Sun streams in through the large windows at the Walters’ 1 West Mount Vernon Place as Antonio McAfee shows me his installation “Unmaking and Making.” Shadowy faces from long ago, printed on acrylic and held together by glassy string, revolve slowly in a solemn dance, catching odd bits and speckles of afternoon light. Through this unsmiling and prolonged pirouette I can see the Washington Monument outside the window. It feels like a gentle but unmistakable lesson about the relationship between space, time, people, and power.

McAfee’s work has for years been centered around using photographs from W.E.B. DuBois’ Exhibit of American Negroes (1900) originally made for the Paris World Expo and now housed in the archives of the Library of Congress. His current work shares space with more contemporary images of Black life to create composite, otherworldly pieces that feel simultaneously silent and orchestral.

In other pieces, like “The Ruler,” the artist meshes contemporary influences such as family members who have passed away and cultural icons like D’Angelo, Sly Stone, and Bette Davis with images from the DuBois archive to create a larger narrative about the resilience and creativity inherent to Black history and culture. “It’s important to me to feel like I have the authority and confidence to add to” the archive, McAfee says. “I’m branching off into turning that into work that has inspired me and helped me think differently about myself and the culture I’m in.”

He sees this re-negotiation of history as a complicated trajectory, and acknowledges that picking out images from a pre-existing set can be scatterbrained at first. However, being an inquisitive person by nature has its advantages. “I’m very focused on American history and its reconstruction, but within that I want to connect disparate things together,” he says. “It is a disservice to just leave it in the past. I want to deal with it as if the purpose of it is that future people, generations, and demographics see that they have ownership and authorship of it as well. And so, to add on to that work is the point—to continue their life.”

There are 363 studio portraits in the Exhibit of American Negroes, and McAfee’s projects have used every one of them at one point or another. Curating images from within the archive depends on what each project invites him to look for. For one project, he focused on people’s attire: “the blouses, the ruffles, the embellishments, the hairstyles.” For another, he looked at poses: “the most statuesque ones.”

Among the many approaches to taking old photographs and rethinking them, McAfee’s method feels almost sculptural—creating distinct structures that take up space in ways that photography often doesn’t. It also makes his decision to incorporate the DuBois portraits, which were originally exhibited to combat race biologists and showcase the economic, social, and cultural contributions of African Americans, all the more deliberate. Viewed within the polished and ornamented interiors of the Walters, these faces are emblematic of an effort to turn a deeply flawed and unspeakably cruel effort at scientific enquiry on its head with empirical evidence. The gestures, gazes, and poses may seem uncomplicated, but they bring to the fore a nuanced leitmotif that is at once both a defiance and a critique of privilege.

The portraits for DuBois’ 1900 exhibition were initially created to assert dignity in the face of popular caricature: scientific opinion at the time was fond of painting white as advanced, black as primitive. A whole century later, the discipline of photography is still capable of manipulating opinion and influencing perception—think of all the different ways in which Black faces and Black bodies are criminalized and/or exoticized in popular media today. “There’s something about being closely tied to the historical image, the referent, and to have that be apparent,” McAfee says, “but also to not be stuck in there, to be able to take that to another place.” Through his installations, traversing experiences drawn from an unjust past to an unfair present seems only natural: Their majestic expressions continue to argue wordlessly for the need to reclaim and repair.

Photo by Ana Tantaros, Side A Photography and Cara Ober

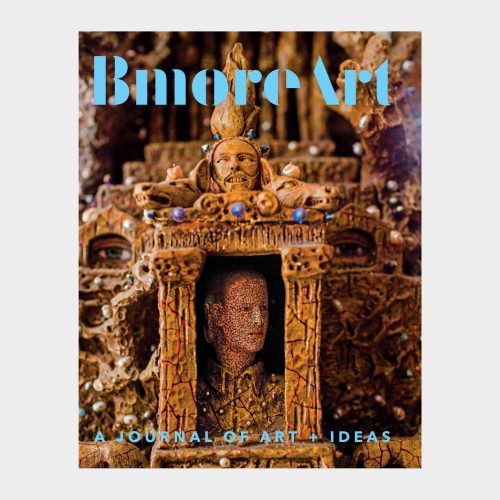

This story appears in BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas Issue 08: Archive.