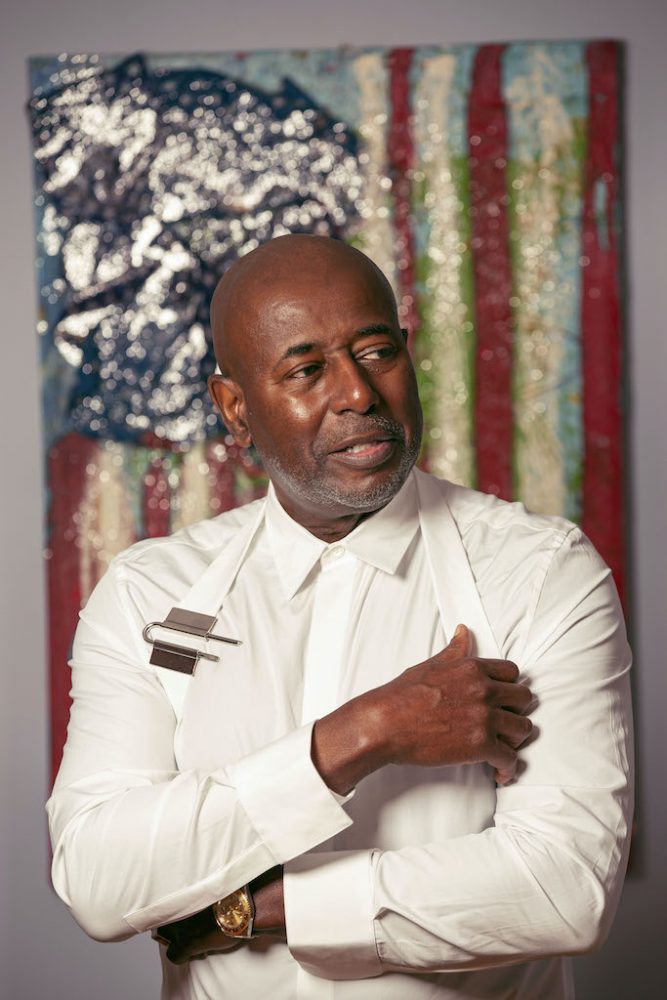

“I buy work based on recommendations. I may go someplace to see art, but I don’t spend a lot of time going to art fairs and that kind of thing,” he says. “My consultant, Jeffrey, if he says, ‘You might like this,’ I’ll say, ‘Oh, okay.’ And I’ll go take a look at it… When I see it, I know.”

Many art market reports are just beginning to capture the growing divides between millennial and next-generation collectors versus experienced art collectors. Points of divergence include the way collectors access art, as well as the type of artwork that they purchase, with younger collectors more willing to procure digital and crypto-artworks including NFTs, whereas experienced ones typically stick with familiar, traditional mediums.

The COVID-19 pandemic greatly influenced the surge in millennial and next-gen collectors purchasing artwork via online platforms and reviewing works solely through their mobile devices, as confirmed by nearly 58 percent of collectors surveyed by a recent Artsy poll. The 2021 Art Market Mid-Year Review conducted by Art Basel revealed similar trends: in 2020, 91 percent of next-gen practitioners procured artwork online, up nearly 40 percent from the previous year.

Most experienced art collectors are still skeptical of this option. I asked Timmons if he would ever consider purchasing NFTs or other digital artworks. “Not yet. I’ve looked at that, and I’ve looked at crypto, and I’m thinking about it. [NFTs] are becoming more prominent now, but I’m not quite ready to get there, ‘cause I’m old school,” he laughs. “I like to touch what I have and know it’s protected. The world is moving that way, but there’s still something about having that art right in front of your face.”

Beyond the immediacy of being able to touch and view precious works of art in one’s home, collectors must also consider the legacy of what they have procured. For Black collectors who hope to donate works from their collections to Black institutions such as HBCUs, many systemic factors play a significant role in their ability to follow through on that desire. If an institution is historically underfunded—because of racism or cultural bias, even though said institution maintains a prestigious name or reputation—a collector may be less likely to donate work to that institution.

Costs associated with the long-term maintenance and archival of collections are a considerable concern for all institutions, but are compounded by histories of financial underinvestment in Black institutions. Just last year, after a 15-year-long struggle, four HBCUs in Maryland finally won a $577 million settlement against the state which was accused of inequitable funding. This battle for equity is a small sample of a nationwide epidemic that complicates collectors’ ability to support Black institutions while also protecting their investments.

I asked Timmons what hopes he had for the future of his collection. “I’ve started to talk to my nieces and nephews about the art world and I think they have an appreciation,” says Timmons, considering the legacy of his art collection. “I may donate some. I may order some to be sold, but I am definitely talking to them about art. They need to understand the world has changed about art, especially Black art. You can help your community and help yourself at the same time.”