IF WE SAY THESE THINGS GO TOGETHER, AND THEY ARE GOING TOGETHER, THEN THEY MUST GO TOGETHER! A Conversation with Katie Khatib

By Kimi Hanauer

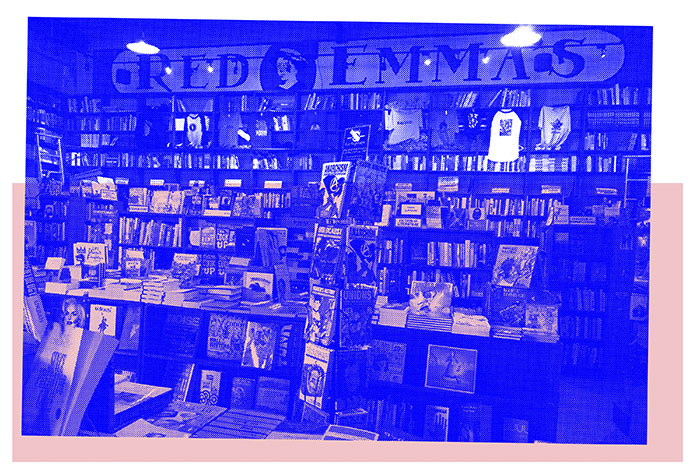

Kate Khatib is a co-founder and a current worker owner at Red Emma’s, a cooperatively owned and operated bookstore, restaurant and events space on North Avenue in Baltimore. A former member of the AK Press collective, she has a PhD from Johns Hopkins and occasionally leads Right to the City bus tours, when she’s not busy mentoring emerging coops and building community-controlled capital pools to support worker-owned businesses.

Kate Khatib: One of the things that I think that is interesting that came up a few times throughout this project is humor. I came into politics through Surrealism, and that’s a big part of American Surrealism, specifically; the way that we use humor and cultural forms, and the way that poetry itself, can be forms of resistance. This project speaks to this question of, why make it so multi-faceted? Why bring in so many different elements? I think that’s one of the things that is potentially revolutionary about it; the fact that it can transcend the boundaries of one medium.

Kimi Hanauer: We didn’t want to limit the ways in which people could participate or the form they could participate through. There are obvious constraints of course, but opening it up as much as possible was one of the things I really tried to do. What your saying reminds me of my conversation with Bonnie Jones, where she talked a lot about how poetry is really good at confusing power through language.

KK: Language is one of the most powerful and terrifying realms that we have available to us. It’s interesting because there’s this question of freedom that runs through this project as a thread, and one of the things that I’ve been thinking about lately, which I feel has some relevance here, is this notion that sometimes the most powerful act is the refusal to engage on someone else’s terms.

That came up for me because one of the things that we’ve been thinking through at Red Emma’s; how we want to interact with people around the language that they use to talk to us and about us. Because we are a collective that has a lot of folks coming from different and many historically marginalized communities—folks who have traditionally been denied a voice in a lot of different contexts—one of the things we’re dealing with now, is working on creating a space where we are able to define the way we are talked about and how we talk about each other.

That’s not something that can really be done easily when you run a public space that has a lot of people going through it. So that’s something that we’ve been talking about—do you always have to engage? Or sometimes is it more powerful to simply refuse to engage?

KH: It’s a way of taking back the power in that situation. Bryanna Jenkins also talked about that in this project; about how there is power in who and to what you answer to.

KK: Exactly. One of the things that we have to remind ourselves is that we don’t always have to answer to everyone. We can always say this is not a conversation we are interested in having.

KH: Yeah. When thinking about creating “safe” public spaces that are open and tolerant, the question that comes up for me is at what point do you say no? Being accepting and tolerant can also mean being accepting of things that are fucked up in all sorts of ways. So how do you know where to draw the line?

KK: I think it’s the critical question we always come back to. When you talk about creating spaces that are free and safe, there’s this one little problematic note that you always forget to sound; that a safe space to one person isn’t the same to someone else. The things that one person might need to feel ok, to feel like they have power and respect, is sometimes totally antithetical to what someone else might need. I think it’s a constant negotiation that takes a lot of time and it takes a lot of energy. This is something I was thinking about before this conversation, that, if I ruled the world, my vision for the world is that nobody rules it.

It’s that we manage to create structures that are both freeing and collaborative at the same time. But I always come back to this notion of how do you negotiate that contradiction? How do you build structures that create space for everyone to feel safe and start working towards building shared languages; while understanding at the same time, that if we are demanding that everyone uses the same language, we are also limiting people’s ability to express themselves in a manner that feels most comfortable to them. It’s really difficult and it’s the central question we have to figure out as we work towards envisioning what a truly just environment in our world would look like.

KH: The first time I spoke to Jared Brown about the idea of this project, he said to me something like, “I love this song because it makes me feel like I have the right to think about if I ruled the world.” So, in one sense, it’s this really powerful thing because it can redistribute power in this way, but it’s also so egotistical. Another one of the tying threads throughout the work is a conversation around trying to find a way to reframe the question itself and create a contemporary version of it…

KK: What’s interesting is, I was looking at the manifesto for human rights by the Refugee Youth Project students, which I think is really cool, but what’s totally fascinating is this line “The president cannot act without the people!” And part of my response to that is, well, do we need a president? I know this was produced with young folks who are just starting to think through these contradictions, but for me, I think about how can we change our thinking enough so that we stop even thinking in these structures? It’s not just that the president needs to answer to the people, but actually that is an antiquated idea. We have to conceptualize more contemporary forms of self and of governance. Maybe a good question for you is, other than wanting to think through this idea, what are you hoping this project is going to do?

The things that one person might need to feel ok, to feel like they have power and respect, is sometimes totally antithetical to what someone else might need.

KH: I think a lot of this has been intuitive. I think that imagination and art and positive thinking are powerful. And I think that by asking people these questions, it’s another way of reminding someone that they are powerful and can take up space and think about such broad things as the fate of the world. I don’t know what this project really aims to do specifically, but I think that when things are difficult, as they always are, that’s maybe just what you have to do, imagine new ways of being. I think I also just didn’t want to be alone in my imagination, I wanted to talk to people and think through what things could be like together.

KK: There’s certainly something to be said about, well, you can’t change the world if you don’t know what you want the world to look like.

KH: Yeah, and you can’t know what you want it to look like by yourself. Which is why the collaborative aspect of this project felt so important.

KK: But at the same time, I think this work is not just directed at the folks involved in producing it. This project has this very public aspect. It feels like it tries to reach as many people as possible with all of these different forms. So assuming everyone in Baltimore, one way or another, comes into contact with this project, what’s the potential impact?

KH: Maybe just more people imagining the world as it could potentially be.

KK: I like the fact that there are so many contradictions in this work. I think that’s one of the things I like about multi-media work, is that it does kind of play in contradictions; it brings together all of these different mediums, a collage of images and materials that don’t really go together, but by virtue of the fact that you put them all in the same place, then they must go together. Which is maybe calling back this thing about Besan’s Freedom Printer; if we say that these things go together, and they are going together, then they must go together. (“If we say we are printing our freedom, and it’s happening now, then that’s what’s happening!”)

KH: Yeah, it’s like the poetry again. It’s confusing the standard rules of a type of language.

KK: For sure, poetry is one of these interesting things. Because it depends on what kind of poetry. Some poetry is all about just finding freedom in structure, but at the same time we also think of free verse as poetry. Poetry is a place to redefine rules and redefine the structure of language in the way that we find most inspiring. So poetry itself is a kind of contradiction. The surrealists were so enamored by the idea of poetry as revolution and revolution as poetry, which I think opened up these new spaces for understanding the world that we live in.

KH: I’m still trying to think about, what it means to ask someone some of these questions, like what makes you feel free? And what brings you joy? I didn’t really have a specific intention in mind when that started, but they were both themes that came up in initial conversations surrounding the project. Often it felt like this is just what we wanted to be talking about and something we needed to be asking one another.

KK: Just thinking about the Baltimore context, I think those sound like questions that we need right now. What’s happened in Baltimore for the past year, is the result of a much much longer process of systemic oppression and devaluing of human life, on the basis of racial and economic factors. But even understanding that everything that’s happened this year, exists in a much, much larger context, it’s been a hard year for Baltimore.

It’s been an exciting year in some ways, but it’s also been a terrifying year in the sense that everything changed and nothing changed. So maybe there is some power in just asking those questions, in opening the space up and just about reminding people that they do have the power to think about what a different world would look like. I think that’s what the Uprising was about. It reminded us that we do have the power to speak out, that we do have the power to demand a change.

Even though demanding doesn’t necessarily achieve that change. We made some small gains but there’s so much more work ahead of us. So much of that work has to be done by people who have been denied their basic human right to existence. It’s sometimes inconceivable how we might possibly continue with this work, but at that same time, I feel like there are so many new possible conversations, and so many conversations starting.

One of the most powerful acts is refusing to stay in the box, to stay in the neighborhoods, or in the red lines that have been drawn that tell us where we can and can’t be.

I think the Uprising helped us remember that the things that divide us are largely things that neo-liberal contemporary capitalism puts onto us. I think one of the most powerful acts is refusing to stay in the box, to stay in the neighborhoods, or in the red lines that have been drawn that tell us where we can and can’t be. And that was one of the things that was special about the Uprising; for a minute, it felt like some of those imaginary and invisible lines had actually been erased. I think the question is how do we keep those lines away and banish them for good? And can we actually even do that? And certainly it’s going to take a hell of a lot of imagination and utopian thinking to get us to that point.

I think this project is a step towards that place. It clearly is coming out of some of those same feelings, of maybe this is the time to ask this question and even if the question is problematic, and contradictory and we know that, there is still some power in just asking this question.

KH: So before we finish, I just wanted to ask you some of these things I’ve been asking everyone in the conversations surrounding this project: What if you ruled the world? What brings you joy? What makes you feel free?

KK: I’ve lived in a lot of different places, and Baltimore, for me, is the place in the world that has the greatest sense of possibility. Which is something I’ve felt since I first came here. It’s something so unique about this city. And it’s a very melancholic possibility.

One of the reasons there is so much responsibility is because there is so much abandonment. There is so much of the city that is underappreciated, and underused, and undervalued, and at the same time, there is an incredible resilience here. Every day I see this more and more in the area I’m in constantly, in Station North, which is a nice segway into the question of what makes me feel free, because that is one of the things that’s been most inspiring this past year. Seeing the relationships that we’ve built through this space with the different communities here, and again, it is this reminder to me that there are these very unnatural lines that divide us from one another.

One of the things that we’ve really sought to do is scrub out those lines, and not erase them—I mean you can’t erase the pain and hardship that comes with them, but for me, there is this incredible freedom in walking through a space and seeing art students talking to elderly folks who live in the low income housing, and seeing those folks getting to know just everybody. That, to me, makes me feel free. It reminds me that we have so much power when we are together and when we refuse to be divided.

I think that’s also my vision… A world where we are able to exercise our collective power and we are able to find ways to do it that help us to build shared languages that are truly shared, not just one language that replaces others. That’s thinking of language in the sense of English and French and Spanish, but also in the sense of the words we use, and the way we talk about each other; language in a more broad way of just ways of communication.

***

About If I Ruled The World: Presented by Press Press with support from BmoreArt, If I Ruled The World is a publication that takes inspiration from the Nas classic, “If I Ruled The World” (It Was Written, 1996), in order to facilitate artistic collaborations and conversations between a range of Baltimore-based Creatives and activists. In their responses, contributors present their most positive visions of the world, and by doing so are able to thoughtfully analyze and investigate the nuances within the struggle for equity in our city and the active role of artist within the pursuit for social change. If I Ruled The World is curated by Kimi Hanauer with direction by contributors and the Press Press team.