Michael Farley on Prospect New Orleans 3 – Part One in a Series

I’m in New Orleans for the third installment of the Prospect Biennial (P.3), but I’m having a hard time believing it. Beyond the fact that New Orleans itself (in all its familiar exoticism and permanent state of transience) feels like a delightfully illogical dream, it seems like there isn’t a major international art event happening here.

There’s a lot of promotional hype surrounding the biennial, but surprisingly little content considering the amount of work visitors have to do to find the venues. Mostly, however, it seems like the entire city of New Orleans is either unaware of (or totally indifferent to) P.3’s existence. When I meet new people, they’re genuinely surprised to hear that I’m just visiting and haven’t just moved here. When I tell them I’m in town for Prospect, the usual reaction is “What’s that?” followed by “oh, you should’ve come next week! Dia de los Muertos will be much better!” Most surprisingly, I even find myself having this conversation with the majority of the many MICA alumni and dropouts who left Baltimore in search of even cheaper rent and even weirder culture than we pride ourselves on back home.

Some of this indifference may be wounded pride or distrust of the biennial’s somewhat charitable mission statement. Prospect began with the intent to factor “cultural capital” into the post-Katrina rebuilding (and re-branding) of the devastated city. But New Orleans isn’t lacking in culture— it just happens to have a radically, wonderfully idiosyncratic culture that doesn’t necessarily use (or have any interest in) the type of cultural currency that New York, Venice, Cologne, or Berlin have and cities like Miami and the “emerging” art centers of the global south desperately want.

And New Orleans certainly doesn’t need boosterism. I haven’t met a single person who has visited this city and not fallen in love with it. Even I (dedicated lifelong-Baltimorean who has scoffed at the very idea of moving to Oakland, Bushwick, Berlin, or Portland) find myself fantasizing with other visiting artists about finding a cheap, lopsided little apartment off St Claude and taking a part time service industry job in the French Quarter. One thing we don’t often talk about is the art.

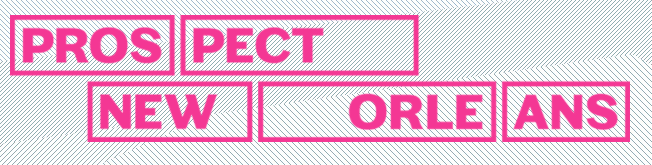

Most of the P.3 promotional materials indicate scattered sites across an impossible-to-read map with no addresses or public transportation information. Apparently there is a “guided tour” on bikes for $80—laughably out-of-budget for most city residents and visiting artists and writers. I’ve heard that sometimes there are shuttle busses but these have turned away artists showing in the biennial for some reason. The “planning your visit” tab of the website is a maddeningly complicated string of event closures and clauses like “Prospect is FREE* (note: certain venues charge admission).” The website DOES offer a one-time code for a $20 Uber credit, but Uber doesn’t seem to work here yet? Most perplexing, many sites decide to close at 4pm in a city that unabashedly sleeps-in well into the afternoon. Most events are over before most people realize they are happening.

When friends and I took a cab to the out-of-the-way May Gallery to see Tameka Norris’s show, even our driver (a neighborhood native) got lost. The work itself seemed just as directionless. The gallery had no printed information about the artist or her work (which isn’t necessarily a bad thing) but here it was problematic. In a dark room, we (and the small handful of other attendees) encountered several videos (some loops and one that was a longer “narrative” that most people couldn’t sit through) and some mixed-media collages. The collages are sweet and painterly— incorporating things like scraps of fabric and nice surprises like bits of string with the needle still dangling— implying a paused, uncertain process rather than a completed art object.

I first assumed that the videos were an unsuccessful attempt to translate the successful qualities of the collages (personal v.s. found, hard v.s. soft, etc…) into a new (presumably unfamiliar) medium. The “narrative” piece is a disjointed collection of scenes that read like an indulgent reality tv show: the artist cries. The artist looks bored while a cab driver talks to her. The artist cries more. The artist sings karaoke at an art opening. It’s an awkward mash-up of clips that look like documentary shots and painfully staged dialogue. The whole time I watched it, I found myself gazing at the New Orleans streets where the majority of the video was shot and wishing I was back in them. It’s a recurring issue I encountered with a lot of the work at P.3—work created for or about the context of New Orleans can’t hope to be as impossibly interesting as the city itself is.

Later, I read the project description on the Prospect website. It’s supposedly about a fictional alter ego maturing as an artist while the city grows with her. There are lots of buzzwords like “identity” and “gentrification” that make the artwork itself seem like a homework assignment to produce something “relevant.” I felt cheated by my interest in the collages (which make a cameo in the video). Are these the work of the fictional artist? Mere props in a film? A deception? Or is this what Tameka Norris actually put her heart and soul into producing? Does the constructed narrative serve as an attempt to “justify” a studio practice as something that’s “engaged”?

I wanted to know the person who made these objects, with all their funny vulnerability and peculiarities. The tone of Prospect, however, seems to imply that artwork isn’t enough. There’s a slightly off-putting tendency at P.3 to highlight the “otherness” of the artists or remind the viewer that contexts they exhibit in are politically-charged. It’s strange because it doesn’t always seem like these gestures are telling us anything new or doing so in a way that feels productive.

A less direct attempt at site-specificity is often more successful. At Uno St. Claude Gallery, the Propeller Group takes an unusual and utterly compelling approach to engaging with the local culture. Their epic, visually lush video “The Living Need Light, And The Dead Need Music” follows a funeral procession in Vietnam through narrow streets and theatrically lit dark spaces. It’s a seductive feast for the eyes—elaborate costumes, musicians, fire eaters, professional mourners, and a gender-ambiguous hostess of sorts move through a dream-like sequence of actions and tableaus. There’s an obvious correlation to the local funerary rites of New Orleans. On opposite sides of the globe, two former French colonies spin brass instruments, hybridized Catholic symbology, fluid gender roles and an almost celebratory attitude around the universal constant of death. The video is contextualized in the gallery with real instruments and photos of New Orleans marching bands.

These photos seem unnecessary and don’t add much to the work. I’d rather be allowed to make the connection between the two cities than have it spoon-fed to me. Indeed, I’m finding it strange how often representations of New Orleans seem redundant— it’s a locale that’s been so thoroughly documented in films, television shows, literature, pop culture, and news reels that I haven’t been tempted to take a single photo as a tourist here. It’s a little like entering a postcard. In fact, part of what I like about the sleekness of “The Living Need Light, And The Dead Need Music” is its visual correlation to American music videos, in which New Orleans is a frequent backdrop.

That said, this piece makes a better case for resisting the homogenization of New Orleans than more direct attempts at activism-art; here we see two cities that share distinct but interrelated identities as the bastard-children of globalization, defiantly unique and worth preserving.

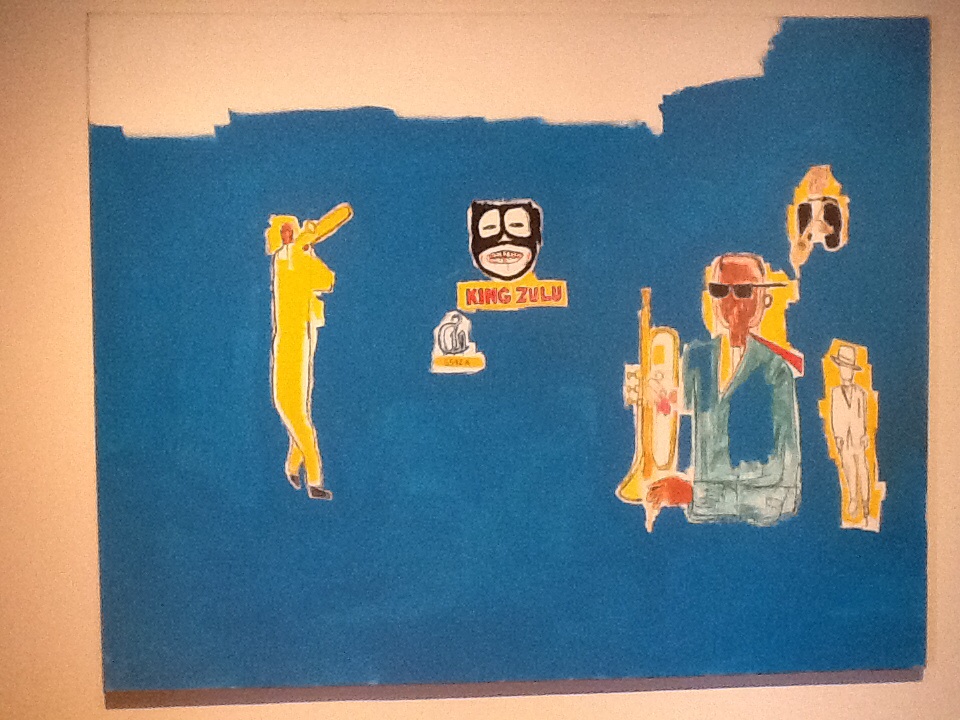

One of the P.3 programs I was most excited about seeing was “Basquiat on the Bayou” at Ogden museum of Southern Art. The exhibition is a collection of works that address how The South (namely it’s prominence in the American saga of the African Diaspora) informed Basquiat’s practice. It’s an interesting premise. Most of the work was produced several years before Basquiat’s first and only visit to New Orleans a few months before his death, meaning that his work was informed by “The South” as an abstraction, a near-mythological place that exists in the American psyche as much as on a map.

Overall, the show is a disappointment. There are only nine pieces on display, tucked away in a dark chamber on the top floor of the museum. Visitors must pass through a gauntlet of security, a $10 admission fee, and more wall space devoted to pedagogical text and timelines than actual artwork. There are a few highlights, but it’s mostly a room of Basquiat “B-sides.” The casual “southern-ness” of Basquiat’s work—informal mark making on found materials, borrowed vernacular, improvisational energy— are totally negated by an exhibition designed to instill a sense of preciousness to the pieces we all already know are worth millions of dollars. In addition to the dark, reliquary-like lighting, there’s a three-foot perimeter chained off around each piece that makes getting a closer look or observing detail impossible. Coupled with the forced procession through wall text and scarcity of works on display, it feels exactly like picking up a museum brochure and looking at thumbnail images designed to illustrate a catalog excerpt by a curator.

I’m a huge Basquiat fan, so the let-down might be partly my own overly-high expectations. I was first exposed to Basquiat’s paintings at the IVAM in Valencia, Spain as a teenager. I credit that exhibition with inspiring my love of art—the bright, cheery Spanish museum seemed to celebrate a feeling of liberation in the expressive canvass.

Here, perhaps appropriately, the work coneys a somber reflection on bondage. “Back of the Neck” and “Untitled: Cadmium” both exemplify Basquiat’s interest in anatomical illustrations gone awry. Here, however, the disembodied torsos and grotesque contortions are inescapably tied to violence against a de-personified body. Black figures juxtaposed with corporate logos in paintings like “Zydeco” suggest the flesh made commodity. I couldn’t stop recalling the unwatchable scenes from last year’s American Horror Story, in which Kathy Bates played a sadistic slave owner who tortured her victims in an antebellum New Orleans mansion.

Even the contemporary South can be seen in this small collection of decades-old works by a man from Park Slope. “Procession” and “Embittered,” two mixed-media pieces on distressed wood from 1984, are strangely visually analogous to the post-Katrina streetscapes of the majority black neighborhoods that are still pockmarked by dilapidated white structures—chipped paint and cryptic graffiti (or condemnation symbols) and all.

And then there is the Ogden itself, a museum of Southern and “outsider” art that’s full of pieces one could seamlessly insert into the Basquiat exhibition without raising suspicions. I almost wish the curators had foregone labels and jumbled the galleries, leaving us to guess what’s homegrown and what’s imported.

That night, I stumbled across a pink P.3+ sign (implying a Prospect satellite program) on the hood of a car parked in the middle of an informal party in front of an autobody shop. I asked the bartender if this was someone’s installation. She shrugged, “it’s my buddy’s project… But it’s also the project of anyone who’s dancing.”

No one seemed to really know who had organized the pop-up party. I was finally directed to a man who identified himself only as “The Reader.” He seemed confused as to why I wanted to photograph his installation. I asked him about the P.3+ sign and he laughed “oh! I don’t know who put that there. But yeah, I guess this is art.”

Another guest offered: “Here’s the thing. No one here really gives a shit about the art world. Everyone here just does our own thing and don’t really care about getting famous as long as no one bothers you. We’re not even too concerned about gentrification. How can that last?” As I danced to someone’s iPod coming through a car stereo and enjoyed the novelty of being served alcohol on a sidewalk, I hoped he was right. Is there a candle someone can light to keep New Orleans like this forever?

P.3 is a huge event and I’ve just seen the tip of the iceberg, so I don’t want to pass judgement on the whole biennial yet, but it’s so far been much less interesting than its host city. It seems like the curators want to balance the global with the local, and strive to present the biennial as a political statement. But, in a sense, they’ve missed the most compelling aspects of the city: it’s simultaneously porous and mysterious, approachable but unknowable, loud but un-opinionated. The culture of display here isn’t about wall text, it’s about a chaotically improvised street theater. New Orleans is an accessible city in every sense— affordable, easy to wander, and friendly. There’s a generosity of spirit in terms of gifting an unexpected experience to strangers. So far P.3 has been the opposite— it’s logistically inaccessible and tells viewers exactly what to think.

There I go again with my Northern cynicism. I am going to try this non-judgemental New Orleans thing. It’s the least I can do, as I don’t eat seafood. Maybe in the next few days I’ll fall as much in love with Prospect as I have with everything else.