read the Recap makes a powerful case on behalf of the untranslatable experience of having actually shared space, and spent time, with art. There are particulars which make every encounter with art essentially site-specific, and the expansive contextless nature of the internet tends to wipe clean most of this information.

That being said, beyond this curatorial focus, each of these six artists create work concerned with process, reference, and materiality. Part of what makes this show work so well is the easy give and take between the individual concerns of the artists and the framing narrative of the curation. Most of the work is strong enough to enter into the show’s dialogue while maintaining it’s own conceptual integrity.

Paul Gagner’s Under Consideration sets the tone for the show; it’s the first object encountered in the space, and it addresses a number of the show’s themes. In these oil paintings, surface is of central importance. Surface is ever-present when discussing painting, and just because a painting has a surface doesn’t mean that it’s doing anything, but in this case it really is the crux of the physical and conceptual goings on.

Each canvas is initially executed as an all-over abstraction; a heavily worked field, plowed through with a painting knife, producing a series of ridges and troughs. These nebulous grids form the ground for a second round of painting; studio scenes, in which Gagner’s initial abstract image figures prominently as a parenthetical painting-within-a-painting. This is a tried and true device, but with Gagner’s residual palimpsest operating as an incessant reminder of the duality of the painted surface, the painting never resolves completely into a simple picture-in-picture. We are aware of a presence that we can only see in part, calling to mind earlier notions that abstract painting was capable of presenting the intangible and inexpressible world that exists beyond the visible.

Jeremey August Haik’s photos are immediately attractive, but are not major players in the dialogue of the show. As collage-based photographic works, they operate well within the referential structure necessitated by the curation, but their slickness of execution and their primacy of imagery over objecthood simply leaves them with less to contribute. Of all the works in the show, they would appear to lose the least in translation between object in situ and image on screen.

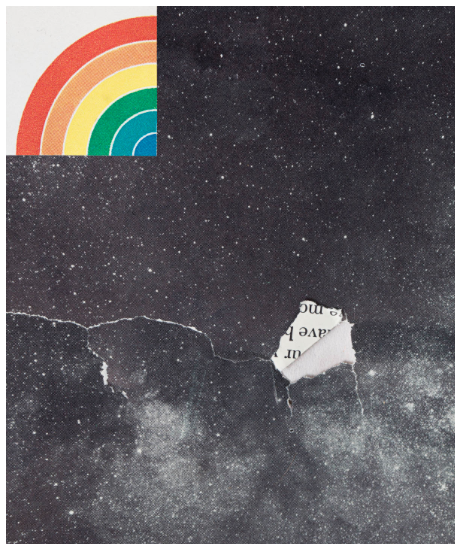

2-up with Spectrum is a bold but cryptic image, in part due to it’s abandonment of classical figurative reference found in Haik’s other works. A triad of elements ( a punctured image of deep space, an exposed fragment of text, and a graphic rainbow) elegantly jostle one another formally and conceptually; with the rainbow as electromagnetic spectrum, text becomes analogous to radio communication across the void, or, text as the word of god, emanating from the cosmos, with rainbow as notation of the covenant.

Not What It Is But How It Is, by Heather McKenna (pictured at top in frames) exists as a second-degree object. McKenna created the sculptures pictured in her photographs, which are also exhibited, although not in conjunction with one another. This practice typifies the complex relationship formed when one artwork spawns a closely related “other.” Bruce Nauman stated his tendency to “re-make it and re-make it and re-make it and to try every possible way of re-making it,” in doing so the similarities and echoes are obvious enough, but zeroing in on the differences is an important exercise in seeing and mindfulness.

Perhaps it’s the presence of Haik’s classical references, but McKenna’s arcs, points and angles seem to operate as Euclidean concepts made physically manifest, then pushed back toward the ethereal by virtue of their reinvisioning as formal photographic elements. Painted frames and triptych hanging keep the whole a suitably ambiguous blend of object and photograph.

Björn Meyer-Ebrecht’s free-standing wood and book sculptures establish a balance between the refined formal qualities demanded by modernist doctrine, and the look of prototypes or working models. Where one would assume to find a pristine, machine finish, there are instead irregular seams, knot holes, visible kerf-marks, all enclosed in a skin-like, hand-painted surface; a commentary on the disparity between the idealism of theory and the actuality of practice? Regardless of whether or not that’s the case, the objects work stunningly.

The particular vocabulary of modernist forms used here are customarily monumental in scale and industrial in material. In Meyer-Ebrecht’s variants, they embody a human scale, and are fabricated with an unmistakably human touch. The dimensions of each sculpture’s wooden elements appear to be derived directly from the dimensions of their corresponding book component. The conjoining of theory (e.g. Art and Society: Essays in Marxist Aesthetics) and form at this size serves to populate the gallery with strikingly uncanny modernist totems.

Margo Benson Malter’s fabric works are exciting and delightfully baffling objects: two wall mounted quilts and one free-standing textile-shrouded structure. Malter quilts with cotton and tyvek, using digital and hand printing; her digitally printed fabrics are adorned with hands, abstract patterns, and internet pop-up ads. This presence of ads echoes earlier quilters’ habit of recycling patterned feedsack bags, designed by competing companies aware of the reuse of their textiles; advertising recycled into formal components.

After Judd II implies an additional reading: sewn fabric as repetitive, geometric, manual labor. It calls to mind associations between the uncredited fabricators of minimalist sculpture and the unattributable quilts of the 18th century (which prefigured the squares, rectangles, and patterns with limitless variations so prevalent in the work of Judd, LeWitt, et al).

Situated in Guest Spot’s rear gallery, Joe Nanashe’s 3xladyx3 is both ludicrous and insightful. It’s a straightforward idea: three live video recordings of Lionel Richie performing Three Times a Lady, projected on a wall simultaneously. That much, at least, is easy to describe; but trying to process the interaction between the layers upon layers of schlocky faux-sincerity is something that really requires direct observation. Beyond the jokiness of it, it’s a concise document of what happens to a performance over time.

Nanashe’s other video work, 1kHz Test Tone and Color Bars, is a little less funny, but maybe more absurd. In it, the artist (on one monitor) does his best to match pitch, by whistling, with the relentless whine of a TV test signal (on another monitor). The inaccuracy of Nanashe’s pitch results in an cacophony of difference tones, while his determination never seems to let up. It’s reminiscent of Mitch Hedberg’s line, “the depressing thing about tennis is that no matter how good I get, I’ll never be as good as a wall.”

Author Ryan Syrell is a Baltimore based artist.