A Conversation with Bonnie Jones by Kimi Hanauer

Bonnie Jones is a Korean-American writer, improvising musician, and performer working primarily with electronic music and text. Born in 1977 in South Korea she was raised on a dairy farm in New Jersey and currently resides in Baltimore, Maryland. Bonnie creates improvised and composed text-sound performances that explore the fluidity and function of electronic noise (field recordings, circuit bending) and text (poetry, found, spoken, visual). Bonnie has received commissions from the London ICA and has presented her work in the US, Europe and Asia and collaborates frequently with writers and musicians. She received her MFA at the Milton Avery School of the Arts at Bard College.

Go to www.ifiruledtheworld.info

Kimi Hanauer: What is your radical improvisational approach to music and sound and all about?

Bonnie Jones: I think this is a discussion that most people are still having, what does it mean to make political music, or have radical action inside of music?

My approach to improvisation didn’t come from being a jazz or electronic music scholar, or even a trained musician. I came to this music through the people who were playing improvised music in Baltimore in the late 90’s and early 2000’s. People like Dan Breen, Catherine Pancake, Andy Hayleck and many others involved in the Red Room and High Zero Festival community.

When I started improvising more heavily, what was immediately special about the music was that there was almost no barrier to entry, no requirement to be “virtuosic” on your instrument and very little hierarchical structures. Also the music was largely focused on collaboration. It’s one thing to have an improvisatory practice on your own, but shifting that into a context with other musicians and live audiences felt like a really radical way of producing music. I can’t think of many forms of contemporary art-making that have deeply established and active communities with these particular characteristics.

What was immediately special about the music was that there was almost no barrier to entry, no requirement to be “virtuosic” on your instrument and very little hierarchical structures.

KH: What is the relationship between the inherent qualities of improvising and the capitalist system we live in?

BJ: What drew me to improvised music initially was how disruptive the practice was to the process of establishing value, determining criteria and creating cult of personality; all things that work to create reproducible and valuable products. Also, because I was always improvising with other people, something about the collaborative nature and the ever-changing musical partnerships that were formed, disbanded, mutated, etc., really challenged the centrality of the musician, band and song.

Something else that I was really interested in was how improvised music de-emphasizes the individual, or at least sets the self in a really interesting relationship with the other collaborators. Because there are no established roles for each musician to perform, the assumptions about how the self and the group work independently and together seem very different than in traditional composed musics. There was so much to be understood about selfhood and grouphood in this context.

I always thought collaborative improvised music was a really interesting place to examine the history of the ego in art. I know that “experimental” music from the 60’s was very much into eradicating the ego, removing the expressionistic and subjective from sound—and to a certain extent this is what really attracted me to improvised music when I got started. Today, I think about it differently. My sense is that the practice of improvising is about the self in tandem with collective identity. I think an individual self, and not just their musical self, but their self-self, can be both influenced by the improvised music collaboration and also insert that identity back into the music—almost as if one’s identity becomes a compositional strategy. I see a lot of benefit in the individual performing their idiosyncratic self within an improvised music collaboration.

Also I get a lot of joy in exploring the free form, indeterminate and not pre-defined shapes of my collaborative improvised music as a way of understanding of my non-white, female identity.

KH: Yeah it’s totally fluid…

BJ: I think that’s why I felt it was radical because it was a music that felt as fluid as the fluidity of my identity.

KH: Totally. There are many dominant structures that exist that are, like most aspects of our society, made for a certain people, and if your identity doesn’t fit into this rigid standard, well you might not as easily fit because it’s not really made for you anyways.

BJ: I can’t imagine trying to be a classical musician or trying to make rock music, trying to build towards the value systems of those genres. They always felt too specific, too rooted in particular people, places and ideas that didn’t always resonate with my own idiosyncratic self. Not to say they didn’t influence me and drive my musical development, and not to say I don’t like a lot of different kinds of music, but improvisation as a practice gave me a chance to play with those forms both as disruption and a homage. It allowed me to hack the code of genre with the idiosyncrasy of self. To be honest, sometimes being yourself in this way, inside of art-making, can feel very radical.

I get a lot of joy in exploring the free form, indeterminate and not pre-defined shapes of my collaborative improvised music as a way of understanding of my non-white, female identity.

KH: And it’s super connected to who you are.

BJ: Yea, it feels connected because the process of playing music in that way is much more tied to a process of self-understanding. Making the music becomes the same thing as understanding what the music wants to be.

KH: One of the reasons I wanted to talk to you was because something about your approach, as I’ve understood it, feels disruptive, as you say, to traditional power structures. I think it’s something that I sense in what you produce but also in your other projects like TECHNE and your curatorial type of work.

BJ: I think the things that really disrupt power structures are being reminded of the totality of the existence of things you don’t know anything about. The things you have no clue about can be very humbling. I usually find that people who aren’t in power are more curious or more interested in change. For people in power, the unknown is the thing that is the most fearful, it threatens the stability of their position, possibly the validity of their existence. Which kind of proves that those people in power tend to have a superstructure that makes them feel as if whatever they know is the actual reality of all places and all people.

If my creative work disrupts power structures, it’s probably somewhat inadvertent. What is intentional with my organization TECHNE though, is making situations where people’s reality comes at you, versus your reality at them. Technically, I’m not making space for anybody, everybody is there, but I have to lessen how much space I take up in order to let someone else’s reality come at me a little bit more.

KH: Is that an approach that could also be applied to collaboration more broadly? Are there other ideas that guide your approach within TECHNE?

BJ: Yea, I think that’s a good way of working in general, both creatively and educationally. With TECHNE, I’m asking myself, “What am I doing in this room? Who are these kids? What kind of service am I doing? What kind of presumptions are being made about who they are or what they know? Or what they don’t know? How do I make sure I’m short circuiting that, changing that?” We can’t make presumptions about other people no matter how much we want to. You just have to see, hear and listen to who they are, meet them on that level; say this is your world, and my world and maybe we can have a conversation.

KH: That’s beautiful. I think one of the struggles that immigrants face (and is one of the driving principles of institutionalized racism); is having to show the world that actually, big surprise, but you are a complex human being like everyone else.

BJ: I will say that I’m an unusual type of immigrant because though, I am ethnically Korean, I was adopted by a white family. I do have two other adopted sisters who are also non-white, as well as three white brothers and two white parents. So it’s a transracial adoption situation—something that was really common after the end of the Korean War. It’s interesting, because I can definitely see the privilege of growing up in what was a white American family in cultural and economic senses, though of course, race dynamics within my own family were definitely complicated. However, when I go out into the world, I am not a white person. I mean, I can’t pull that off no matter what my family background is.

In the US, non-white folks are reducible, one-dimensional, without the privilege of full human subjectivity. Often, they are assumed to not have lived the complex beauty of human experience simply because they don’t speak English or are not white. Our country has created this situation. Our media provides very narrow representations of different kinds of people. Our liberal education often represents only certain subjectivities and not others in the art, literature, music, history, science and politics, we study, we absorb, we align ourselves with.

Something I’ve been thinking about a lot is what tools can we use to remind people that human lives are very similar in so many ways—the way we experience loss, joy, pain, confusion—these are all so similar and part of being human. Individual experience may differ but we are all very complicated and unique subjectivities. We are the full range of human consciousness! We are all humans!

Individual experience may differ but we are all very complicated and unique subjectivities. We are the full range of human consciousness! We are all humans!

KH: You have a background in English and writing so I wanted to ask you about how that influences or plays a role in your work.

BJ: When I was a kid, I was always really into reading. Language was something that came easy to me. I talked A LOT, like incessantly, often to myself, I liked writing, I liked thinking about my experience of the world through words. I didn’t learn about Korean language until I was in my 20’s—so English is my first and native language.

KH: Do you think the language(s) we speak play a role in defining our identities?

BJ: We assume that language is somehow innocent, but in learning a language we are being conditioned to communicate things in a “right” or “wrong” way. There’s a value system to how you speak a language and how you present yourself in that language. I don’t think language is about expressing some authentic self, rather, I think the language is often teaching you who you are to be—it has a lot of agency.

Which is why music is so important to me. When I was living in Korea in 2014, I played a lot of music with different collaborators and I rarely spoke that much English. Actually, since I wasn’t fluent in Korean, I rarely spoke at all in Korea. When I came back from that trip I started writing these prose poems about Korea, my grandmother, about the future and the past—if they were the same thing, and I realized I was also writing about my feeling that the English language had led me astray from myself in some ways. I thought, what if the vibrations of the Korean language had resided in my body for 27 years instead of the vibrations of English? How different would I be? Would I be more myself?

During grad school I learned about the design of the Korean script hangul, which is completely fascinating. It’s really like no other writing script. It uses what they call a featural alphabet, which means that it attempts to visually represent the sounds of the language. You could completely map out all of the different alphabet characters in the throat, mouth, lip, tongue, etc. It is truly an alphabet that is intrinsically tied to sound and body. I always thought that was so fascinating—that hangul was designed to make the body make meaning in a very specific way.

Language is more than just an outward tool—it has a lot of impact on your body. There was something interesting about wrestling with that feeling in Korea while I was taking a break from English. It’s like you are a different person in a different language. You might even be a different person with the same language in a different place.

KH: Totally. Language is much more than just verbal communication, but even within just verbal communication there are so many variables and nuances depending on where and how you learn the language. There are so many different modes and versions of English, just depending on the context and culture you learn it within.

BJ: And those different versions, no matter how fluent you are, are used to judge you against the standard of US English. So even within the same fluent language space—there’s a xenophobia built into US English—ways to notice if you’re “not from here.” I think a lot about how Americans judge intelligence, experience, aptitude based on the way a person speaks English. The way that language is used to make decisions about you, your access, your ability to take care of yourself or your family, your safety… it’s pretty fucked.

Sometimes I’m glad that I started getting into music because it offers some relief from how tricky it is to spend all of your time from thinking about language. I feel like I learned an entirely different way of being through music.

Language is used to make decisions about you, your access, your ability to take care of yourself or your family, your safety…

KH: What’s the all girls learning environments like with TECHNE?

BJ: The thing that I found to be useful about an all girls workshop environment, especially with the high school and middle school ages, is that the conditioning around how women are around men, even taking sexuality out of the equation, rather the general cultural conditioning that comes from media, school, peers, family, etc; all that stuff changes how these young girls interact with technology.

I mean there’s other power dynamics, race and class dimensions, and a lot of other stuff going on, but that kind of kneejerk conditioning that leads girls to look towards a male to know what to do, or even just this silent censorship to stop girls from saying what they want or asking what they want to ask. I notice that even just one guy in the room can shift the way that the girls are in that room. I’ve seen this time and time again, and I always find it really amazing and curious how easy it is to change the dynamic by just having it be all women. That it really allows something totally different to happen.

When people say to me, “Why have a workshop just for girls?” it’s because those spaces have so much possibility for difference and seeing yourself differently. Whatever you need to do in this classroom, you are capable of doing it and you don’t have to think about anything else, or at the very least any gender stuff that gets embedded into technology classrooms. Because the project of building a contact microphone itself is almost always new to everyone in the workshop, there’s usually no natural assumption that we’re supposed to have this specific expertise, it can sort of un-gender the experience of working with technology. There is something very necessary about self-sameness in certain contexts that allow women to talk about or have certain experiences while having a level of ease so that you’re not spending all of your time being triggered by things.

KH: I’d love to hear about your time in Baltimore and your experience of it over the past years that you’ve been here.

BJ: So I’ve been in Baltimore for 17 years, and I remember thinking about this when I had been in Baltimore for just a couple of years; the thing I found so important about Baltimore is that it feels like a city that lives on the surface. It’s pretty porous in a lot of ways. All the permutations of human existence are right there, visible. It’s a really transparent city in that way.

I think people who live here for a while become the types of people who have a hard time pretending that things outside of their experience and understanding don’t exist, don’t’ impact them every day. You just can’t do that so you just don’t. And so there’s a groundedness to not pretending that I think is extraordinary. Obviously, it’s not valuable to have violence, racism, crime and regret, and that’s not a situation that anyone wants, but it does produce something that other cities often don’t have, an extraordinary resilience.

I saw this resilience a lot during the Baltimore Uprising. There’s something to be said about the fact that Marilyn Mosby and Baltimore filed criminal charges against cops when Ferguson and NYC had failed to do so. And that after the Uprising, I heard so many stories about folks going out into communities and really changing their thinking about their role in that community, how they could help and what it means to do community work in general. I was seeing a lot of difference in how Baltimore rebuilt and responded. It felt the way Baltimore often feels to me, raw and humble, angry and productive, truthful and resilient.

KH: Do you think that being an artist here is different from being an artist somewhere else?

BJ: In Baltimore I’ve always experienced that stark reality that reminds me that while arts and culture are great and all—people are dying—nearly every day. And I think that does have an impact on artists in this city. I don’t have a lot of pretense of specialness or superiority in what I’m doing as an artist. Growing my creative life in Baltimore really changed what I saw as the artist’s role. I mean, I make my work and I want to be successful at it, and I have extremely high aesthetic standards and aspirations, but at the same time, I have to be a person that is doing something, I feel like I can’t just see the artwork as the artwork, if you know what I mean?

Ever since grad school I’ve been trying to answer the question, “What’s the point of being an artist?” I do think that artists have the capacity to present difference in experience, which I think is a vital way to actually change oppressive power dynamics. So artists have the ability to do that if they’re given space to do that, and to project different experiences out into the world and have them received. But the other part of my art practice is acknowledging its role in understanding myself. I think about what Ralph Ellison’s character in the Invisible Man says, “When I discover who I am, I’ll be free.” So that’s something important to me; self-understanding = art practice = freedom. All the things I do, curating, organizing, teaching—I’m learning how to be free.

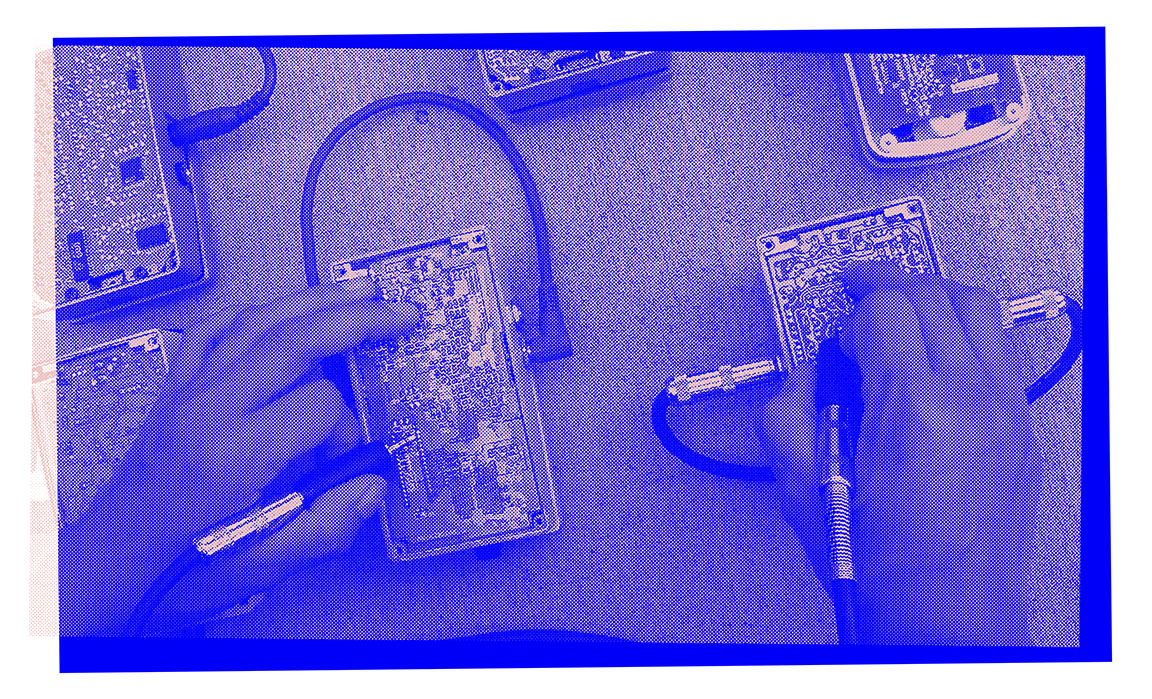

Improvised music making had such a key role in that process—because it’s intuitive and collaborative and it’s about throwing out any preconceptions about stuff. My electronic instruments are so unusual to begin with, so it’s about interacting with an object in such a way that the process of interacting with an object is the process of understanding your music, and is the process of understanding yourself all at the same time. Improvised music coming from wherever it’s coming from, it’s just expressions of different ways of being in the world…

KH: What do you say 100% yes to?

BJ: 1. 100% yes to validating and giving shape and reality to anything that I encounter that I don’t know or understand. If I don’t know it? It’s bigger than me..? 100% yes. You don’t necessarily need to learn it, I mean sometimes people learn things in order to control them. So I don’t even need to learn it to say yes to it.

2. 100% yes to, finding non-verbal ways to inhabit other experiences. Music was the one that I picked.

3. 100% yes to completely re-configuring anything that you think is a “canon,” or to anybody who wants to completely change the idea of what should be learned in the history of art, for example. Essentially what I’m saying 100% yes to is fucking up history.

4. I definitely say 100% yes to Korean BBQ. I could totally eat that right now!

5. 100% Yes to young people kicking ass and using their privilege, power and skills to do bad ass creative and social projects!

About If I Ruled The World: Presented by Press Press with support from BmoreArt, If I Ruled The World is a publication that takes inspiration from the Nas classic, “If I Ruled The World” (It Was Written, 1996), in order to facilitate artistic collaborations and conversations between a range of Baltimore-based Creatives and activists. In their responses, contributors present their most positive visions of the world, and by doing so are able to thoughtfully analyze and investigate the nuances within the struggle for equity in our city and the active role of artist within the pursuit for social change. If I Ruled The World is curated by Kimi Hanauer with direction by contributors and the Press Press team.