As this column launches on January 28, 2024, crowds are gathering across Cuba, the annual Ofrecimiento en Central Park is beckoning New Yorkers, and the City of Miami Beach is preparing hundreds of pastelitos and cups of coffee, all to celebrate the birthday of the man known as the “Apostle of Cuban Independence”—José Julián Martí Pérez, born January 28, 1853. Some of these events entail visitors placing white roses at the base of their local public sculpture of this figure. Why?

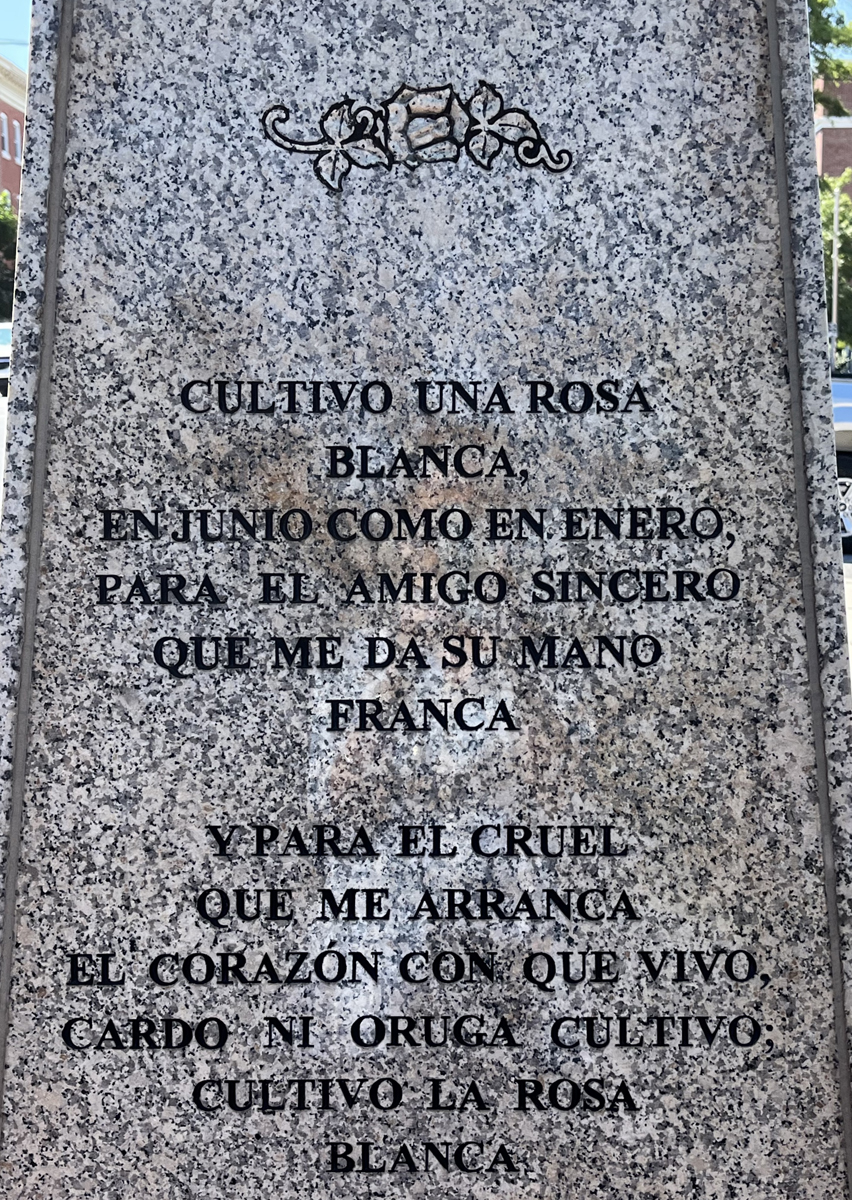

José Martí was not only a fierce leader of political thought and action for Cuba’s independence from Spain, but a philosopher, professor, publisher, journalist, translator, essayist—and poet. It’s one of his most well-known poems that prompts the ceremonious placement of such a particular flower at public tributes to him on this day:

I have a white rose to tend

In July as in January;

I give it to the true friend

Who offers his frank hand to me.

And for the cruel one whose blows

Break the heart by which I live,

Thistle nor thorn do I give:

For him, too, I have a white rose.

~ José Martí, Cultivo una Rosa Blanca… (Verso XXXIX)

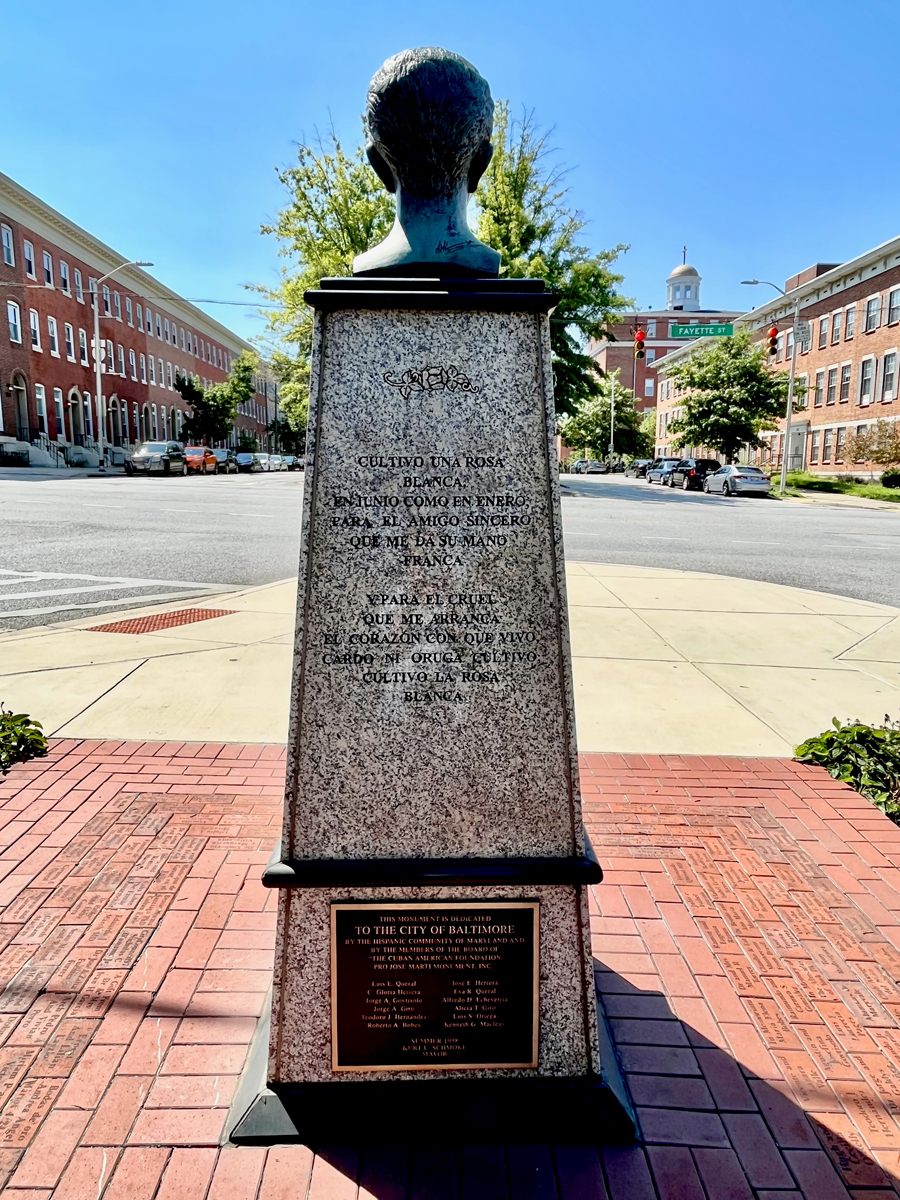

This verse is carved into the back of the granite base that supports a bronze bust of José Martí, sculpted by Afro-Cuban sculptor Teodoro Ramos Blanco, right here in Baltimore, located on the North Broadway median strip alongside the Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Skip Viragh Outpatient Cancer Building, at the corner of East Fayette Street. This public sculpture has been with us since its unveiling in “Summer 1998,” as one of the bronze plaques on the work’s base tells us.

When I mentioned to friends that I was writing about this work, several said they’ve walked by it many times but never really stopped to take in the whole monument. Such a response is not unusual when it comes to public art, especially works like Baltimore’s José Martí, which involves carved words and informational plaques that require more than a glance.

Maybe our task as public art viewers involves both story-finding and story-making. Either way, we are the owners of the outcome.

One of the goals for this new monthly BmoreArt column on public art is to shine a light on the multitude of stories that any public artwork holds. Baltimore’s Martí is a good starting place—and, in fact, serves as a kind of table of contents for how we might look at public art—because the first level of stories is overt, appearing right there on the surfaces of the four sides of the base holding up Martí’s bust. Not that abstract works, with their curved, geometric, colorful, mixed media features don’t offer this first level of storytelling surfaces; it’s just a different type of information, which will be discussed as the months of this column proceed.

With a little digging on the part of any passerby, prompted by the cues these surfaces offer, other levels of stories start generating, then proliferate, and become infused with the curious viewer’s own thoughts and sensations. This series of intertwining cognitive and phenomenological events begins the moment the viewer decides to do some digging, gains energy through each moment of discovery, and culminates in a rich amalgam of stories comprising a narrative the researcher then owns. This narrative mix of facts and feelings ultimately tells us something about ourselves as humans and as community members—whether that community is made up of neighbors or a group of tourists just passing through.

Moreover, because what we’re talking about is public art, we “own” the actual material object that started this journey of story-finding in the first place and that ultimately yields such an alchemical result. What a wondrous venture. And best of all? It’s all free—the actual piece, the search and discovery, and the culminating narrative. For that’s one of the core elements of public art: Ownership.

Despite one often-vexing layer of stories—about who owns the land on which the piece sits, whose collection it resides in, how it will be maintained (or not), whether it will remain (or not)—the public art piece is ours, as long as it stands and (really) even if and when it disappears. More on all these points as the stories of Baltimore’s Martí, as well as this monthly column, continue.

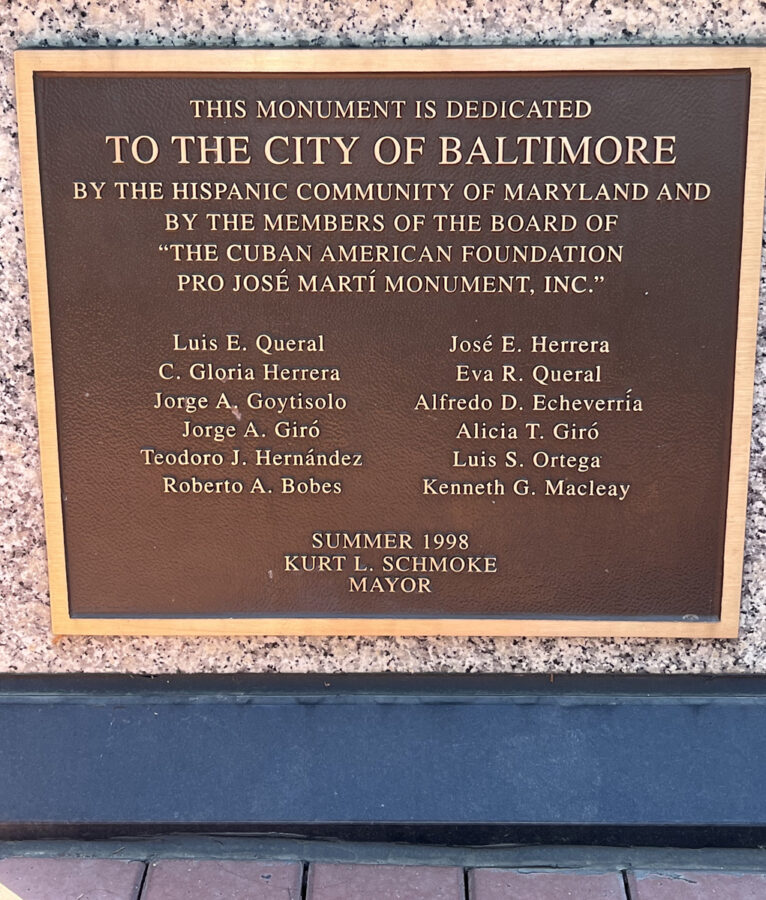

Getting back to the back of the granite base upholding Martí’s bust: Situated below the carved poem is a bronze dedication plaque with thirteen names. Twelve were Board members of “The Cuban American Foundation Pro José Martí Monument, Inc.,” the plaque indicates; the thirteenth was Mayor Kurt Schmoke. Sadly, a number of the Board members are now deceased. From all accounts, one of them, Dr. Louis Queral, appears to have led the project. After leaving Cuba in 1957, he’d ended up in Baltimore, practiced plastic surgery here, and was an inspiring community organizer and leader whose associates were sometimes referred to as “Queral’s people.”

So inspired by Martí, Queral kept his hero’s books in his office, along with medical publications, plus a painting depicting Martí’s death on May 19, 1895, that Queral himself had painted. In keeping with Martí’s model of cultural engagement, the doctor was also a publisher, having founded El Mensajero, a monthly publication that was still going 30 years later, when he died in 2010. Not surprisingly, he also followed Martí’s political activism, using the Martí monument, less than one year after its unveiling, as a rallying point for a peaceful protest, which he organized in opposition to the Baltimore Orioles’ hosting a game with Cuba’s national baseball team in April 1999.

Hundreds of participants from as far away as New Jersey and Miami joined Marylanders at the Martí monument, then walked or rode to Camden Yards. (This would be far from the last time the artwork would play a role in activism. As I completed this column, flyers were circulating for “Shut it Down! For Palestine March & Rally,” starting at the “José Martí Monument” yesterday, January 27.)

It took indefatigable efforts on the parts of several Board members listed on the plaque—especially Board treasurer Gloria Herrera and her husband José, both now deceased—to get approvals and find a site for the Martí sculpture. When the corner of East Fayette and North Broadway was secured, it seemed appropriate, given its proximity to neighborhoods where a community of immigrants from Latin American countries was burgeoning. In advance of the unveiling, the Baltimore Sun called the Martí sculpture “a signpost of a new ethnic era in East Baltimore.”

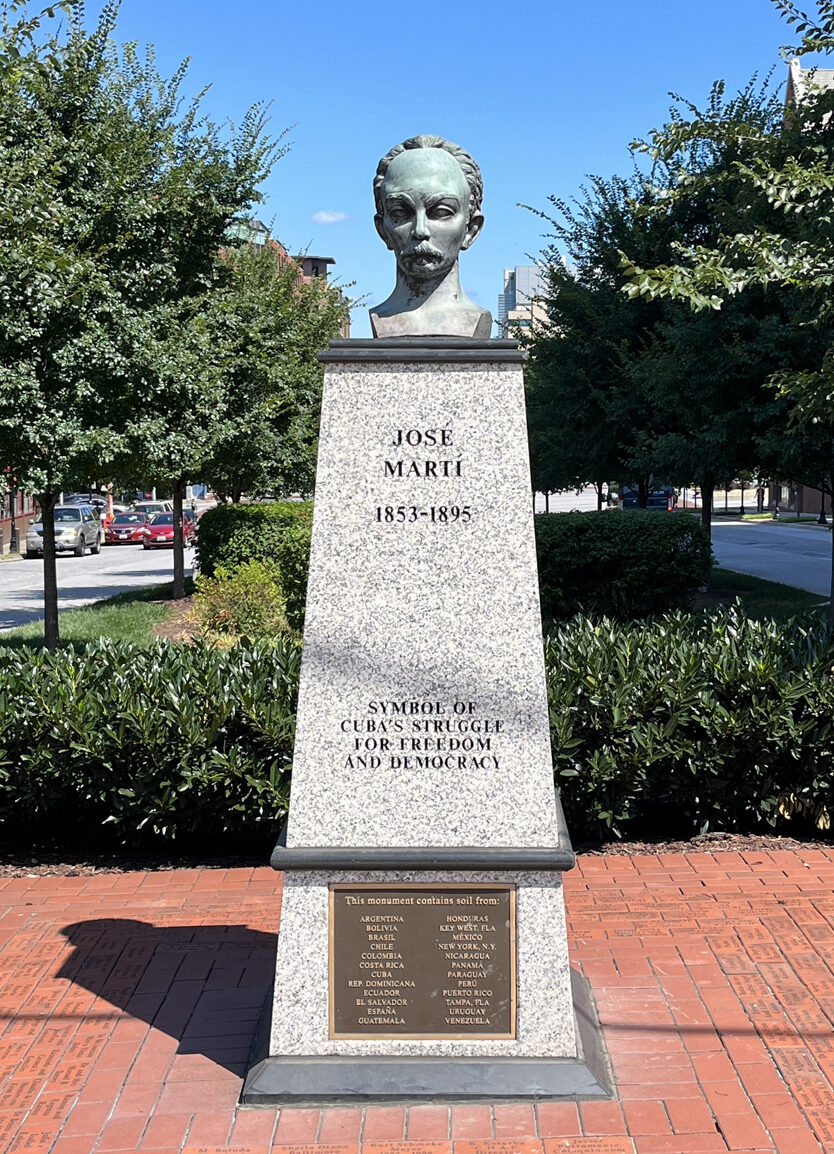

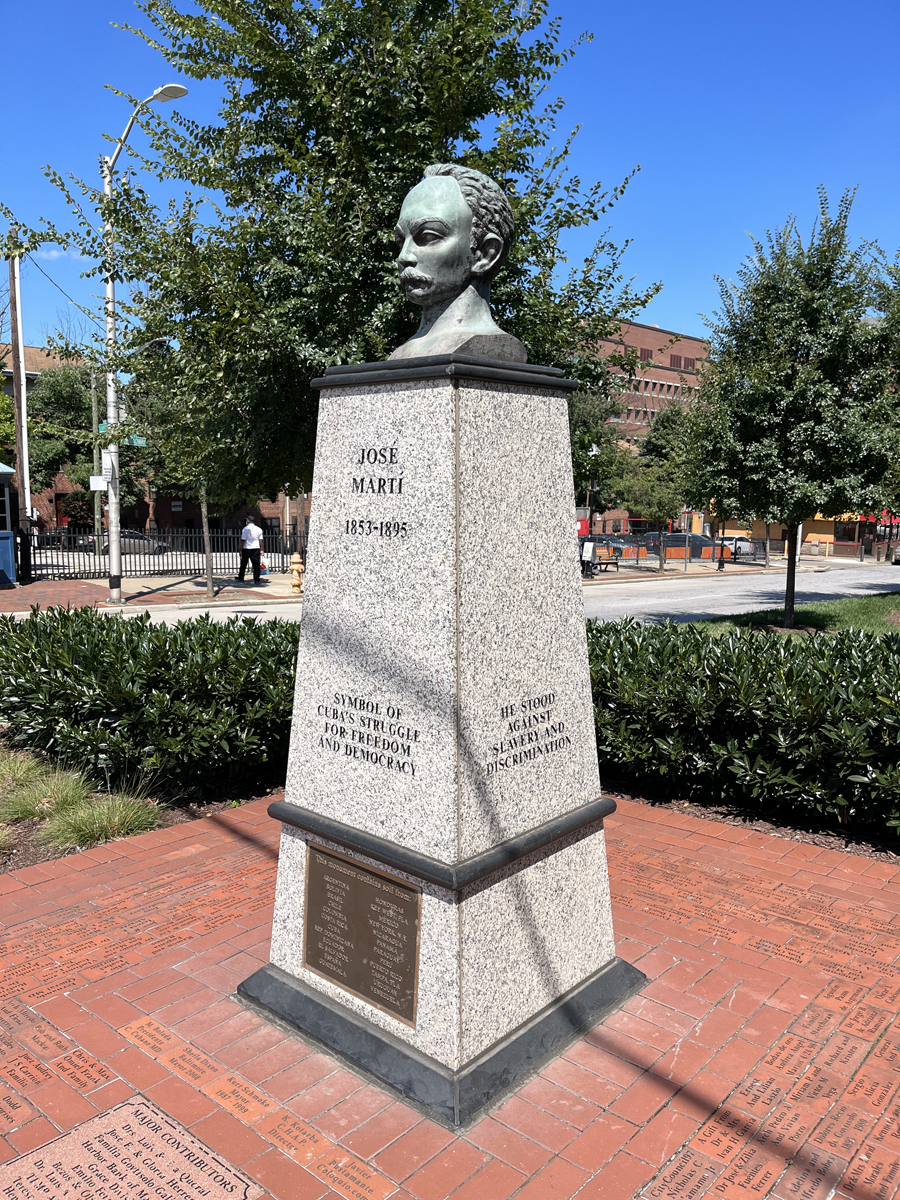

Each of the other three sides of the granite base features carved wording, as well: HE LOVED HIS COUNTRY AS HE LOVED THE AMERICAS on the west side; HE STOOD AGAINST SLAVERY AND DISCRIMINATION on the east; and SYMBOL OF CUBA’S STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM & DEMOCRACY on the south-facing front of the monument, below Martí’s name, birth, and death dates.

Baltimore’s likeness of Martí, like those in some other locations around the world, is just a bust. And I like that. For there would not have been any of his writings had it not been for his extraordinary mind.

It was Martí’s writings that first got him into trouble. At age sixteen, already sensitized to Cuba’s social and political issues, including slavery, by quietly nationalist teachers at his school, he wrote a letter to a friend who’d just joined the Spanish army, rebuking him for enlisting.

The letter was intercepted by authorities and landed Martí in prison. The accusation was treason, the sentence six years hard labor. After two years, his health having dangerously deteriorated (he would suffer lifelong ailments from the iron chains and ankle cuffs he had to wear while working in the nearby lime quarries), his parents and family friends managed to get him transferred. Authorities eventually exiled him to Spain, hoping that schooling there would instill in him a devotion to Spain.

But Martí’s abhorrence for the colonizers of his country only deepened. His writing flourished as he traveled to numerous countries, earned degrees in liberal arts and law, founded publications, taught, and expanded his circle of abolitionist, anti-colonialist friends. With several of these colleagues, he returned to Cuba to help secure its freedom after the failures of the Ten Years’ Wars (1868-78) and the Little War (1879-1880). Landing in April 1895, two months into the ultimately successful War of Independence (or The Necessary War, as Cubans call it), the group joined the Cuban rebels.

Martí, who had never fought in combat and had been reproached by some for that lack of experience, was killed almost immediately in his first battle. Three-and-a-half years later, in December 1898, Cuba was finally free from Spanish rule.

Some monuments to Martí in the more than two dozen locations around the world where they reside—ranging from expected locations like Cuba, Argentina, Peru, Mexico, Spain, and US cities like Miami Beach, Houston, and New York, to less expected locations like Australia, Bulgaria, India, and US cities like Shiveley, Kentucky (this list is far from complete)—are equestrian. One of them, New York City’s Central Park monument by sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington (she was 81 when she created the work), features Martí on horseback. In this case, the horse is rearing, Martí’s brow is furrowed, his arm pressed against his side, representing the fatal moment of his entry into battle.

Baltimore’s likeness of Martí, like those in some other locations around the world, is just a bust. And I like that. For there would not have been any of his writings had it not been for his extraordinary mind. That philosophical, political, poetic brain, housed inside that big, bronzed forehead, looms above viewers from atop its granite base in Baltimore, seeming to send propitious signals to Martí’s eyes, which stare ahead, looking steadfastly to the future. His mouth turns slightly downward beneath the heft of his mustache, lending gravity to his presence that might otherwise have been lost to the sinewy physicality of a horse or even the intricacies of clothing in some of the full-figure statues that exist in other locations.

I’m proud of Baltimore’s success, back in the mid-late 1990s, in mounting this public artwork, and grateful to all those whose names appear on the dedication plaque and to all others who have cared for this piece. Among the latter is Cindy Kelly, the grande dame of Baltimore’s history of public art, who documented in her book—Outdoor Sculpture in Baltimore: A Historical Guide to Public Art in the Monumental City—more than 250 public art pieces at the time of its publication in 2011, including the Martí monument.

The potential for haze when tracking the stories of public art is, for me, part of its attraction, made even more challenging when the work can be replicated. We’ll probably never know where Blanco’s “original” bust of Martí is. And what is an original bust, anyway?

From Kelly’s account, Martí’s bust was sculpted by Cuban artist Teodoro Ramos Blanco sometime before 1959 and came to Baltimore by way of Miami, where an acquaintance of Dr. Queral’s had “brought it from Cuba years before” and sold it to the doctor for the Baltimore project. Ada Ferrer, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book Cuba: An American History (2021), has a slightly different, hazier account of Blanco having donated the bust to Baltimore. I trust Kelly’s account, because I suspect she discovered her details in City documents and/or through Dr. Queral’s family or community.

It’s worth noting that the sculptor’s name appears nowhere on the monument, an absence that’s not uncommon in the world of public art. Nor did the Baltimore Sun’s article about its unveiling mention his name. This feature of assumed anonymity (another topic for future columns) thickens the haze.

The potential for haze when tracking the stories of public art is, for me, part of its attraction, made even more challenging when the work can be replicated. We’ll probably never know where Blanco’s “original” bust of Martí is. And what is an original bust, anyway? When it comes to casts, the original would likely have been clay, which would likely have been destroyed during the process of making the mold for casting in bronze. There could have been an inaugural cast, of course, and if so, it’s likely in Cuba – maybe Blanco’s bust of Martí that’s just like Baltimore’s and lives at a site called Martí’s Forge in Havana, or the same bust that looks down from the second-floor balcony at the Provincial Library Rubén Martinez Villa in Sancti Spíritus, Cuba. Wait. The latter is carved in stone and signed by Blanco, so is that the original? Questions accumulate. More seek-and-discover is required. More stories to find.

My last two stories bring me back to the (perhaps debatable) question of ownership discussed at the beginning of this column. One took place in September 2016, when the Martí monument appeared to have gone missing. Then-Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake’s office had to reply to a since-retracted, scandal-provoking post on the Facebook page of the newspaper Latin Opinion Baltimore that read: “Decapitan a José Martí en Baltimore y nadie dice nada [Beheading of José Martí in Baltimore and no one says anything].” Other residents were outraged, as well.

The Mayor’s office replied: “This was a temporary and planned removal of the monument, in order to preserve it from damage that construction could cause…. It’s not destroyed. We’re protecting it” (rough Spanish-English translation). Indeed, the Skip Viragh Outpatient Cancer Building was being built, so the monument was put in storage to prevent damage.

The Mayor’s office did the right thing as owners/stewards. Even though their communication skills were on backorder, the outcome was better than the situations the Baltimore Banner reported in its 2023 story titled “More than a dozen public art pieces have vanished. Not a single person can say why.” More to come on this topic in future columns.

The other story is a personal one, about the alchemy I mentioned at the beginning of this column. The cognitive-phenomenological interface for me kicked in the first time I visited this piece, as I studied the words on the bronze plaque at the bottom of the granite base’s front side: “This monument contains soil from,” followed by a list of twenty-four locations around the world, twenty-one of them Latin American countries, plus Spain and two US cities—New York City and Tampa, Florida. I was transfixed.

Goosebumps rose as I made up a story in my head that entailed all these locations being the home countries and cities of now-Baltimoreans who’d helped with this project. I imagined a young woman writing to her grandmother “back home,” asking her to go to the family garden, dig up a spoonful of soil, put it in an envelope, and send it to her granddaughter so she could fold it into the earth beneath the base of the sculpture.

It was a lovely story, homing in on the fact that I come from a long line of farmers for whom soil is a valued and very storied entity. Alas, Kelly’s book set me straight. The soil samples came from each of the countries and cities where Martí had lived. I guess that doesn’t totally shatter my story. After all, tablespoons and envelopes could have been involved, right? But the truth is, per Kelly, the soil samples were all placed in an urn, which was placed inside the granite base. That story is lovely, too. So, maybe our task as public art viewers involves both story-finding and story-making. Either way, we are the owners of the outcome.

Happy Birthday, José Martí. May this column serve as my white rose.