I write non-linearly. I take notes on various pieces of paper, on my phone, and on my desktop, and they are in no particular order. Most of my writing evolves from a stream of consciousness: flurries of typing coupled with notes covered in the chicken-scratch yet Unabomber-esque style of text known as my handwriting. My writing style often frustrates me—it’s anxiety-inducing to be so disorganized, and I sometimes can’t read my own handwriting. But while reading Black Futures and writing this review, I believe my methods helped me. In the editors’ letter, writer and curator Kimberly Drew and New York Times Magazine staff writer Jenna Wortham suggest that Black Futures is not necessarily meant to be read in chronological order. I read and wrote in response to what resonated at various times, in various places, at various paces.

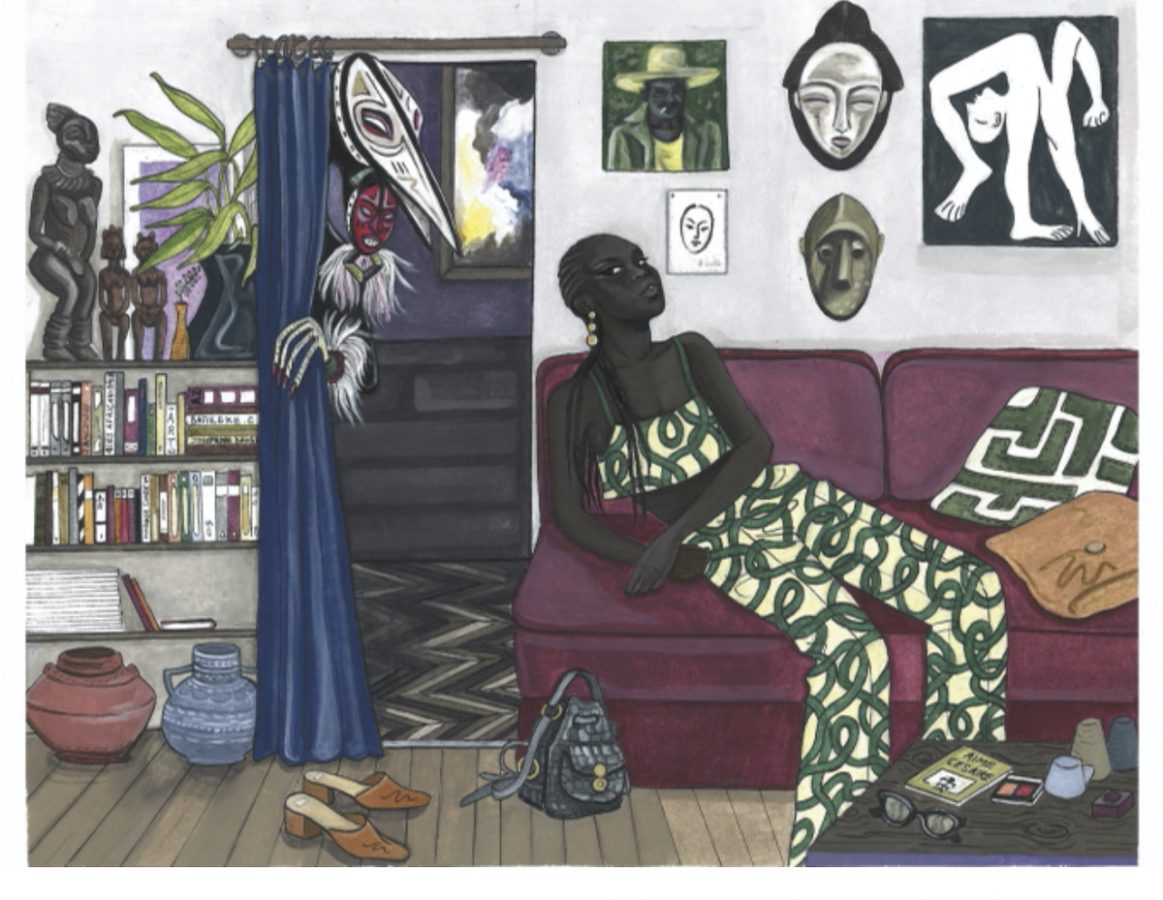

The origin story of Black Futures begins with a Twitter DM between Drew and Wortham in 2015. How fitting that such a mundane moment would birth an entire literary universe. Wortham and Drew took more than a hundred submissions by journalists, artists, critics, essayists, organizers, and more, and elegantly transformed them into a collage of the Black radical imaginary. It is a flurry of Black joy, Black expression, and Black connection.

I found Black Futures’ intentionality delicious. Tiny textual moments in the bottom-left corners of numerous pages gently suggest related entries throughout the book, adding to its non-temporal, non-traditional format and nature, and emphasizing the editors’ wishes that you read at your own pace and in your own way, and get through it how you want to get through it. Any path will be an exercise of interstellar and intertemporal travel through a Black-ass book.