Are archives sterile and cold on purpose? My first experience with an archive was through the UMBC Library: I was tasked with finding photos and articles of students from every decade of the school’s existence. An archivist walked me through a small room, taught me how to handle the goods, and gave me a simple cardboard box containing photos of students lounging on the grass where the library now stands.

It meant a lot to me to make connections between the concerns and protests of students 50 years ago in contrast to the present. I was grateful to have more intimate and tangible historical context of their lives. It hurt me to see how little had changed. It’s been said before, but we’ve been dealing with the same shit for so long. I cried a bit and reached up to wipe my tears, only to remember I had on white gloves. My first thought was, “Are they gonna be able to wipe my tears off of these gloves?”

I felt completely okay shedding a few tears in the Dispersive Archives exhibition, on view at Waller Gallery through March 2. A collaboration between writer Lawrence Burney, artist and curator Joy Davis, and archivist Jessica Douglas, Dispersive Archives showcases archival processes for Baltimore-specific stories as vital, intimate, and dynamic.

Davis and Douglas collected books and photos as a part of the larger Dispersive Archives Project, which will take the form of “a digital repository of collected memories sourced by Davis and Douglas,” according to the description. The photos on display ranged from headshots of family members to lively dancing in dim clubs. The books came from Davis’ personal collection, focusing mostly on Black history and critical race theory. During the opening of the exhibition, Douglas sat with many people and listened to their stories on Baltimore. She recorded the stories, intending to preserve them through the project, and will be collecting stories through the end of the exhibit.

The project and the exhibition are dialectical. Davis’ social practice experiment “How to Create an Archive” allows participants to broaden their understanding of what an archive is. A questionnaire, which visitors are invited to take and answer themselves, asks various things like “What is your biggest triumph?” and “Where were you born?” The questionnaire disarms the viewer and leads them to think more empathetically about interviews. Accompanying the questionnaire is a seven-step guide that places no limits on what can be included in an archive, or the form that an archive can take.

“How to Create an Archive,” Joy Davis. (Photo by Cara Ober)

“How to Create an Archive,” Joy Davis. (Photo by Cara Ober)

Lawrence Burney’s work in the Dispersive Archives show connects the intimacy of Davis’ and Douglas’ work with powerful visuals. Using archival footage and photographs (sourced from family and friends with tapes of old news broadcasts, and the internet), and with assistance from artist Kyle Yearwood, Burney preserves Baltimore memories as precious records of local icons, cultures, and events—such as arabbers, the Block, K-Swift and others—that only a Baltimorean would handle with as much care.

A journalist, editor, and native Baltimorean, Burney says his work in this show has taken years to complete. When someone pulls an archive based on their intimate knowledge, they are able to piece together stories with fewer gaps. Their community is also invested in the archival footage and how it’s curated. There’s a commitment to honoring the people and the city. The types of footage in Burney’s works range from formal documentary interviews to YouTube videos of rapper Lor Scoota with his friends.

Much of the footage Burney collected feels deeply nostalgic and familiar. In his piece “We can’t let them take all this shit,” a woman talks about how the AFRAM festival was fun for her family and a great way to support Black businesses. In 2018, the AFRAM festival was cut down from a two-day festival at Camden Yards to a single-day festival at Druid Hill Park. When Mayor Pugh announced her decision, I was worried that AFRAM would go the way of the Stone Soul Picnic, a festival in Druid Hill Park that went on for 20 years and hosted acts like Jazmine Sullivan and Mary J. Blige until it ended in 2012 without much explanation.

I was concerned that the one weekend that Black people could be out in the sun—because we know it’s anti-Black to have those babies out there for MLK Day in the freezing cold—in a space that was meant for us would be taken away. In the description for the piece, Burney bemoans that feeling, saying “the poppin festival from your childhood was discontinued and now you sound like an old person telling the kids about how fun it used to be.”

“Roun’ the way: now, then, next,” Lawrence Burney. (Photo courtesy Waller Gallery/Joy Davis)

“Roun’ the way: now, then, next,” Lawrence Burney. (Photo courtesy Waller Gallery/Joy Davis)

Baltimore is Black, it’s been Black, and will be Black. Rarely are there exhibitions that make Baltimore’s Black history their focal point, and that’s because there are few people who can do it well. Baltimore’s history is deeply embedded in the way we move around here, and Baltimore natives rarely get a chance to display their love and knowledge of the city. Often people considered experts on Baltimore are imports from somewhere else. It’s one of the worst things about the city—a byproduct of the racism.

But Burney puts on for Baltimore’s beauty and talent like few others do, from his zine and radio show True Laurels to his work as a senior editor at The Fader. In his piece “Come out front and look at this, they really draggin’ forreal” Burney digs into the depths of Baltimore music, like Baltimore club and Lor Scoota on the street with his boys hyping him up. There is a distinct rebellion in this collection. In the description for this piece, Burney notes that there is a belief that Baltimore artists have been purposefully excluded from the national music scene.

After seeing the videos Burney put together, I believe that many people in the national music scene truly could never appreciate what Baltimore brings to the table. Baltimore doesn’t spare feelings. You’ve never been roasted until you’ve been roasted by someone from Baltimore and the rest of the country can’t always vibe with that. Living here most of my life (for I, too, am an import) has given me thick skin and a brazenness that doesn’t translate when I go back to see my family. I have shown people around Baltimore only for them to say things like “Why is everyone so mean here?” Where they see mean, I see people who don’t listen to any bullshit and aren’t afraid to call it out. There’s a lot of bullshit in music and people who call it out don’t get famous.

In that video, Keys, a Baltimore rapper from Poplar Grove and Edmondson who faded away after her 2010 track “Go Off,” raps over Nicki Minaj’s “Itty Bitty Piggy” track basically saying she was already tired of Nicki (and we know “Itty Bitty Piggy” featured some of Nicki’s best bars to date). This clip made me realize why we need archives that focus on joy and the daily lives of Baltimoreans. I don’t actually care what Baltimore looked like in the 1800s.

I have never once sat on Federal Hill and thought wistfully about Francis Scott Key, never been to Fort McHenry. I care about where all the Black people used to party; I care about how the arabbers learned to sing.

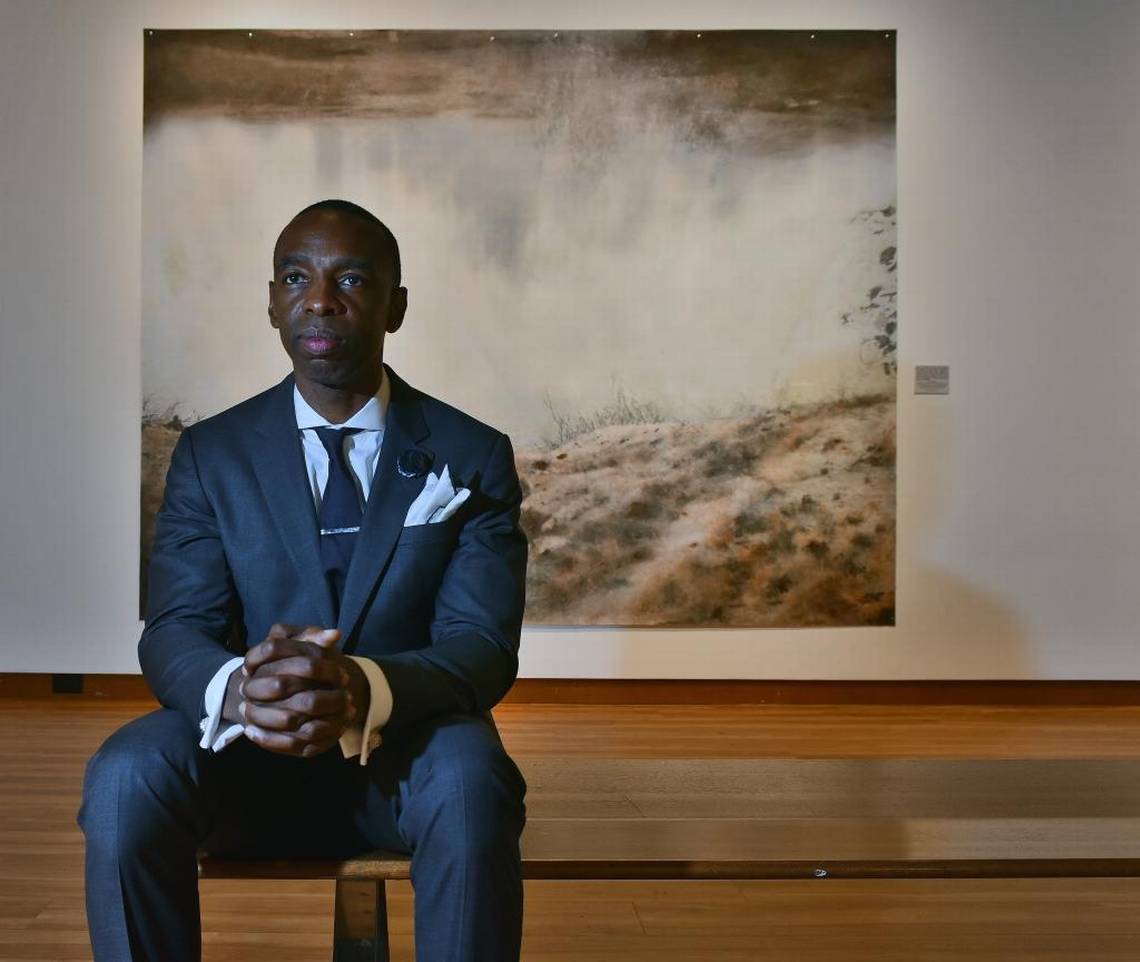

Dispersive Archives is on display at Waller Gallery through March 2. For more info, visit wallergallery.com. Featured image courtesy Waller Gallery/Joy Davis.