The phrase “I’m not an expert, but I watch a lot of YouTube” has taken on new meaning over the last few months, when face-to-face access to the professional hairdresser, chef, or fitness expert feels like a distant memory. As an adjunct professor, I’ve been spending parts of these summer days teaching on Zoom and figuring out how to do it better for whichever of the proposed fall 2020 hybrid learning models the college and university where I teach settle on, come August.

As academics prepare to be at least partly communicating and working with students remotely this fall, now is the time to challenge ourselves to embrace technology we may have been ignoring. What this time affords educators that the slapdash spring conversion to online teaching did not is the opportunity to plan. And teachers love planning. For many of us, it’s why we get up in the morning—every day is a fresh opportunity to break down information into manageable chunks for other people.

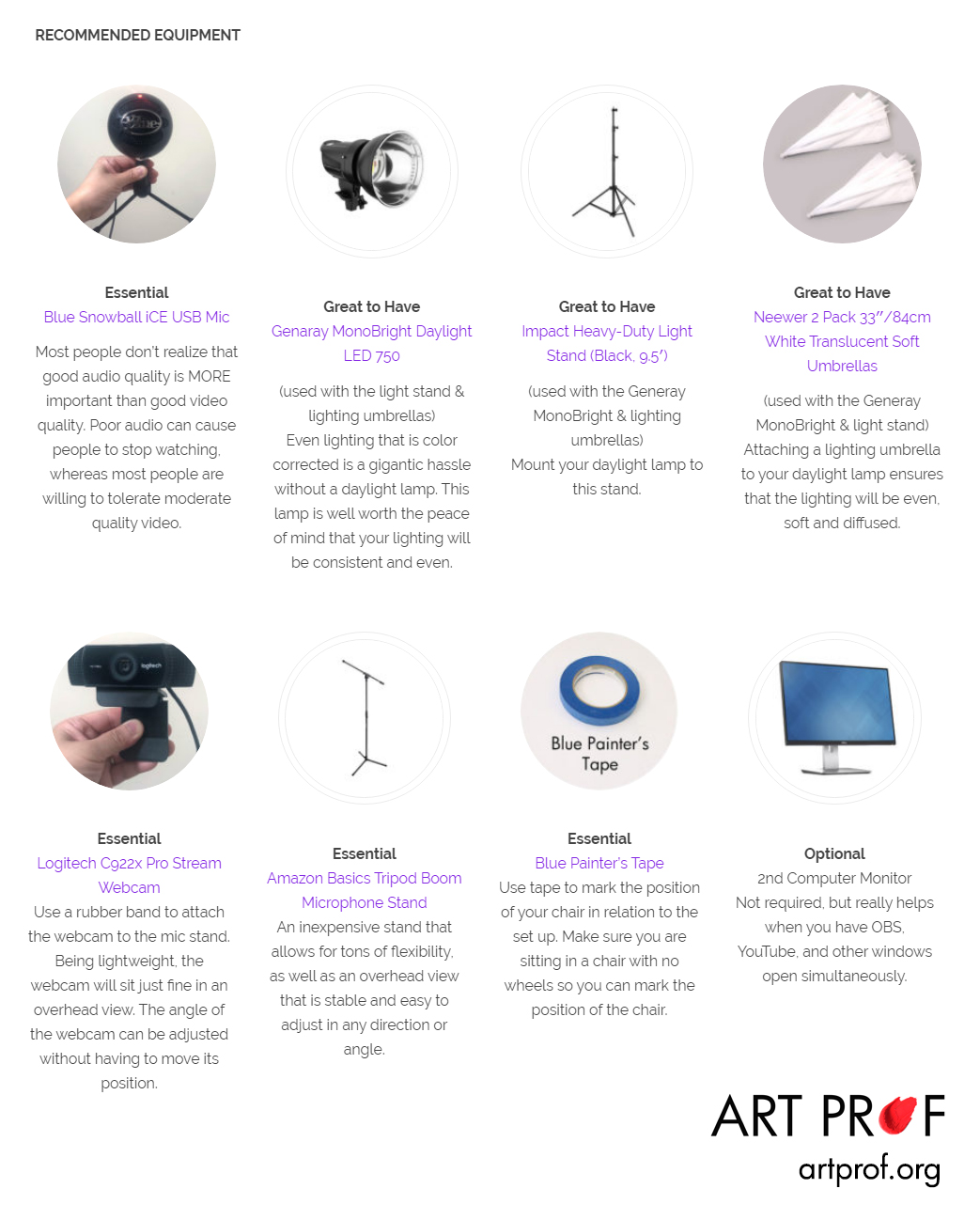

Since March, many resources have emerged for educators, so this is not an overview of how to holistically convert your in-person class to draconian folders on your institution’s poorly designed remote-learning platform. For that, I point you towards the internet where good folks have shared nuanced knowledge on how to win your battles with Canvas, Blackboard, Flipgrid, Padlet, and others. There are also many great tutorials for setting up a critique online, instructing students how to photograph their work with only a smartphone, and various classic drawing lessons.

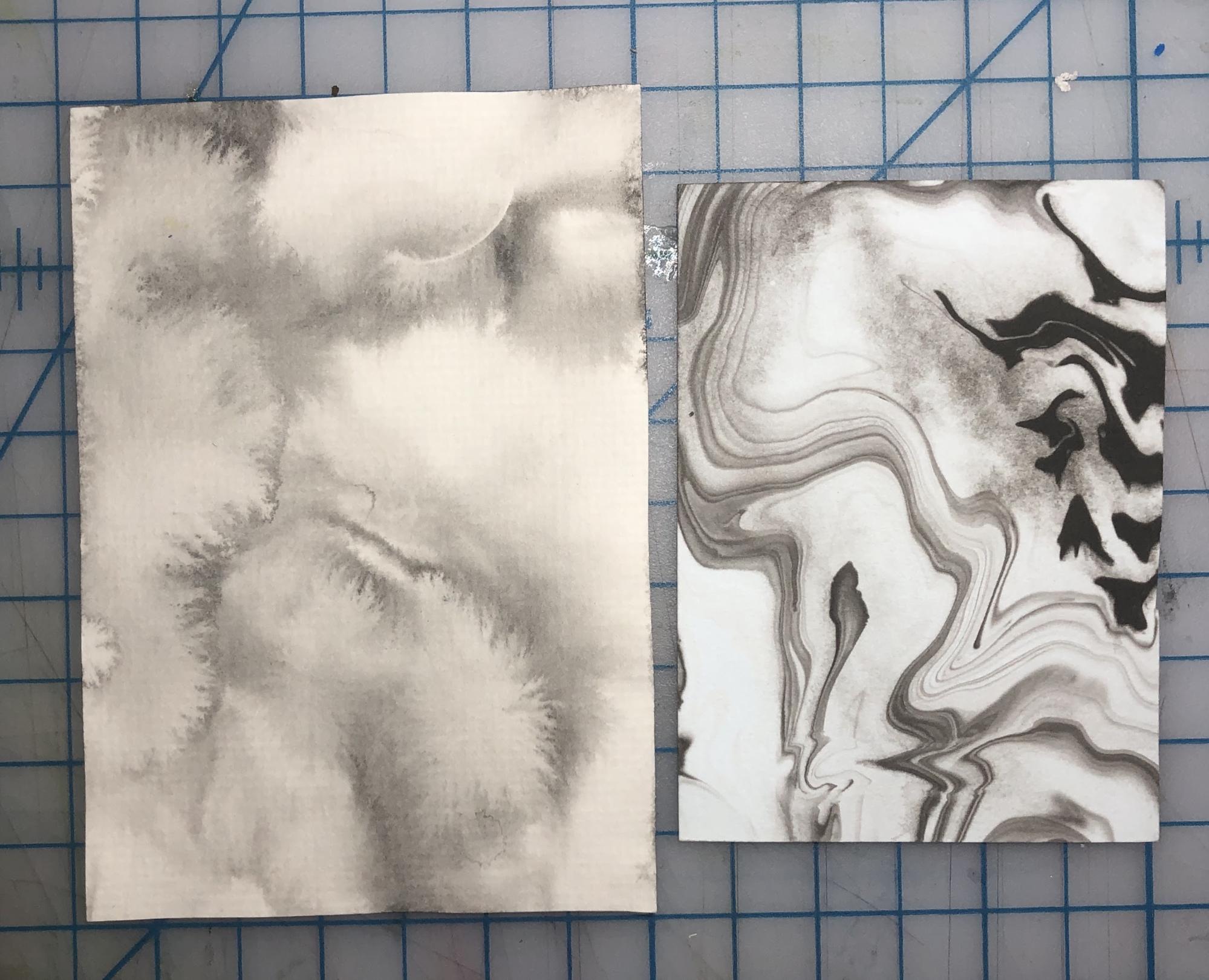

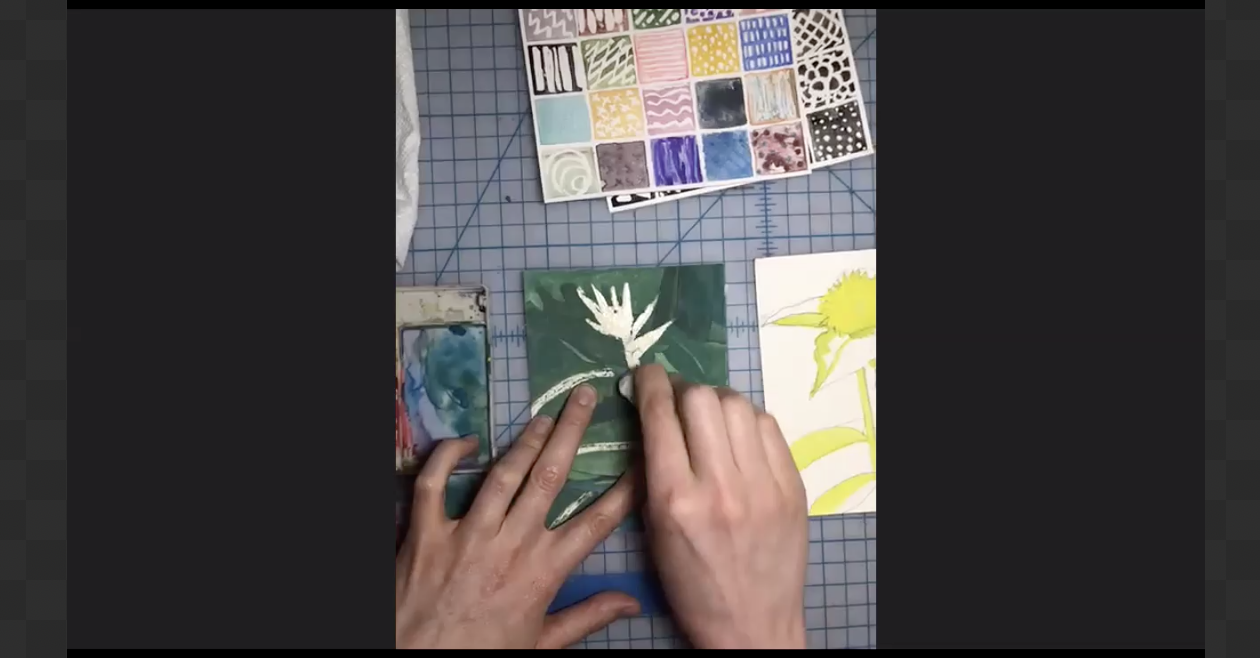

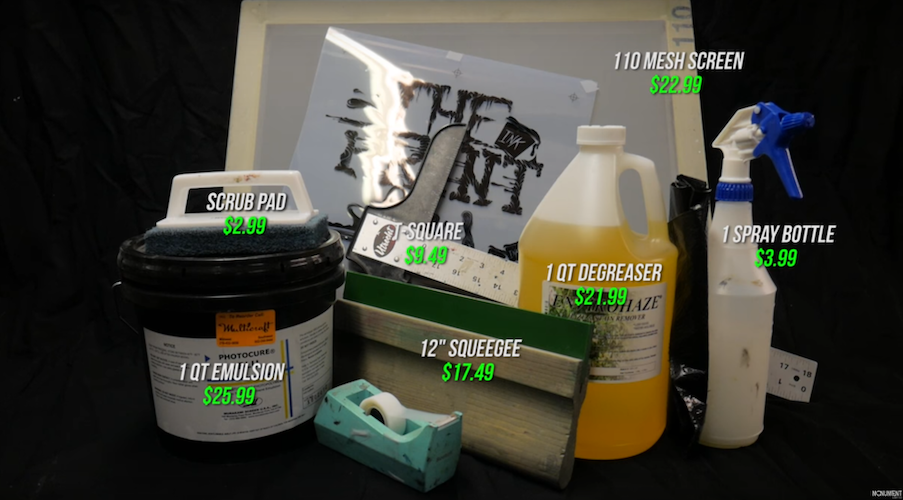

I decided to focus instead on a cornerstone of visual art instruction that has emerged newly important during the age of corona: demonstrations. Depending on the grade level or subject you teach, demos may be your bread and butter, or you may only do a few in a typical school year. But this is not a typical school year, and demonstrations serve a dual purpose of humanizing you to your class so you’re not just a robot-taskmaster emailing them about deadlines, as well as showing and not just telling how something can be done. This method of instruction is more equitable for students with learning differences and, frankly, it’s popular with a generation that has grown up watching screens. Demos are personal moments where instructors really share their knowledge, put their spin on a subject, and address common mistakes with advice for how to avoid them. When done well, they are the very best parts of education.