I was talking to a single friend the other day who told me it is no longer okay to meet a potential partner in a bar, in an elevator, on the street, or anywhere random. This is now considered sketchy. However, it’s perfectly fine to meet strangers on the internet, text them intimate secrets and photos of your junk within a few days, and then schedule a first Netflix-and-chill non-date at their home and expect sex.

The new rules around finding romance, connection, and meaning sound absurd to me, not just in their complete lack of spontaneity, potential for false impressions, and arbitrary personal boundaries, but also in their limited effectiveness. Falling in love requires mystery, chance, trust, and instinct. Sure, a text message from a certain someone can make you feel a surge of dopamine, in that you’ve captured their attention for a second, but then you immediately want more. This is junk food. This is addiction. This is not healthy or real.

It occurred to me that the same new “rules” destroying dating are similar to the prescriptive directives for connecting with a work of art. Due to insularity, technology, the art market, and a majority of writing about art, we now carry a bevy preconceived notions about the kind of art we are supposed to love, how to love it, and how it’s supposed to make us feel.

The potential for shame around who has taste and who doesn’t, the entrenched boundaries between high and low art, and the intellectualism around a mostly non-verbal process has rendered the experience of careful looking clunky and complicated and—most importantly—ineffective. There’s so much pressure to get the inside art-world joke, to explain the conceptual theory, to share the sensitive anecdote, and many of us simply do not have the education, connections, or time for this. All these extraneous demands and boundaries, designed to intellectually legitimize and financially boost a work of art, are not particularly necessary for the majority of potential art lovers who wish to simply look and think and react. As a result, all the baggage around visual art mostly makes people feel inadequate, dumb, and unworthy, hindering an experience that was once a direct line of visual communication between artist and viewer, sensation and feeling.

In reality, art is everywhere. Whether architecture, fashion, food, film, music, or visual art, being open to the possibility of finding it at all times and in all places increases your chances in finding your art—that is, the art that is meaningful to you and has the power to change your life. The best art reflects essential wisdom about living a meaningful life, that is, the pursuit of love, purpose, connection, and creativity. In the same way that modern dating practices are being altered by technology, money, ambition, and the desire to insulate ourselves from uncomfortable feelings, our ability to experience art in a direct way has been largely sidelined. As a result, many of us are missing out on valuable experiences.

I tend to use a lot of dating analogies when talking about art. Just like meeting that special someone, a powerful work of art elicits an exhilarating, immediate, mysterious, and physical response. If it’s not sexy, you’re doing it wrong. I have compiled a few strategies to help make your experience of art more pleasurable, and who knows? Maybe this will spruce up your love life, too.

Andy Warhol, “I Love You SO,” c.1958 (angel)

Andy Warhol, “I Love You SO,” c.1958 (angel)

The Problem With Screens

In these modern times, the first place where we experience a piece of art (or a potential mate) is on a screen. Great works of art can look impressive in this format, but often do not. Sometimes they require a skilled photographer to capture them in exactly the right way and other times they are impossible to capture in a photo. The bottom line is that looking impressive on the Internet does not correlate with a great in-person experience.

Like the out of date pictures often used in dating profiles, the art that looks best on a screen can often be a disappointment when experienced in real life (IRL). This kind of art is flourishing right now on Instagram and Artsy, etc. and some artists are strategically creating work specifically to be experienced on a screen and sold online, but this is often a letdown in person. It’s a lackluster one-night stand that will not lead to a follow up text. It’s a shallow dive into what should be a deep and rich and disorienting and transformational experience, but feels more like visiting a financial planner.

A screen offers comfort through distance, curation, and editing, but it is a barrier. It is not an accurate indicator of quality, connection, or staying power. A screen is a tool for research, an introduction, but it is never a substitute for the real thing. Art is meant to be properly experienced in person, so it’s essential to be completely present IRL with what’s in front of you.

The author and a friend with Robert Indiana, “Love,” 1973, at SFMOMA

The author and a friend with Robert Indiana, “Love,” 1973, at SFMOMA

The Long View vs. the Close-Up

Like a stranger whose bedroom eyes beckon from across a room, the best works of art possess a curious magnetism. The long view offers a sense of inevitability, and the promise of learning more is intoxicating, but its purpose is to draw you in closer.

Sometimes a person appears handsome and charismatic from a distance, but is a disappointment up close, especially after the harsh house lights come up on the dance floor and the buzz wears off. This might have nothing to do with their physical appearance and be impossible to put into words, but you know something is not good. Maybe they’re blurry or they smell weird or they make a face that reminds you of someone awful. Words sound weird coming out of their mouth and you cannot picture them in your bed. There’s a certain something you cannot quite elucidate, but it’s real and tangible. This is fine. You have to give yourself permission to trust your instincts and to know that all kinds of reactions are valid.

For a work of art to be truly lovable, you have to get close enough to smell it, for it to fill your entire field of vision so that your retinas absorb it all. It is only at this intimate physical level, essentially the same proximity of the artist to the art when they made the piece, where the work can sweep you off your feet. The element of surprise and magic, of defying expectations, is essential.

A work of art either rewards you up close with beautiful detail, exquisite texture, a tangible sense of spirit, and a reflection of your best self, or it’s a dud. Either your heart surges and you need to know more or something is missing and no amount of wishful imagining will make it so. The close-up is the deal-breaker because to be in love, you have to feel a fierce intimacy and magical connection. You should never settle. If the close-up view does not match its impressive appearance from a distance, keep on walking.

Jim Dine, “The Pale Blue Line,” 2014, Woodcut, collograph and copperplate etching

Jim Dine, “The Pale Blue Line,” 2014, Woodcut, collograph and copperplate etching

The Message is in the Materials

Do you love color-saturated video works installed across multiple screens in a dark and cinematic space? Does the yummy surface of an oil painting make you salivate? Do quilts and fiber works melt your heart because your grandmother taught you to do this work with her when you were a child? Your personal experience with materials is relevant. The feelings and familiarity that materials bring to you is the most direct way to connect with a work of art—and I believe you can fall deeply in love sometimes without knowing anything about the artist’s concept, ideas, or biography. Those aspects of the work are useful too, but, bottom line, works of art are objects imbued with an artist’s spirit, and their craft is synonymous with their meaning and power.

Style and appearance, like the materials selected to build a work of art, are purposeful declarations and should not be dismissed in favor of conceptual, intellectual, or biographical posturing. These elements are also important, but let’s face it—at this point in the exchange, you’re already a little infatuated or you’re not. No amount of intellectual banter is going to seal the deal.

An artist’s choice in materials might be made out of habit, inspiration, or access. An artist may choose materials based on their intense love for certain traditions, education, an infatuation built through discovery and experimentation, for the range of possibilities of expression a certain material offers. Or, an artist might choose their materials based on the unique history and traditions around that specific material, otherwise known as material culture, in order to build upon those traditions or to challenge them.

Material culture is political and personal, and the media an artist selects plays a huge role in the meaning of the work. Materials are often not addressed adequately in gallery wall text, which tends to focus on the artist’s ideas or biography, because it seems like such a simple or obvious quality. It might seem superficial, like judging a date by their too-clean or too-dirty sneakers, but physicality and materials form the basis of communication, and are the most accessible route to a connection with a work of art.

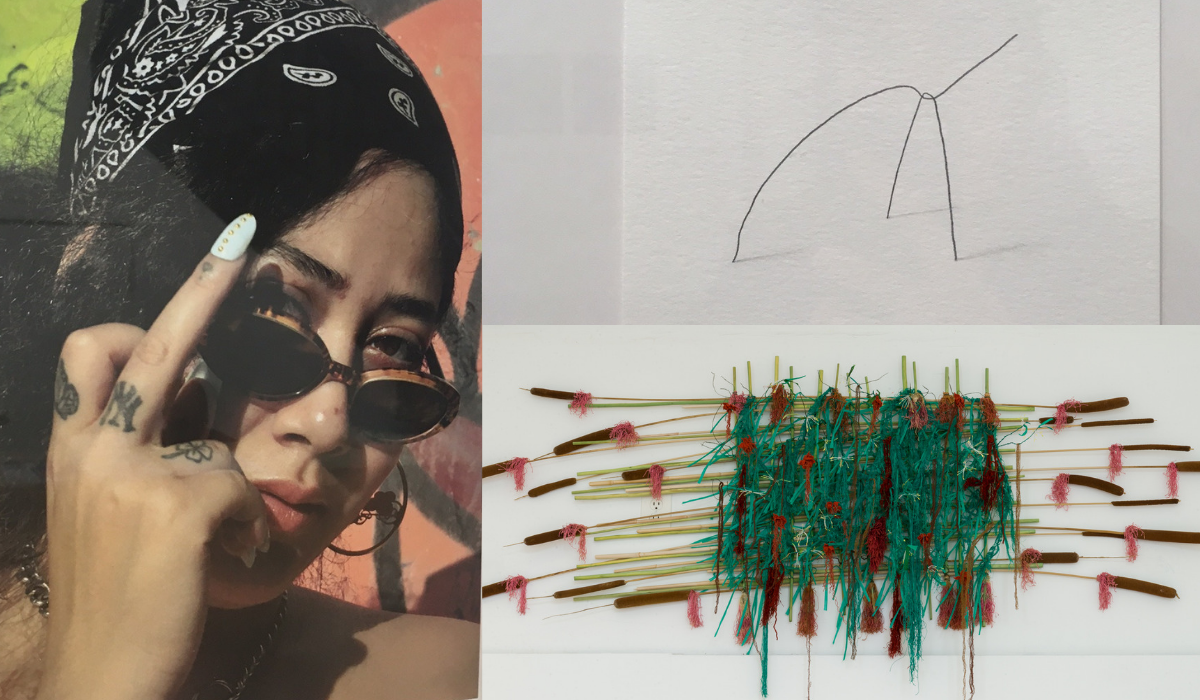

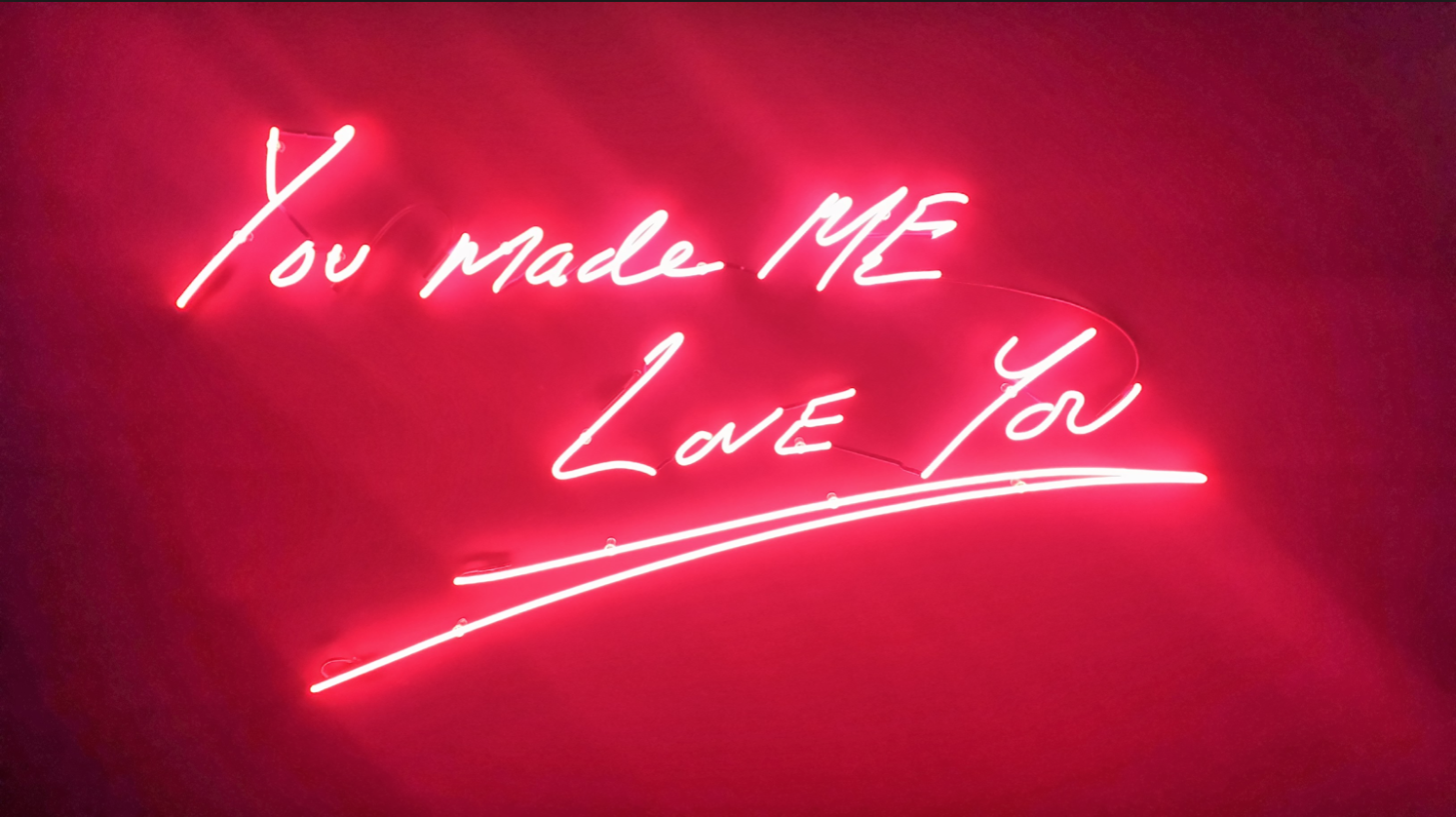

Tracy Emin, “Love is What You Want,” 2015, (Neon) Offset Lithograph

Tracy Emin, “Love is What You Want,” 2015, (Neon) Offset Lithograph

Wow.

I always appreciate it when a work of art completely flummoxes me and scrambles my brain. This happens most often when I cannot fathom how a particular work was created, how a certain unexpected effect was achieved, or how a work has acquired such a unique combination of intriguing characteristics. It does not happen a lot, but when it does, it’s the best. Sometimes, the wow is achieved by awe-inspiring amounts of labor, where incredibly lavish and detailed works make your brain and fingers ache to even consider the number of hours, weeks, and years they spent in creation. Sometimes a work of art appears to be so magically and meticulously created, it seems like there is no way a human being could have accomplished such a feat. Other times, a wow is generated by an artist’s ability to elicit a brand new effect from a traditionally used material, especially when they upend the art world’s long established expectations or hierarchies, like when certain artistic processes are deemed more valuable than others, or where certain practices and crafts have not been considered to be “real” art—and the artist nails it, proving that this long-held assumption was wrong.

Either way, it’s a delightful experience to be wowed by a work of art, just like finding a connection with a brilliant and beautiful human being. Although impressive, the wow should never be intimidating or used to make you feel smaller. Rather, it should give you the motivation to ask questions, to move in closer, to learn more and more. Rather than having a cynical, unemotional, or intellectual response, it’s important to allow yourself to feel vulnerable and bring your own expectations to the experience rather than insulating yourself from possibly feeling or looking dumb.

Frida Kahlo, “Diego on my mind (Self-portrait as Tehuana),” 1943 (detail)

Frida Kahlo, “Diego on my mind (Self-portrait as Tehuana),” 1943 (detail)

Feeling all the Feelings

When you encounter a potential dating partner or a work of art, do you feel welcomed and accepted as you are? Does the work give you permission to be the person you secretly wish to be? Does it make you feel more connected to others, to yourself, to the world around you? Does it make you feel a sense of hope and possibility and faith in humankind’s best characteristics? Or do you feel uninspired and insecure? Do you feel nothing? Do you feel a wistful sense of longing, but left out of the conversation? Do you feel pressure to pretend to be different? All these responses are perfectly valid and the sooner that we become aware of them, the more comfortable we will be engaging with art.

It does not necessarily mean you’re going to feel happy in the presence of a sublime work of art. Sometimes an overwhelming sense of tragedy, regret, or great despair in the presence of a truly great work of art is the best possible response. Often times these are the works that stick with me the most, the ones that are simultaneously disturbing, but offer a powerful and overwhelming reaction, somehow great and terrible at the same time.

What If You Don’t Like It?

I look at a lot of art because it is my job, and to be honest–most of the art I see is not particularly interesting to me. I have allowed myself to stop feeling guilty about this, to allow space for questions and a range of reactions including indifference. The reality is I fall in love with very few of the art objects I experience on a daily basis and this is fine.

It’s important to give even the most unexpected suitors a shot, but we should not beat ourselves up if it’s not working. We should never feel guilty for not loving a work of art that someone else, especially someone we respect, has deemed to be great, or force ourselves to admire that which does not speak to us. Art is a personal and subjective experience. There is someone out there for everyone, but we all have our turnoffs. It’s okay for others to love the works that for us are unlovable. You can love a very small amount of the art you see—this is healthy. You can enjoy the experience of not liking a piece of art, too. And you can still love the artist even if you don’t love their work.

Philip Guston, “Couple in Bed,” 1977, Oil on Canvas

Philip Guston, “Couple in Bed,” 1977, Oil on Canvas

Sealing the Deal

When you find this beloved work of art, whether it’s at the Louvre or the local arts council, you should feel a tingling, a catch in your chest, a heightened sense of awareness and wonder. The best works of art take us outside of ourselves and make us feel somehow larger and more powerful, but also more connected and enchanted with the world around us.

When you are in the presence of a great work of art, your endorphins swirl and you feel a surge of emotion; you feel that the logic you previously subscribed to has been kicked aside and that the limits that you had believed to be intractable are now flexible and fluid; there is a new sense of possibility for yourself, for others, for humankind, for the world. You may feel an exchange of energy, as if you are being seen and heard as your best self in the presence of this object, that it’s offering you as much or more than you are offering it.

Even if we cannot afford to buy it, we can hold onto the art we love with the simple phrase: “I love this.” Once a connection is there, once an intimacy is forged, no one can take this powerful relationship away from you. Especially since visiting an art gallery is free and so many museums now offer free admission, the only barrier holding us back from experiencing the transcendent, romantic, and ridiculous feelings inspired by great art is ourselves.

Andy Warhol, “Heart,” ca. 1982, Silkcreen/collage

Andy Warhol, “Heart,” ca. 1982, Silkcreen/collage

We Don’t Choose Who We Love

Notice I have written nothing here about art history, conceptual theory, artist biography, or identity. These issues are all important in fully appreciating and understanding a work of art once you have committed to it, and if sounding smart when you talk about it is a priority for you, they are essential. Art that requires a selective degree or an art historical background to appreciate it has a limited but devoted audience, so we can be happy for that art and its connoisseurs without feeling any sort of insecurity or conflict about our own taste.

I have a good friend whose mother desperately wanted her to marry someone rich and ideally a doctor and went to great lengths to make introductions over multiple decades. This kind of pedigree sounds great, but love doesn’t work this way. We cannot force ourselves to fall in love with people because of their resumes and a sense that we “should” love them—and those who do have miserable marriages. The same is true for art. We love who and what we love for a variety of reasons. This doesn’t mean we cannot educate ourselves and expand our tastes and learn to love new things; it doesn’t mean we cannot conduct diligent research to understand more fully why we love the art (and humans) that we love. But love, at its deepest and most effective, is instinctual, nonverbal, and complex.

I was trained as a painter and, whether painting is currently considered alive, dead, or the walking un-dead, I’m always going to adore a luscious painted surface, the drips and dribbles of a fluid medium, and the layered palimpsest of color glazed under slick layers of pigment. It fills me with a wicked kind of joy, being around large and viscous surfaces that surprise me in their decadent liquidity and nimble brushwork up close, from Tintoretto’s fat-bottomed cherubs to John Singleton Copley’s lace to Kerry James Marshall’s classical compositions to Joan Mitchell’s luminous, feathery fields of brushstrokes. Like certain humans I choose to spend time with, certain works of art inspire, challenge and energize me; I can learn from them directly by just standing in front of them and allowing myself to feel and think and marvel and ingest.

We live in a decadently rich time in history with a vast array of technological resources at our fingertips, but many of us are not living deep and rich lives. We’re too busy, too distracted, too challenged, too focused on making money and winning, too obsessed with our smart phones and devices, and we’re so insulated from discomfort we avoid mysterious new experiences and people, especially those which might initially seem like a waste of time or beyond our limited expectations. Human beings are so hungry for meaningful interactions, and we’re missing out on some of the best aspects of being alive, as individuals and communities.

Great art—the art that speaks directly to us as individual humans—takes us far beyond our daily lives into a place where learning, connection, mystery, and wonder can offer us deeper and better relationships with ourselves and the world we live in.

Featured Image: Tracy Emin, “You Made Me Love You,” 2010