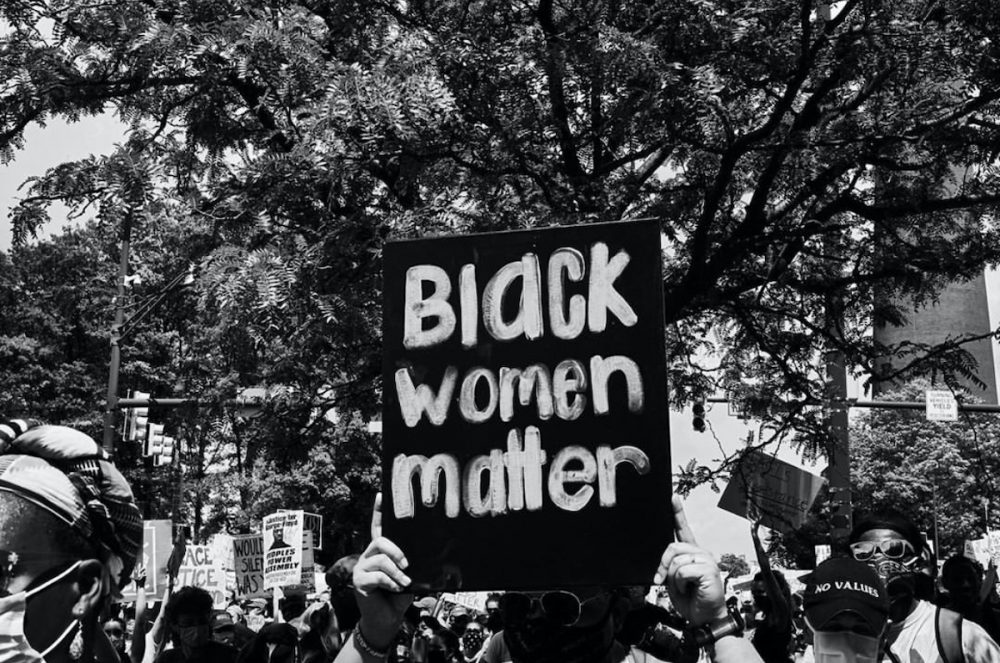

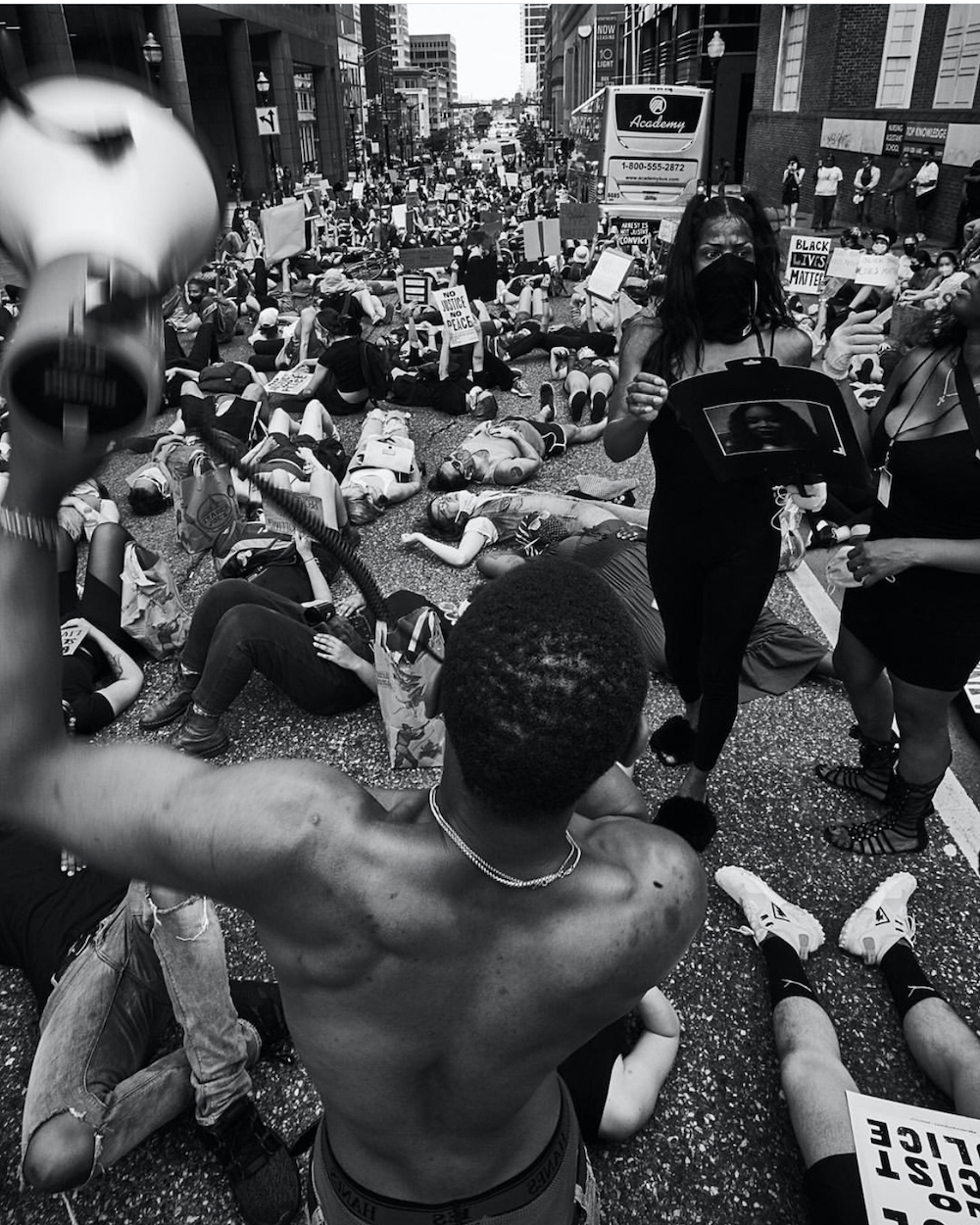

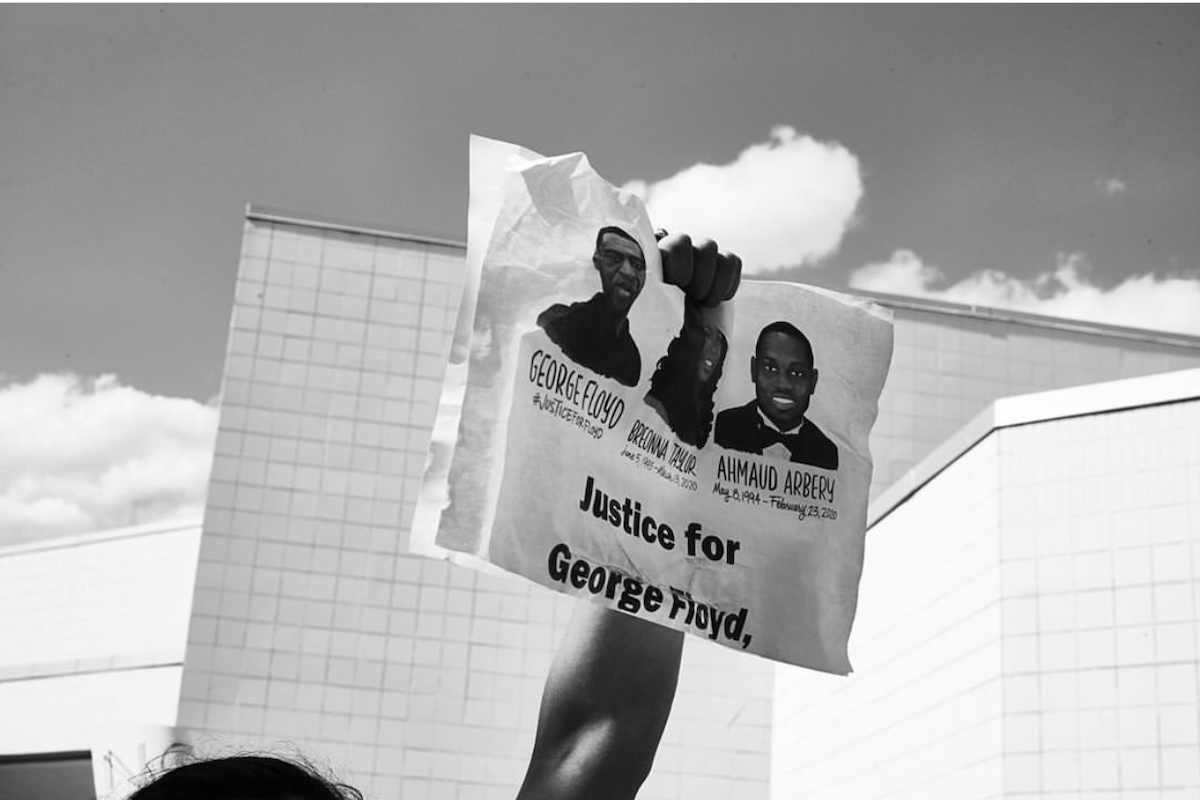

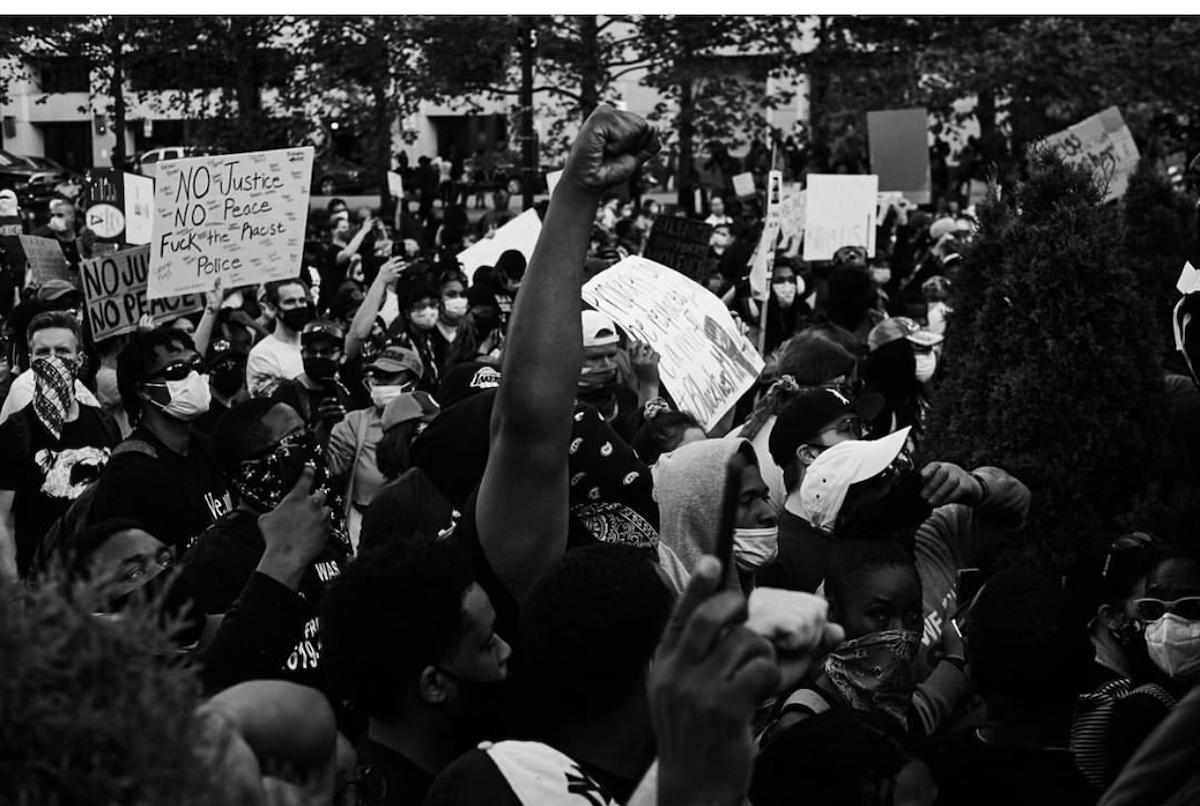

The police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis last month sparked hundreds of thousands of people across the country to protest, participating in marches, vigils, and mass demonstrations against systemic racism and police brutality. Mainstream media covered these protests extensively at first, some especially focused on the destruction of property more than the conditions that provoked such a response. Several weeks later, as largely nonviolent protests have continued across the country, including Baltimore, that coverage has waned.

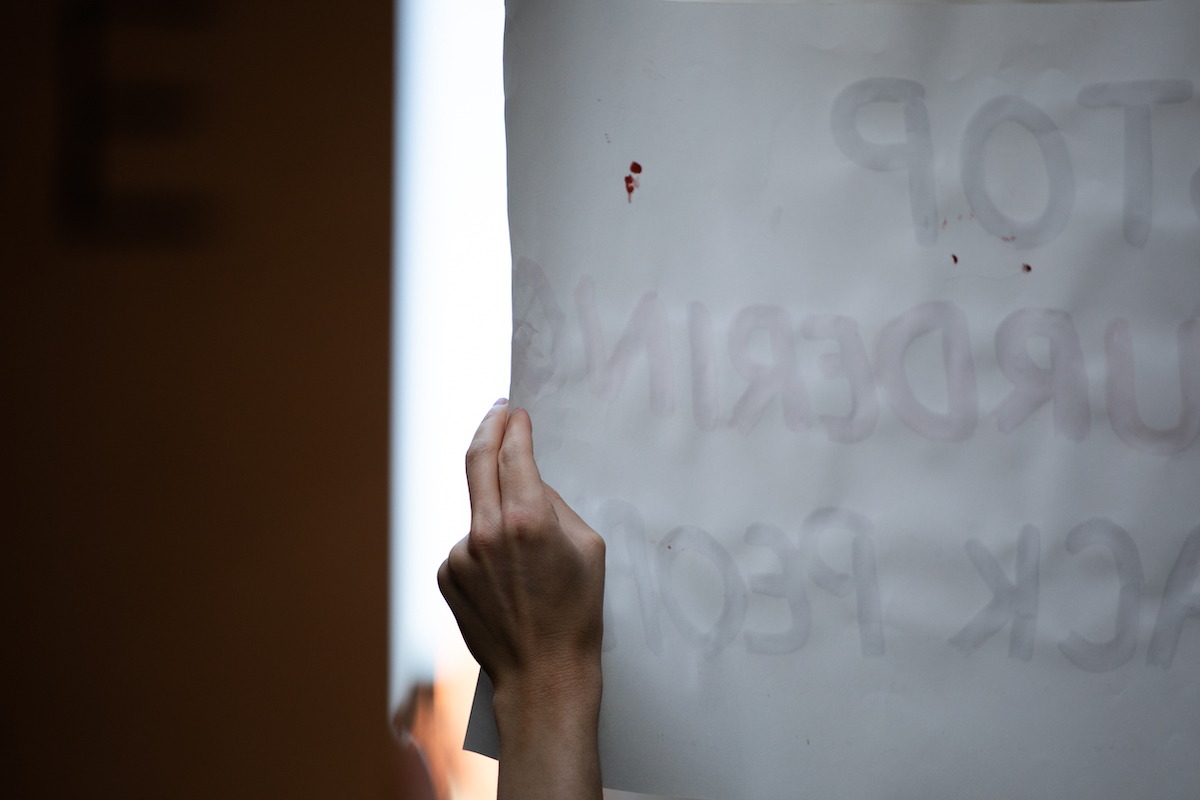

We’ve seen this before, like in Baltimore five years ago when the media helicoptered in to tell an incomplete story about the uprising sparked by Freddie Gray’s murder and then left once the fire died down. So it is essential that photographers, writers, artists, educators, and activists record and take note of what goes on, and that they continue to use a variety of tactics to make demands of elected officials. It’s crucial that those present at protests are able to tell their personal stories and record their experiences, especially those historically excluded from the narrative.

Online platforms like Instagram and Twitter have made images of protests available to a much larger audience than ever before and, in the case of Devin Allen in particular, have opened up professional opportunities and fame. Five years after his iconic image from a 2015 Baltimore protest for Freddie Gray made the cover of Time magazine, Allen’s photograph from a recent Black Trans Lives Matter protest and vigil in Baltimore (which appears below) was recently selected for Time’s cover.

The ethics of photography are always up for analysis, and within the context of protest right now those questions are particularly important. As suggested by Authority Collective, a group of women, nonbinary and people of color working in the photo, film and VR/AR industries, photographic documentation at such protests can yield unintended psychological consequences: “The constant circulation of images depicting violence on Black bodies adds to the desensitization toward Black suffering, while white bodies are photographed with dignity, subtlety and nuance.” There are also discussions about potential harm and repercussions for protesters identifiable in such photos as well as an insistence that Black Lives Matter protests, in particular, should be documented by the Black artists whose lives have been most directly affected by systemic racism and police brutality in America.

BmoreArt talked to six different photographers, five based in Baltimore and one in DC, about what it’s been like to participate in and document the recent protests.