Marian April Glebes at the BMA, Loading Dock, and Sondheim Semi-Finalists Exhibit

By Amber Eve Anderson

Home, museum, salvaged material re-use center—these are the sites and subjects of Marian April Glebes’ Three Sheds for Three Sites, a triptych of sculptures that explores concepts of mobility and preservation through curated objects in three locations.

“Shed I: Home Shed” is located at the Baltimore Museum of Art where, according to the parenthetical title of the piece, it “performs the functions of home.” “Shed II: Museum Shed” is at the Loading Dock, a salvage material re-use center that partnered with the artist for the piece, where it performs the functions of the museum. The final part, “Shed III: Collection Shed,” is typically located in the artist’s own home but was on view as part of the Sondheim Semi-finalists exhibition at Decker Gallery on MICA’s campus until the end of the July.

A shed is a simple structure whose clear purpose is to store materials, while the home, the museum, and the collection encompass much more abstract notions of functionality, each with its own impetus for preservation and longevity. The titles reiterate the performative and functional aspects of each of the three sheds—each one performing a particular function—giving the work a sort of fluid agency. The fact that each piece is mobile—built on wheels or sitting on top of a pallet jack—reiterates this idea of changeability.

Wheels suggest transience, movement, and lack of permanence. From the personal to the institutional, each shed poses the question: what is worth preserving?

Glebes is a conceptual, multidisciplinary artist whose work addresses materiality and the home in the context of urban environments and one’s relationship with place. At the BMA, “Shed I: Home Shed,” a modular, three-panel piece, sits in the center of a room as part of the Imagining Home exhibition. The structure indicates the potential to collapse and unfold, housing within it all of the elements necessary for a fully functioning home: two folding chairs and a murphy table, a floor lamp fitted into one wall, bookshelves, cupboards, pillows stuffed into a narrow cubby, a shower curtain, a broom and even a house plant, everything painted entirely white.

The uniform white surfaces erase the particularities of any specific home, leaving the non-descript objects to illustrate the functions of a universal home: a utilitarian space for sleeping, cooking, eating and cleaning. The piece recalls the functions of a hotel room more than it does a personal home. In a world in which people move further away and more frequently than ever before, putting down roots is an obstacle. By using the term home as opposed to the word house, the artist suggests that home is a formula for activities.

Two objects in “Shed I” indicate the possibility of something more than mere utility: an empty picture frame and a house plant. These hint at decoration and the instinct to nurture, activities which transform a house into a home. Though these activities make each move heavier and more cumbersome, they provide a buffer to the monotony of white walls and Ikea furniture. In this context, even cooking and cleaning become expressions of individuality and care. Home becomes a repository for actions rather than objects.

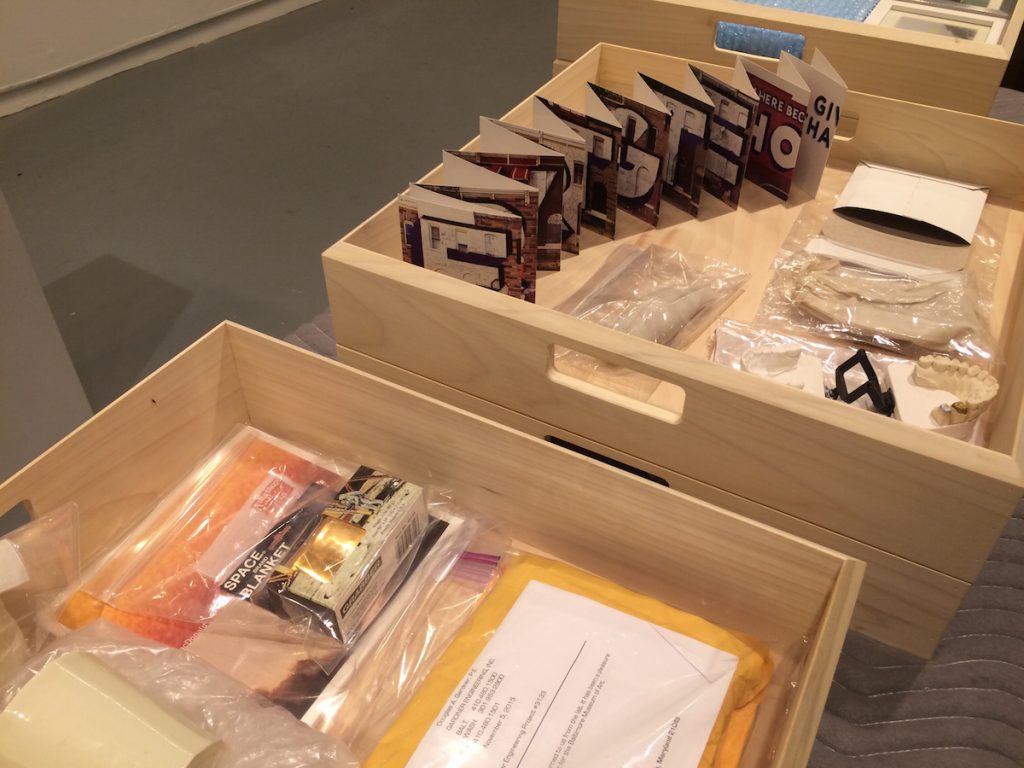

In response, “Shed III: Collection Shed” is a humanizing counterpart. Whereas “I” represents an aestheticized, universal home in a museum setting, “III” acts as a museum collection in the home of the artist. Still mobile, but much more compact, “III” is filled with personal items: a dental mold, a picture frame wrapped in blue bubble wrap, a gold space blanket, ceramic objects and manila envelopes, among other things. All this is housed within a museum-grade, waist-high wooden box, filled with a stack of drawers.

The concept of collecting personal objects is legitimatized through the process of preservation and documentation. The deep, oiled wood of the box and its shelves are fashioned after high-end furniture, though it is hard to imagine this piece blending into a home setting.

In the Sondheim Semi-Finalist exhibition, the lid of the box is propped open next to a worktable topped with a moving blanket and shelves in varying levels of storage and display. Lying inside the uppermost drawer stacked inside the box is a pair of white gloves for handling art objects. Nearby are three pedestals displaying three-dimensional objects, while on the back wall hang a series of objects.

Of the three sheds, this one carries the most nuance, along with the intrigue and particularities of any collection. Though compact, its contents are sprawling, each object seeming to have a story behind its acquisition. In conjunction with “Shed I: Home Shed”, it calls to mind one’s own personal collection of objects and ephemera, the things gifted by loved ones that help to construct a personal history and a sense of self, “…a repository of things whose familiarity and concreteness help organize the consciousness of their owner, directing it into well-worn grooves,” as stated by Mihaly Csikszentimihalyi in “Why We Need Things.” Glimpses of personal exchanges, along with the knowledge that the shed usually resides in the artist’s own home, gives the work a sense of intimacy.

Still, given its usual inaccessibility and the exhibition display, the viewer is at arm’s length. One can’t be entirely sure whether the work is still in the process of being installed or is meant to be viewed as is. This sense of uncertainty makes one approach the work with a certain hesitation, like inspecting the objects of a stranger’s house—objects that aren’t meant to necessarily be looked at. The collection itself becomes more important than the individual objects. Like “Shed I” represents the idea of home, “Shed III” is the idea of a collection in which the acts of curating and documentation are more important than actually viewing it. When our homes become museums to ourselves, what becomes of our objects?

In the midst of discarded stoves, lamps, bookshelves and lights near the entrance of the Loading Dock, “Shed II: Museum Shed” almost disappears in the disarray. Though it is itself a white cube guarded by white traffic cones sitting atop a pallet jack, also painted white, it is as if it’s just another discarded piece of architecture, waiting to be discovered and reused. The cube itself looks the most like a literal shed from the exterior, though small frames and labels hang around the walls. One wall functions as a door to allow a single viewer inside.

Once inside, the perfect walls of a white cube gallery are hung with objects sourced from the Gift Shop of the BMA. The framed postcards and magnets were curated by the artist to reflect themes from the Imagining Home exhibition at the BMA mentioned above. It completes a sort of loop in the trio of sculptures, in which the objects in a museum collection have the potential to become beloved objects in someone’s home.

Magnets and postcards become pocket-sized items worthy of preservation and museum display, a practical mode of collecting in an age of mobility. Although the piece is camouflaged by the store’s surroundings, the dirtied white carpet on the inside of the white cube indicates a multitude of visitors, reiterating traffic and transience, but also bringing to mind the idea of decay, which again loops around the notion of preservation.

The circularity of the work as a whole—a home in a museum, a museum in a salvage re-use materials center, a museum in a home—becomes problematic in terms of accessibility. The parenthetical titles of each piece reiterate the relationship between the three, but it is unlikely that viewers will see all three sculptures. The human-scale of each piece calls attention to the body in relationship to each sculpture—the sheds important not only in and of themselves, but in relation to their site and one’s location at the site when viewing the work.

Given that each shed points to an abstract idea, the conceptual framework becomes that which holds the three pieces together. The work blurs the lines between everyday objects and art, which gives value to actions over objects—the impulse to save and the act of curating. Three Sheds for Three Sites pushes the boundaries of what and where a museum can be while calling into question its role and responsibility.

*****

Author Amber Eve Anderson is a Baltimore-based multidisciplinary artist whose work uses images, objects and language to explore themes of place and displacement. She is a recent graduate of the Mount Royal School of Art MFA program at MICA.

Marian April Glebes “Shed 1: Home Shed” is on exhibit at the BMA in the Imagining Home Exhibition, while Shed II is at the Loading Dock, and Shed III will return to the artist’s home.