Adrift in the Bulgarian capital of Sofia, the American narrator of Garth Greenwell’s debut, What Belongs to You, falls hard for the young hustler who solicits him in the restroom of the National Palace of Culture. The novel, a crucible of illicit desire and familial trauma, came out in 2016 to a mainstream audience that was still lukewarm to queer stories, let alone queer sexuality. Mere months had passed since marriage equality won the day in the United States. Aspects of gay culture like cruising or drag were burgeoning novelties if not still outright taboos. And there was much ado about Greenwell’s lush portraits of gay sex, especially in the context of a relationship that was turbulent and transactional from the start.

In fact, Greenwell wanted to push the sex further in his debut. “Literature is the most powerful means we have for communicating consciousness,” he writes in an essay for The Guardian. Literature can “reclaim the sexual body as a site of consciousness” in the era of self-commodification. Now that queerness has become the lifeblood of culture, it’s tempting to characterize queer art as a victory, the fulfillment of a social justice manifesto. But queer art, like art in general, is only the inciting incident. It’s the breeding ground for new possibilities, or the excavation site for ancient truths about human nature.

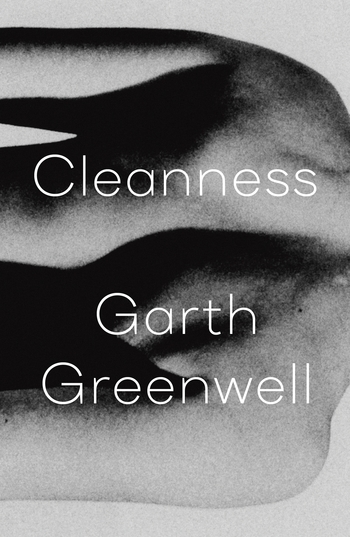

Enter Greenwell’s grueling but ultimately exhilarating follow-up novel, Cleanness, which was released earlier this year. We return to Sofia, a city haunted by its bloody Ottoman past and all but abandoned by the globalized West. Our unnamed expat continues to spend his days teaching O’Hara and Whitman at the elite American College, and his nights cruising online forums and public bathrooms for the company of other men. Bulgarian austerity fills the negative space, stifling affection and sequestering emotional upheavals behind closed doors. Cleanness unfolds in a gorgeous triptych further refracted into trios of interconnected stories (nine in all), forming a constellation of moments in the narrator’s waning time in his adoptive country. Each vignette is a high-wire act, teetering along the razor’s edge separating shame and desire, passion and violence, actualization and obliteration.