Elena Volkova reviews Khalik Allah: 125th and Lex presented by Randall Scott Projects and displayed at Area 405

Work displayed on a gallery wall, or on any wall, is typically assumed to be art. We can discuss content, intentionality, and skill; but, in the Post-Duchampian era the questions of whether something is or is not art are rare. Khalik Allah’s recent exhibition of photographs titled 125th and Lex conforms to this standard, but the ethics behind his work seriously question it.

During the early days of photojournalism, professional practitioners refused to be called artists. Photojournalism is a truly selfless field, with no place for ego; quite the opposite from the art world. In the past decades, we see an increasing number of photojournalist works showcased and sold in commercial galleries, which raises questions about photography as a medium, as an art form, and as a tool for communication and self-expression.

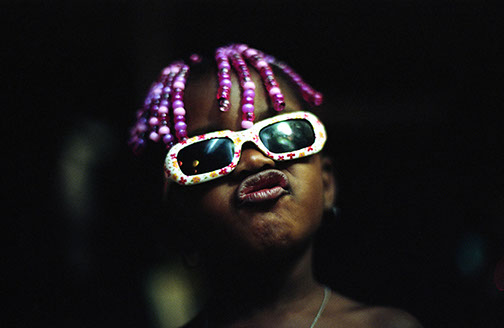

At first glance, I rushed to brush off Khalik Allah’s work as one of those photography shows that aestheticizes poverty and addiction. Shocking content, beautiful underexposures, rich colors, effortless compositions, expensive frames, and a predictable price tag… Highly educated audience, collectors, students, other artists… We are all touched by this work visually, and are critical of it when it comes to viewing it as a commodity. However, the question of whether photojournalistm has a place on a gallery wall keeps the boundaries of photography fresh and interesting. Allah’s work may equally be dismissed and celebrated as photojournalism, as well as equally dismissed and celebrated as fine art.

Listening to the artist talk about his work in videos and looking at the images carefully, while trying to let go of my assumptions, I couldn’t help but think that there is something poignant and honest that lies beyond my initial response. Allah possesses the unbiased eye of Jacob Riis, shock value of Boris Mikhailov, and the honesty of Shelby Lee Adams. The exhibition 125th and Lex may be about race, class, and the human condition, but most compelling is the story behind these images.

“Everything about me is of God. These are offerings of healing to the mind in the world of time,” Allah declares in a documentary video on the homepage of his website. He also affirms that he is not a fine artist, and that his appearance in art world is incidental and not deliberate. His honesty and selflessness truly caught my attention.

Raised on Long Island, Allah discovered Harlem during his tender teenage years when he was searching for spirituality and a new direction in his dismantled life. After over a decade of spiritual practice, he explained that his life experiences and attitudes are no longer informed by religion. Allah is a self-taught photographer and filmmaker, and he is cautious observing his work gain momentum in the art world.

The art in Allah’s work is not in the taking of the photo. It is not in editing, printing, framing, or exhibiting. It’s not even in the mental or artistic process. For Allah, the most compelling aspect of his practice is the connection he forms with the people whose lives he records; it’s the relationship and the level of trust that he builds with his subjects. It is the fact that everything about the people he photographs is “of God.”

What we, the viewers, experience in Khalik’s work is a visual record of that sublime connection.

Author Elena Volkova is a Baltimore-based photographer and a professor at Stevenson University.