First, a little historical background on Baltimore’s Percent for Art program: Originally passed in 1964, the program now “requires that at least 1% of all eligible funds for a [Baltimore City] construction project shall be allocated for artwork for that specific project or another public art use as determined by the Public Art Ordinance.” Only the second such initiative in the country (Philadelphia launched the first), it intersected historically with a surge in the need for new schools in Baltimore in the 1960s and 1970s.

Without the persistence of an advocacy committee, however, headed by artist and educator Joan Cohen, the Percent for Art program might not have been as robust at school sites as it turned out to be. The surge for new schools tapered off by the late 1970s as residents left the City, the overall population dropping by almost 120,000 in that decade, including a decline of some 27,000 students between 1972 and 1976, according to an article by Eli Pousson, with contributions from Ryan Patterson, both public art administrators/ scholars. Even with this falloff and the accompanying falloff of public artworks, the number of the latter sited in schools is well over 120. But today, exactly 60 years after the Percent for Art program was launched, many of these works are in dire need of repair. Thankfully, funding from programs like Maryland State Arts Council’s (MSAC’s) Public Art Across Maryland (PAAM) Conservation Grants, which started in 2021, is available to help address this need.

And thankfully, Carlberg’s “Caterpillar” is the recent recipient of one of these grants. Written by Cindy Kelly and local artists Linda DePalma and Mary Ann Mears, together known as Friends of Public Art, or FOPA, with Jubilee Baltimore serving as lead applicant (Jubilee is a non-profit, and FOPA is not), the grant provides $30,000 toward conservation. Other funding sources have provided $14,000 to complete the extensive conservation, which includes welding of corroded closures between units, installing flashing for water falloff, adding protective coating, etc. And here’s good news relevant to this column: The MSAC grant will also cover signage! Carlberg’s name, title of the work, and date will appear on a plaque outside the building, an educational panel will be installed in the school lobby, and a video about Carlberg will be posted on the school’s website and linked via QR code to the educational panel. FOPA’s been busy with other similar projects at city schools (stay tuned for future columns about those).

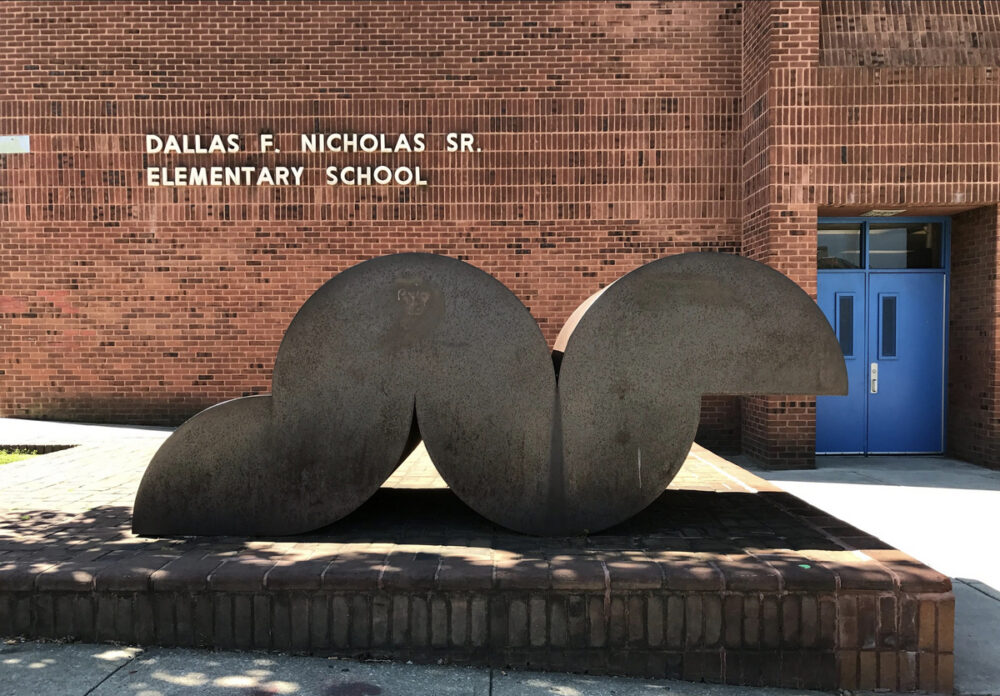

At last, information about this marvelous looking, gritty feeling, currently anonymous piece in front of Dallas F. Nicholas Sr. Elementary School will be available within the coming year to faculty, staff, students, families, and neighbors, to say nothing of visitors and tourists. The multitude of data points will no doubt get worked into curriculum, where they can only enhance and be enhanced by whatever story-finding and story-telling the students produce on their own. We adults will learn a great deal from the students as they unleash their much-more-story-imbued imaginations. As an art history teacher, I’ve always noticed how kids “get” abstraction much more readily than we grownups.

A scary example of adult resistance to abstraction comes from an anonymous anecdote passed along to me as I conducted research for this column: A former administrator at Dallas F. Nicholas Sr. Elementary School, who wasn’t a fan of the piece, was overheard saying they wanted to get rid of the work. The person overhearing the comment was a college art student intern, who remarked to the administrator that she was pretty sure the work was a bona fide fine art piece and, as such, should be preserved.

The administrator asked her to gather details, and she came back with the artist’s name, artwork’s title, date, and more. The administrator’s response: “Oh, they’re caterpillars! So, as part of your internship, can you paint them to look like caterpillars?” Thankfully, she declined. And now signage is on its way to avert such near misses in the future.