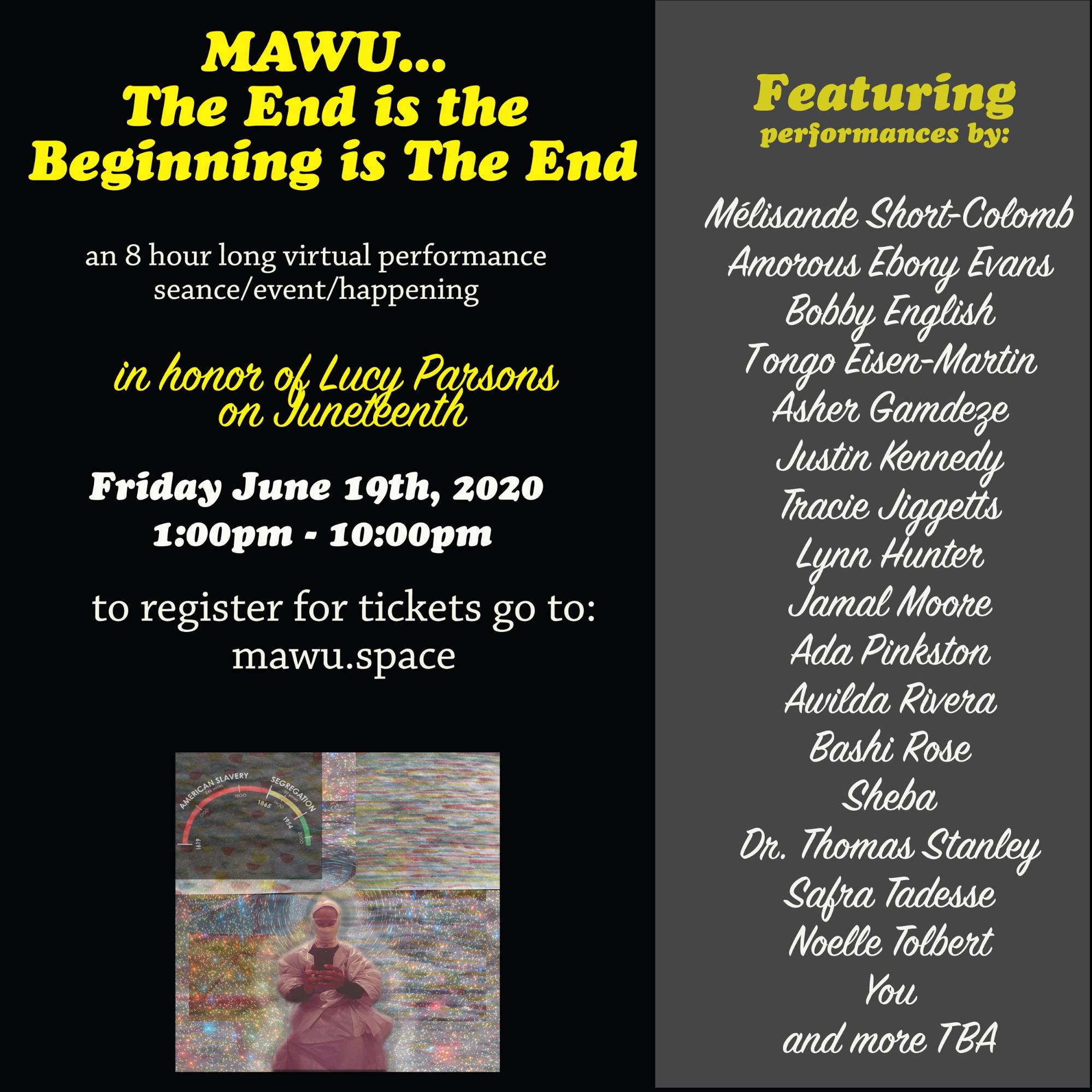

“I thought a lot about how I would curate performances and experiences for a virtual audience,” Pinkston said. “Curating and organizing is part of my praxis because I am also an educator. As someone who works in the social sphere, I think that performance is another way to consider the relationship that the art object has to both public and private spaces because performance art is something that cannot really be commodified (with a few exceptions like Marina Abramovic or Tino Sehgal). In terms of concept, I am always thinking of ways to engage audiences with material that is not part of the dominant narrative found in McGraw Hill Textbooks.”

A poem by Audre Lorde (Pinkston’s favorite poet), “MAWU” inspired the title of this Juneteenth performance. In African religious mythology, “Mawu” refers to a female creator deity, but can also be translated to mean “God.” Lorde’s poem is an ode of grief to her dying mother.

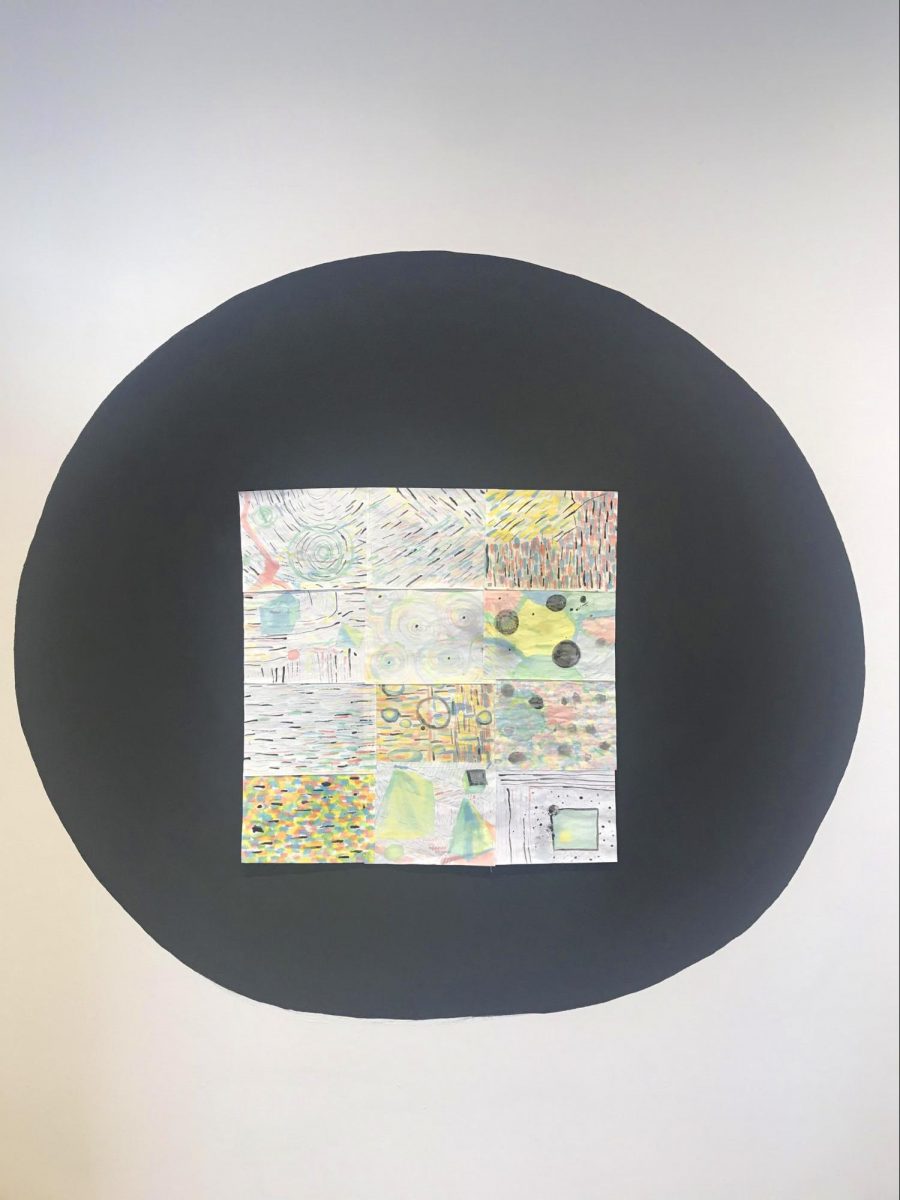

Pinkston said that, for her, MAWU is about using “performance as ritual and ritual as performance,” and that the eight-hour-long piece “will test the limitations of what it means to be a spectator, a creator, a passive consumer, and the limitations of language on universal experiences.” The durational performance and installation present new opportunities to learn how to confront these parts of ourselves and our histories. For Pinkston, the eight hours of endurance, which symbolizes the eight-hour work week that Parsons fought for, also echoes the freedom that was first denied and then obtained by Black people in Texas on Juneteenth, offering a powerful exercise in self-liberation through art, collaboration, and community.

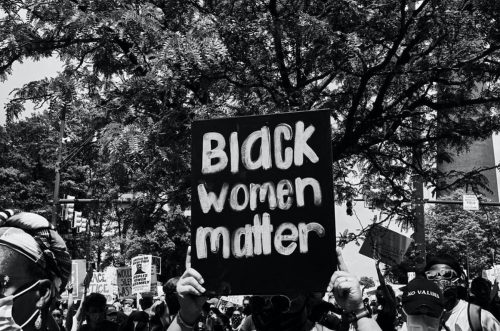

When we discussed the seemingly new, widespread attention now given to Juneteenth as a day of celebration around Black liberation, Pinkston said, “We are in a really interesting moment. People are talking about things in a way that they never have before, I think that’s why people are recognizing Juneteenth. Right now there is a recalculation. Things are moving. Performative gestures have always been performative, but now it is just more apparent because so many corporations reach out and say things. People recognize the performativity of ‘solidarity’ and they’re trying to back up their actions.”

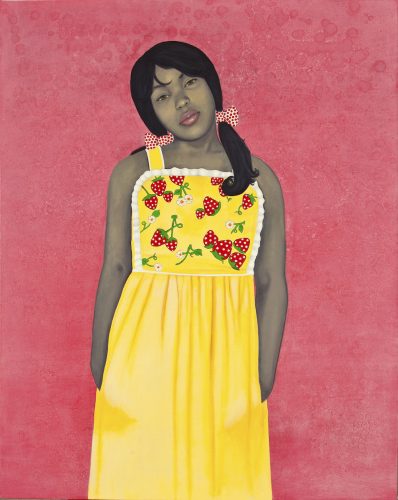

However, the idea of subjectivity and performative gesture is highly relevant for an artist, performer, and curator like Pinkston. “The performativity of race is always present, whether people are conscious of it or not,” she said, adding that it’s important that her artwork challenges boundaries and expectations for herself, her collaborators, and her audience, building relationships between disparate subject matter to present a multi-faceted whole.