Seemingly overnight, the need for artists breaking all kinds of taboos on museum walls has become acute, and my original desire for more nuance and evolution in this work has been superseded by the need for blatant resistance to the religious right, right-wing politics, and all those who fund them, especially those sitting on museum boards. The reminder that bodily agency for women is precarious means that we need art that offends and challenges the movement conservatives who desire to take personhood away from all historically marginalized populations. With the passage of SB8, and the restrictive future it portends, the artistic freedom to thumb your nose at the misogynistic haters and naysayers is everything, now and again and perhaps forever.

At the BMA, a sign was posted at the entrance of the contemporary gallery where Wilderness hung that read: “THIS GALLERY CONTAINS MATURE CONTENT.” After my last visit over the summer, I texted the artist a photo of the sign and we had a laugh about the prudishness assigned to nude paintings of women by a woman. She pointed out that the museum has plenty of paintings of nude women by men in other galleries, but none bearing a warning sign. At the time I found this humorous, but now it’s sobering. Why is a painting of a nude woman by a woman offensive, but not one by a man? I realized I had become complacent, conditioned to see the world in a way that was actually not in line with reality.

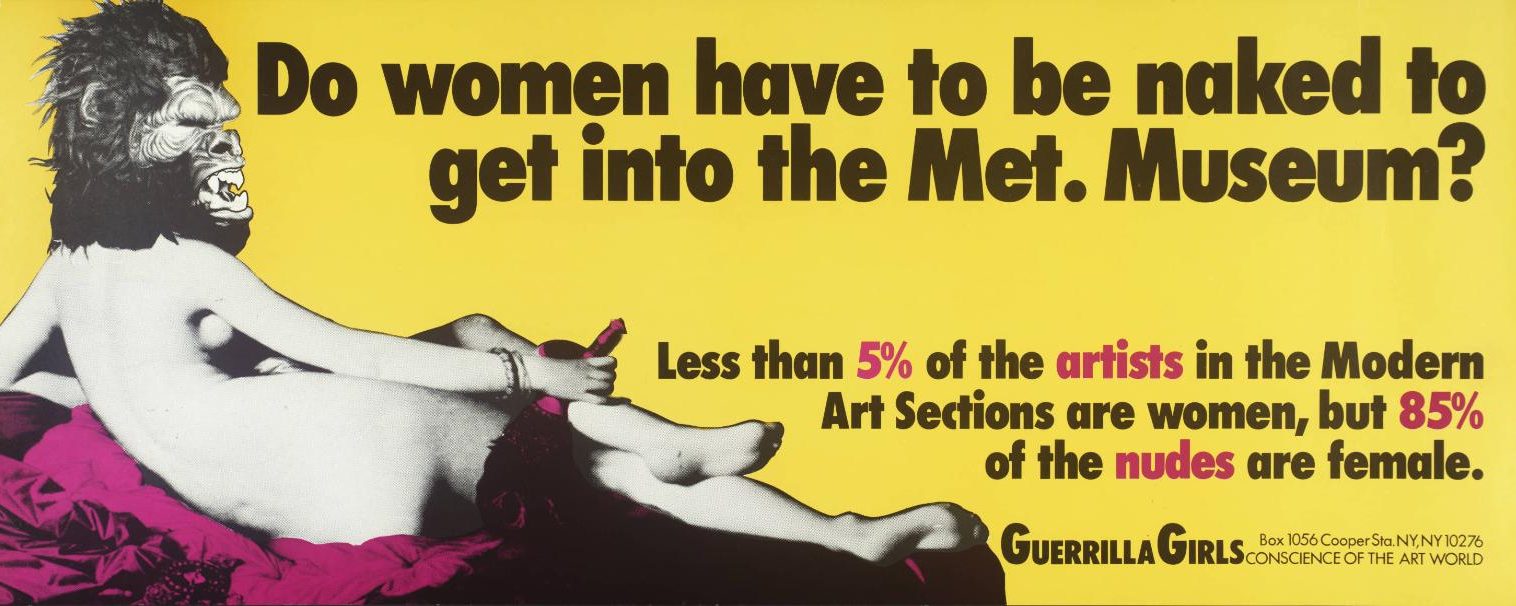

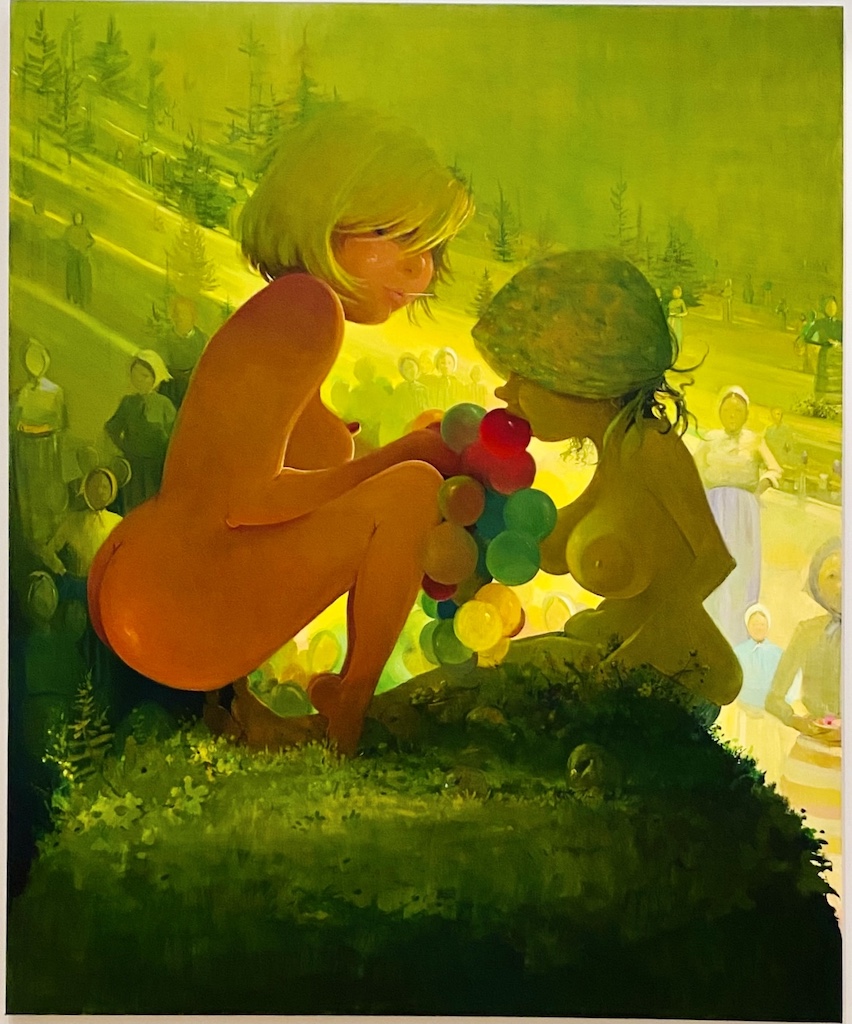

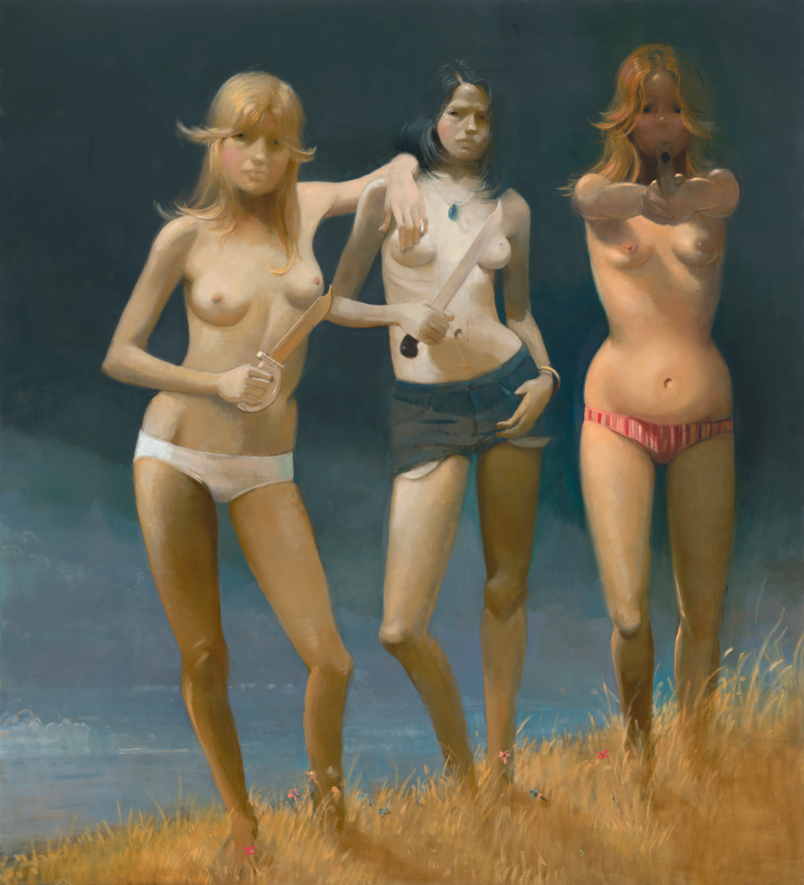

In the mid-1990s, Yuskavage grabbed national attention by painting sexually liberated nude women inspired by pornography. Unapologetic, crass, and sexy, these pictures challenge the limits of feminism, pushing back against its sometimes puritanical attitudes. More importantly, her paintings question the toxic impact of the male gaze, clarify the hidden relationship between art and pornography, illuminate the influence of sex workers throughout the history of art, and confirm the sexual freedom of women. Yuskavage’s “translation” of an art historical canon chock full of nude women painted by male artists gives us an opportunity to reframe our understanding of what and who these kinds of images are for, to understand the patriarchal power structure that continues to objectify, shame, and erode the bodily agency of women.

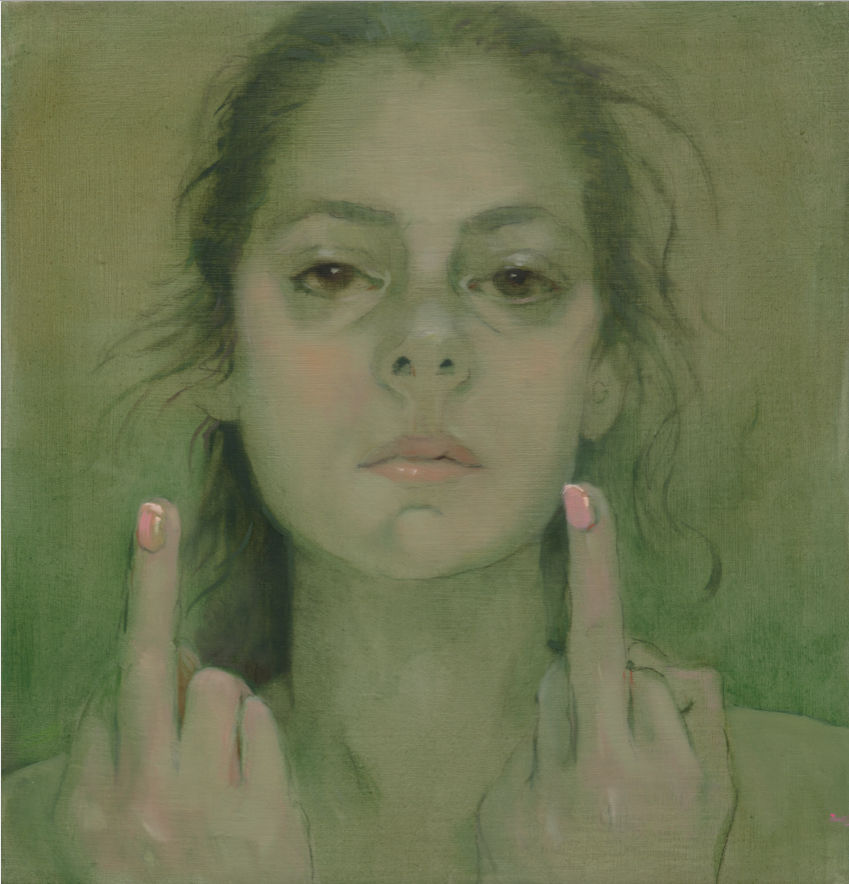

After thirty years of making deliberately provocative paintings, Yuskavage, along with many other women artists and activists, has managed to create a more inclusive and accepting space for women—as artists, as sexual beings, as muses, as individuals. Regardless of what’s happening in the world, her primary focus remains on her personal desire to make these kinds of paintings over and over again, and maintaining the freedom to do so. In addition to the BMA exhibit, Yuskavage opened New Paintings at Zwirner on September 9, 2021, where two bodies of work function in tandem: one which explicitly considers the intimate and predatory relationship between artist and model inside the studio and another where she reimagines her earlier “Bad Babies” series, depicting young women in adversarial poses, holding toy weapons and flipping the bird.

“She made pictures about women looking at themselves, of women looking at other women,” writes Molesworth in the Wilderness catalogue. “And all these images had the DNA of six centuries’ worth of paintings made by men for men of means that were about looking at women, that were designed to be looked at in well-appointed rooms like libraries and museum galleries . . . [but she made them] for those of us who are entranced by the intricate ways our fantasies, desires, and memories are both personal and public.”

We all benefit from a more inclusive and intersectional feminism, as well as criticism within and across feminist and women-centric organizations, communities, and ideologies. The new anti-abortion law in Texas is a stark reminder that the freedom women have claimed is fragile. As a society, as artists, and as museum patrons, we still require evolution, reinvention, and nuance. However, a clear “Fuck You” to anyone who wants to subjugate women is still squarely in vogue, relevant as long as the political, racial, socioeconomic landscape of a democracy sliding backwards provides the context.