Andria Nacina Cole’s journey to situate herself in her authentic power can be traced back to the late ‘90s on a bench at Morgan State University. It was her junior year, and she had not yet declared a major. At the time, she was writing what she describes as “morbid poems that were extra violent and over the top, and I’m just like ‘Ooh, I’m talented.’ Thinking I’m getting down when really I didn’t know what the hell I was doing.”

Wanting more direction and commitment, Cole realized she needed to declare creative writing as her major. Without hesitation, her mother told her, “Go ‘head. Go for it. Do it.” Twenty years later, now an educator and a writer (and a mother herself), it’s no wonder Cole calls her students “daughters” and builds them up with the same kind of fearless encouragement.

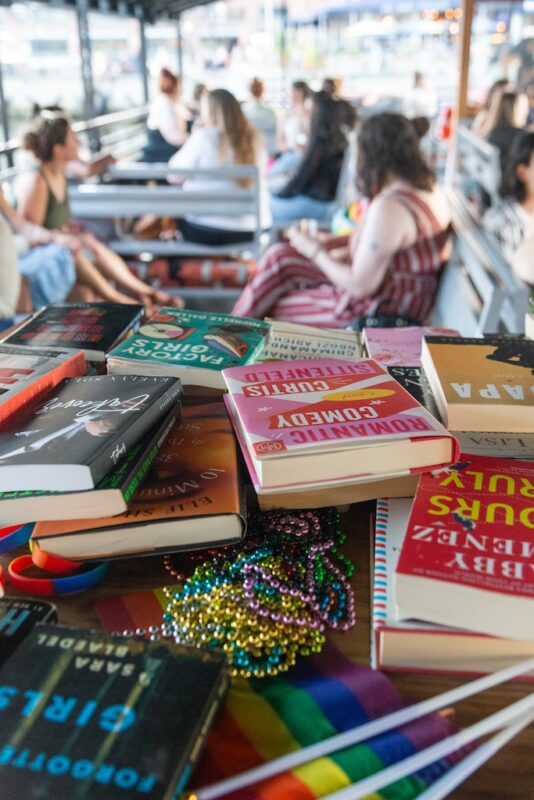

The author of the novella Men Be Either Or, But Never Enough and the poetry book Anthem: For Colored Women Only, Cole uses the same writing ethic as her living ethic: to speak truth. One way she does so is by writing in the same dialect that she speaks in, inspired by Black women who write with Black women as their audience, like Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow is Enuf, a monumental choreopoem written completely in African-American Vernacular English (AAVE).

“Ntozake Shange has a philosophy and determination to give Black women and girls the language for their experiences ‘cuz she knew it was either gonna inspire or it was gonna stunt,” Cole says. “And right now, if we’re using their [the oppressor’s] language, it’s just going to stunt us because violence comes on down into the words too.” She points to the fact that enslaved people were not allowed to learn to read because “that was where freedom was.” Cole’s belief in language as freedom is the catalyst for her life’s work—to motivate Black girls and women to use language as a tool for finding their own authentic power.