Early this December, when my kids asked me what I wanted for Christmas, I didn’t skip a beat. “Just one singular thing,” I told them. “Breakfast with Jesmyn Ward.” Her new author photo had caught my eye on a poster at the Enoch Pratt Central Library: she was going to be featured at their next annual Booklovers’ Breakfast in February.

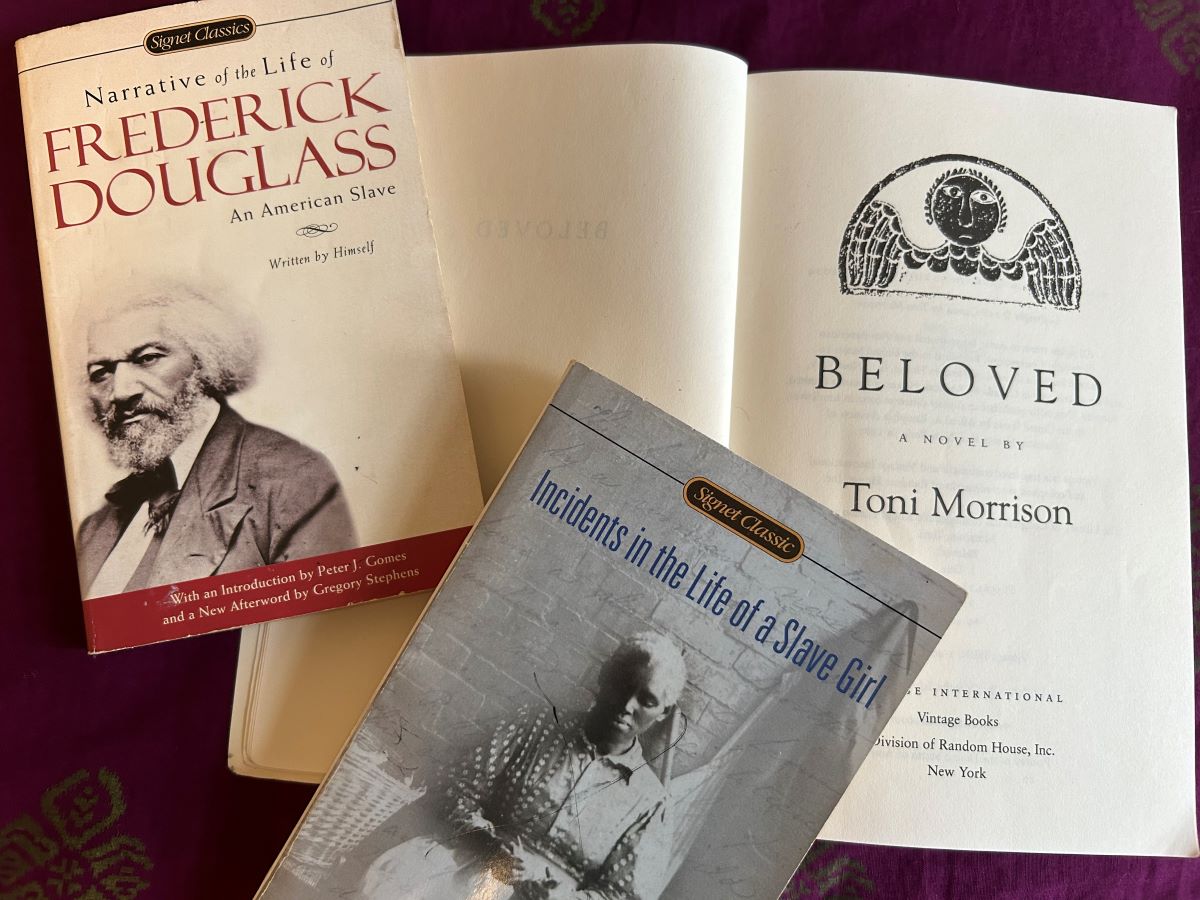

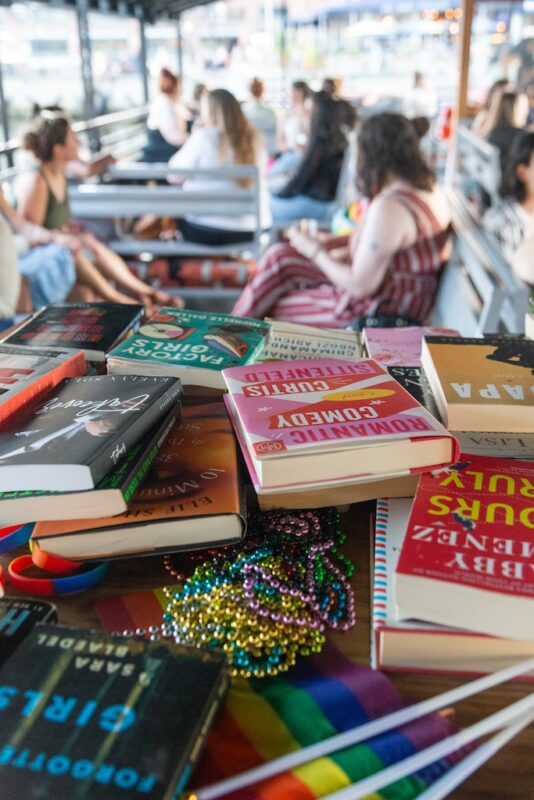

Offering my kids a visual aid, I laid before them my cherished, marked-up copies of Salvage the Bones and Sing Unburied Sing, which surely they must have noticed me rereading year after year as I teach them at University of Baltimore. “Jesmyn Ward,” I repeated. “Got it, girls?” They are eight and eleven years old—the tickets for the Booklovers’ Breakfast were well out of their price range at $50 a seat—so this all relied on them getting the message to my wife, to whom, taking a leap of holiday faith, I didn’t say a word.

Bless them all. On Christmas day, I opened an envelope to find one of my wife’s signature hand drawn coupons. I had a ticket!

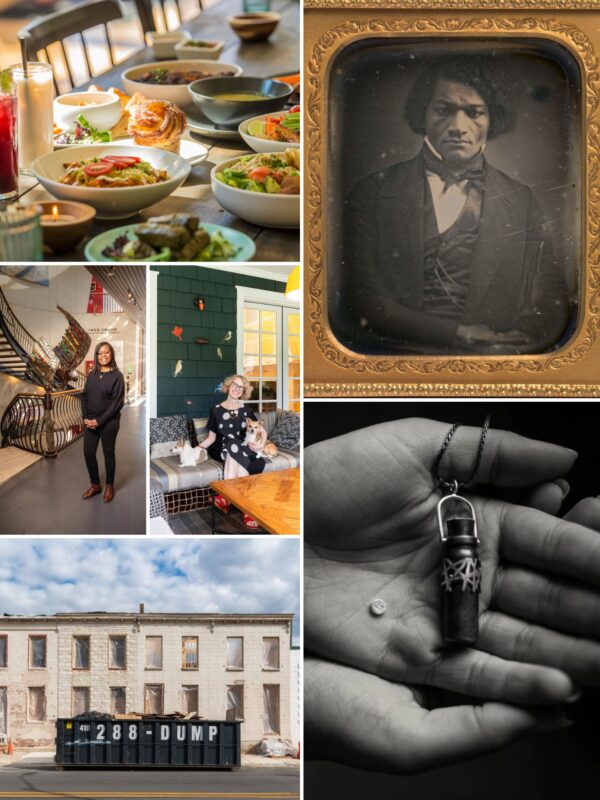

The Booklovers’ Breakfast is the Enoch Pratt Library’s annual kick off to Black History Month. In years past, it has featured prominent Black writers and thought leaders like April Ryan, Walter Mosley, late congressman John Lewis, and many more. But this, the Pratt’s 36th Breakfast, was to be my first. And so, with little idea of what to expect, I daydreamed about Jesmyn and me sitting across a fancy table, spearing pancakes and passing the bacon whilst talking about characters we had yet to bring to life.

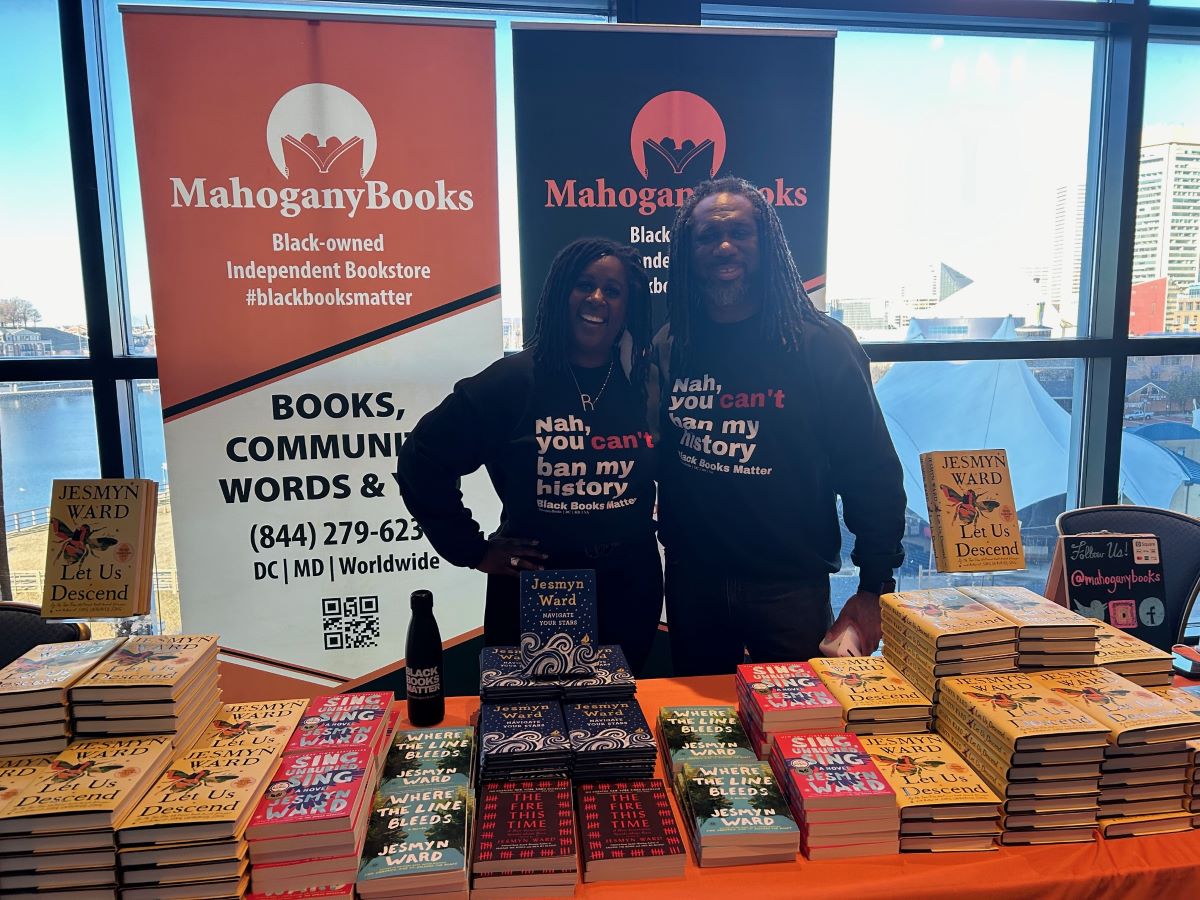

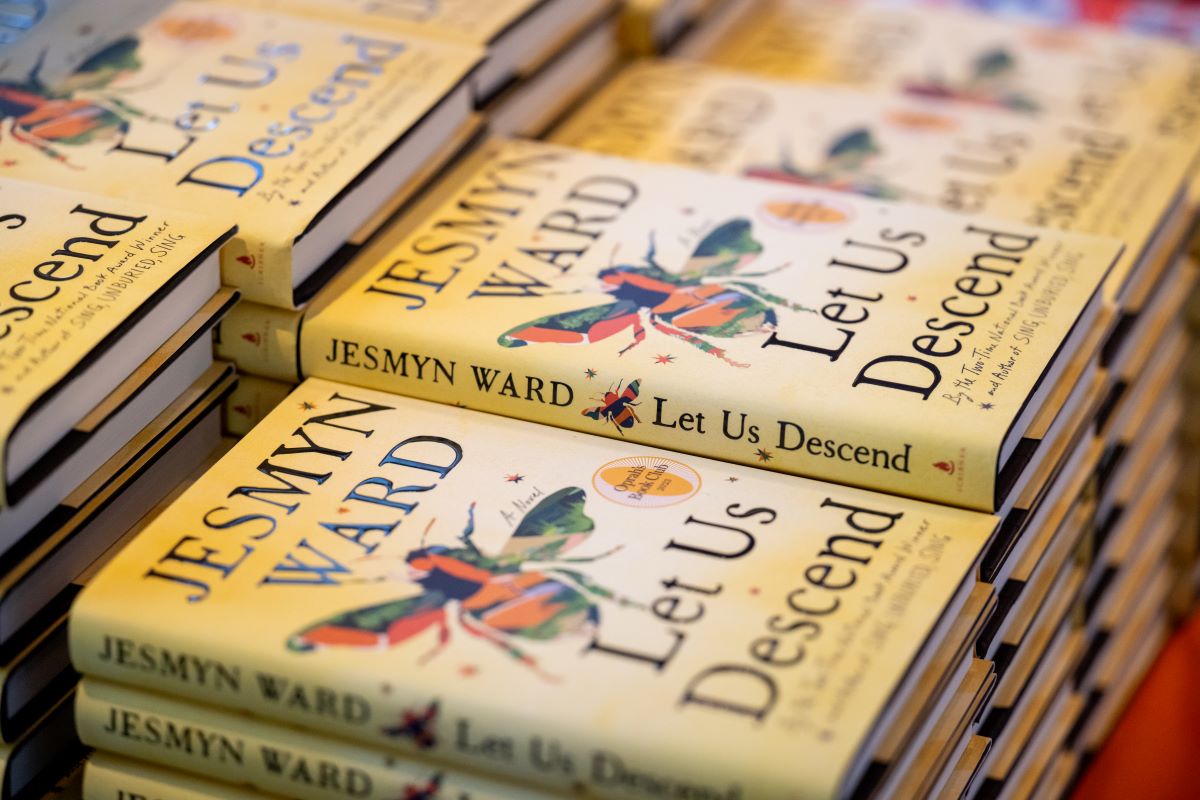

Fast forward to reality: February 3, at 8:26 am, I scored one of the last spots in a quickly maxed out parking garage, then was swept in a swell of Black women following our reservation directions to the entrance of the Baltimore Marriott Waterfront Hotel. Guided seamlessly by Pratt employees and volunteers, we flooded the ornate hallways and staircases, the whirls of your sister’s/ auntie’s/ mama’s/ grandma’s perfumes announcing to all ahead and behind us this was an occasion not to be understated. We would add up to roughly 740 attendees, gathered at last in the hotel’s sprawling Harborside Ballroom.