Where were you, geographically, creatively, and/or professionally, before attending MICA?

I was living in Gallup, New Mexico, on the border of the Navajo Nation when I started at MICA. I kept a small studio there, overlooking a wide expanse of undeveloped high desert wilderness, populated by pinon and juniper trees, sprawling ant and prairie dog colonies, fox, coyote, wild sunflowers, the occasional herd of free range sheep, and the occasional human on foot or 4×4. My creative practice focused on this interconnected human and nonhuman ecosystem, the more-than-human forces like wind, monsoon, and sun that held power over it, and the capacity of these lifeforms to survive and even heal in physically and socially hostile conditions.

At that time, I was also working as a resident artist in a therapy clinic, helping adolescents and young adults develop art practices of their own as part of a holistic trauma recovery plan, while showing my own work in alternative art spaces, including hospitals, rehab centers, universities, and non-profit art spaces.

Not long before that, I was living in Philadelphia, studying painting and drawing at night, practicing law during the day, and feeling into all the ways art can nourish life, repair wounds, and resist power differently than law.

Why did you select this particular program?

I was looking for a rigorous program where my practice as a socially-engaged artist and thinker, attracted to the sensory immediacy and openness of non-representational art, but resolutely grounded in the vibrant material world, could thrive. I was also looking for a community where my transdisciplinary background as an artist/ attorney/ independent researcher could live as a welcome source of enrichment and perspective among similarly multi-faceted artists.

I got both in MFAST. I found a culture of inclusive rigor that empowers students as valuable critical voices and sources of wisdom, capable of giving and receiving thoughtful critique. I also found a profoundly transdisciplinary community, unique among the programs I encountered.

During my time in MFAST, for example, my peers have included a Traditional Chinese Medicine doctor, a trauma nurse, an experimental poet, an international curator, a mathematician, a housing rights advocate, a sheep farmer, a glass blower, a queer documentary filmmaker, a fashion designer, and a war journalist. All are encouraged to add their perspectives to the discursive breath of the community, without any real regard for the edges of what we might think of as “art.” This is exactly what I wanted.

As an artist who already had a fairly developed independent studio practice before grad school, I also valued the independence and geographic flexibility that MFAST afforded me, alongside repeated intensive periods of highly focused critique, engagement, and growth.

What have you learned from living in Baltimore? How has your perception of the city changed – from before MICA until now?

I have found Baltimore to be a model of resiliency and of the possibility for repair and adaptability, even in the midst of ongoing traumas. I was particularly moved by the spirit of survival and the will to grow some piece of sovereignty and community among the host of urban farmers I met while helping teach a section of Baltimore Urban Farms with Professor Hugh Pocock. The drive to reconnect with the earth where it is and how it is and to grow something, however small and fleeting, echoes much of the spirit of my practice. I felt deeply how these gestures of renewal and return can become seeds of hope in an almost hopeless time, even if the carrot we grow comes out gnarly and stunted, and even if that carrot can only feed one person part of one meal.

I will also never forget walking by the Black Trans Lives Matter mural painted across the entire width and length of a block of North Charles Street everyday during the summer of 2021. This monumental street art hit home for me then, as a trans person, and reverberates even harder now as we face down an unprecedented cascade of anti-trans legislation across the United States.

This summer, I was similarly greeted by a full window of hand-printed posters broadcasting “Protect Trans Kids” from the MICA screen printing building. These are small gestures of support, but they make Baltimore feel like a refuge city for trans people in an era when the list of States I am actively boycotting as anti-trans hellscapes because they have criminalized gender-affirming care for trans youth has grown to 18 in less than 6 months (AR, FL, GA, ID, IN, IA, KY, MS, MO, MT, NE, ND, OK, SD, TN, TX, UT, WV).

Tell us about your work. What are your primary materials? What are the main concepts you explore in the work? How do your materials and concepts intersect?

My practice centers on a colony of styrofoam-metabolizing mealworms and other pollution-consuming nonhuman agents (like mycorrhizal fungi and sunflowers) who slowly metabolize heaps of human industrial and consumer waste, breaking the materials down into biodegradable components capable of being reworked into new life. As is fitting for work about metamorphosis and the plasticity of matter, the work has no fixed form or medium, adapting to the dynamics of different spaces and entangling itself within the structures it encounters, but it is most often shown as living sculpture within immersive multisensory installations of metamorphosis-friendly colored light and sound, which incorporate and act upon the human “viewer” as much as the nonhuman “objects” of the human gaze.

I think of the work as having conceptual layers that reveal themselves to the viewer/participant over time. The first, most literal layer, implicates human overconsumption, the toxic legacies of consumer capitalism, and the relative power, beauty, and worth of the lowly mealworm. On this level, I think of the work as an effort to “stay with the trouble” (as Donna Haraway would say) and think beyond human-centric norms about what is precious, what is beautiful, and what is possible.

In a world where trans people and others are routinely dehumanized as dirty, sinful, and insect-like, I’m also thinking about the metaphorical resonance of this work, which centers the healing power and resiliency of metamorphosing creatures, and how it subverts traditional ideas about the sacred and the profane. I use materials that are associated with the sacred in Catholic and other religious traditions, including egg tempera, cast chromatic light, essential oils, translucent veils, and water, as a way of asking: Who and what deserves our reverence now? Who and what is really profane, invasive, contaminating? Who, if anyone, is going to come save us from the consequences of our own destructive behaviors?

Dirt is also an important material in my practice, with all of its associations with impurity, filth, and lust/pleasure. I work with site-specific dirt and municipal mulch, test the soil, and combine it with the seeds of its own repair. These living sculptures become demonstrations of the power of fungi over human toxicity, but they also show the possibility of a kind of muddy healing that does not desire purity or glorify transparency.

What is the title of your thesis show? Please give us a sense of depth and breadth of the show, where it is, and how you want it to resonate with viewers?

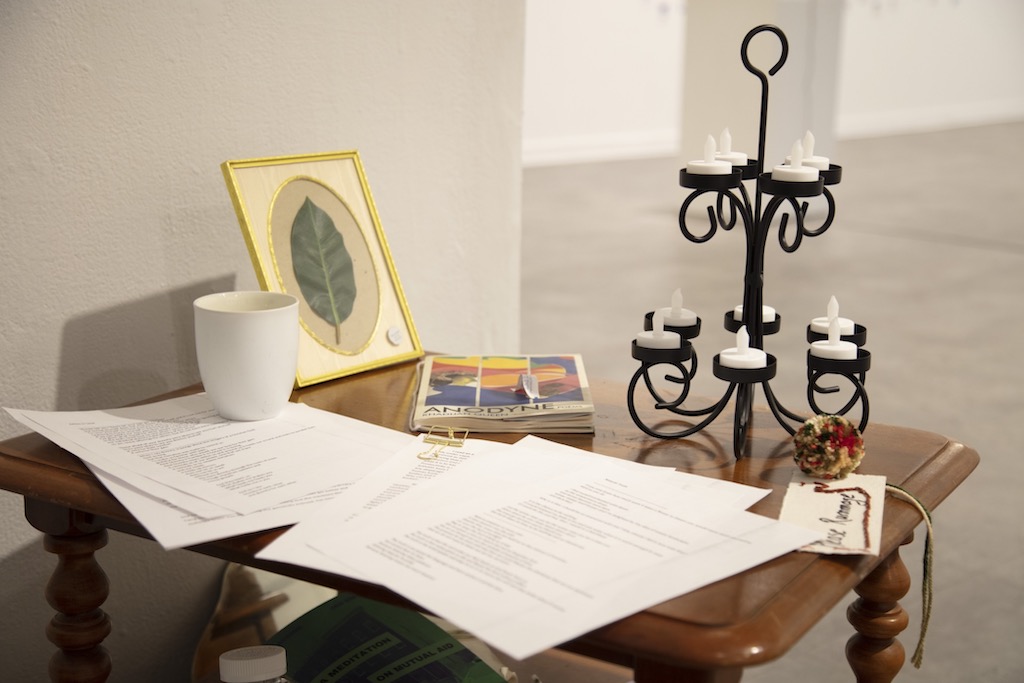

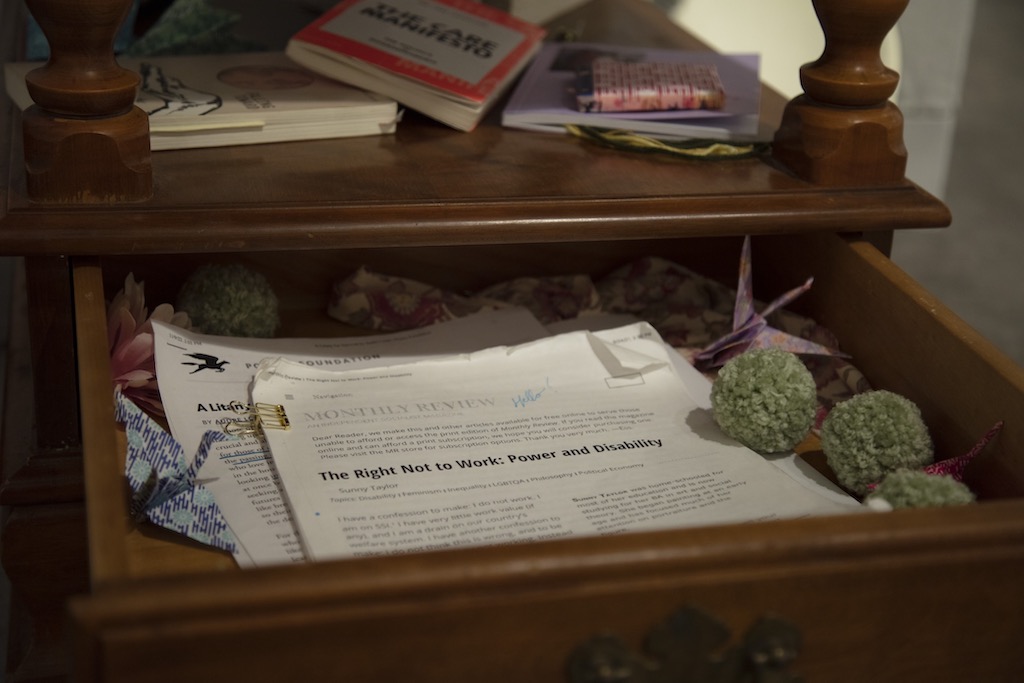

My thesis show is titled: Womb/Tomb/BooM – A Multisensory Refuge for Plastic Bodies. It is up through July 9th in the Meyerhoff Gallery on the First Floor of the Fox Building on MICA’s main campus. I will also be giving a public talk as part of this exhibition on July 6th at 11am in the Lazarus Center’s auditorium.

The show includes my largest and most ambitious interspecies installation to date: a 20 x 17 x 15’ resonating architectural chamber lit entirely in metamorphosis-friendly cast magenta and purple light. All four walls of the darkened chamber and part of the ceiling resonate with the live sound of more than 10,000 mealworms consuming and metabolizing styrofoam.

In the center of the chamber lies a 80 x 60” worm bed composed of pine, aluminum flashing, and vinyl that houses a human-scaled architectonic cityscape of living and disintegrating styrofoam structures. Insects in both their larval and beetle form are visible consuming and burrowing in and out of this styrofoam material behind a draped veil of hand-sewn mosquito netting, which stretches up to the ceiling like a canopy over a human bed or a veil over a shrine. The space is designed to provide the mealworms with the most beneficial environment possible, while also positioning the “viewer” as a part of the system, i.e., a participant in this process of metamorphosis, who may be consumed and metabolized by it as much as they may consume and metabolize it.

The space is also meant as a refuge for all kinds of plastic bodies, including styrofoam itself, the mealworm insects (whose bodies undergo “complete metamorphosis” shifting shape from egg, to larvae, to pupa, to beetle), and all humans with “plastic” forms, including trans people and anyone else who might think of their body as fluid and changeable. I want the space to operate as a sensory refuge for these bodies – a place that might disturb the comfortable (i.e. those who are accustomed to a comfortable sense of embodiment and/or the anthropocentric notion of humanity’s inherent superiority over the nonhuman) and comfort the disturbed. I’m particularly interested in the ways that this refuge space might protect or comfort vulnerable beings by reducing the legibility of the visual and auditory senses, frustrating the otherwise ever-present, dissecting cisgender gaze.

In an adjacent fully lit, 3-sided room, a “dirty” bath holds a living heap of bound, biomorphic burlap sacks, stuffed with inoculated mulch and phytoremediating sprouts, confronting viewers with a queer experience of cleanliness emerging from dirtiness – abjection birthing (dis)repair.

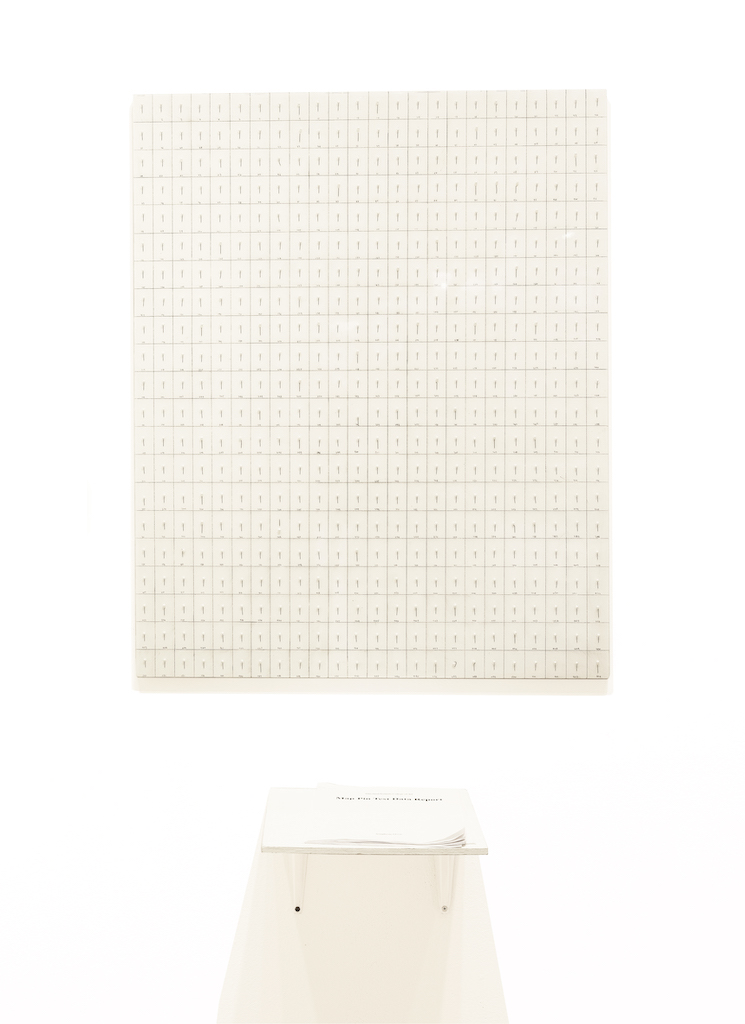

The show also includes a new series of layered, language-based works on transparent acrylic, which bring together the marks of pollution-consuming insects, fungi, and my own hand as we deface, remix, and reclaim the visual and semiotic material of toxic legal artifacts for our own pleasure.