I have known artist and educator Pablo Helguera for many years, during which I’ve enjoyed his playful approach to art and art spaces, and his serious approach to play. I have seen him organize experimental educational programs at major museums and art institutions, such as the 2011 “Art Speech: A Symposium on Symposia” (with James Elkins) at MoMA, a sort of metacommentary on the forms and conventions of art scholarship and public presentation.

That event included a live deconstruction of a lecture by art historian T.J. Clark and a critical evaluation of MoMA audio guides (other symposia organized by Helguera as an educator at MoMA took even more expanded and playful formats, including a Colombian party bus that he chartered for a 2009 symposium on “Transpedagogy”).

In 2013, I was in the audience for his scripted panel discussion at the College Art Association annual meeting, which reimagined the conference as a performance space with actors reading a script authored by Helguera and collaborators. And in February of last year (2023), I attended his Untitled (Comedy Show) performance featuring artist Martha Rosler, a full off-broadway performance and talk show in an NYC dinner theater venue, which was rounded out by an art trivia game show activity and small audience prizes to take away.

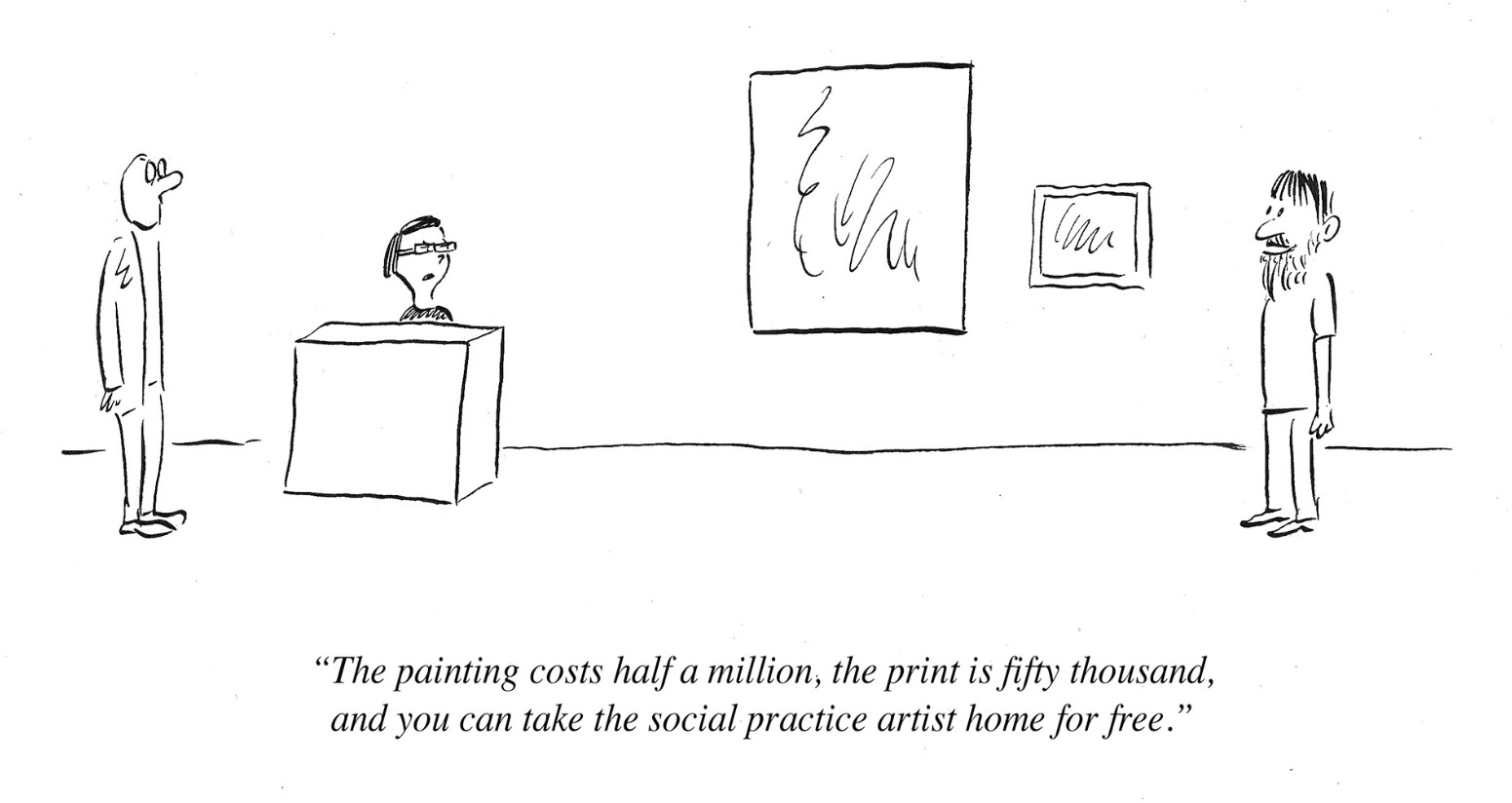

In all of these endeavors, Helguera integrates playful formats with serious topics, and shows how art—which, at least in principle, should be a playful and experimental discipline—is so frequently limited to presentation spaces defined by rigid protocols. Helguera’s work intentionally defies those expectations and challenges those norms.

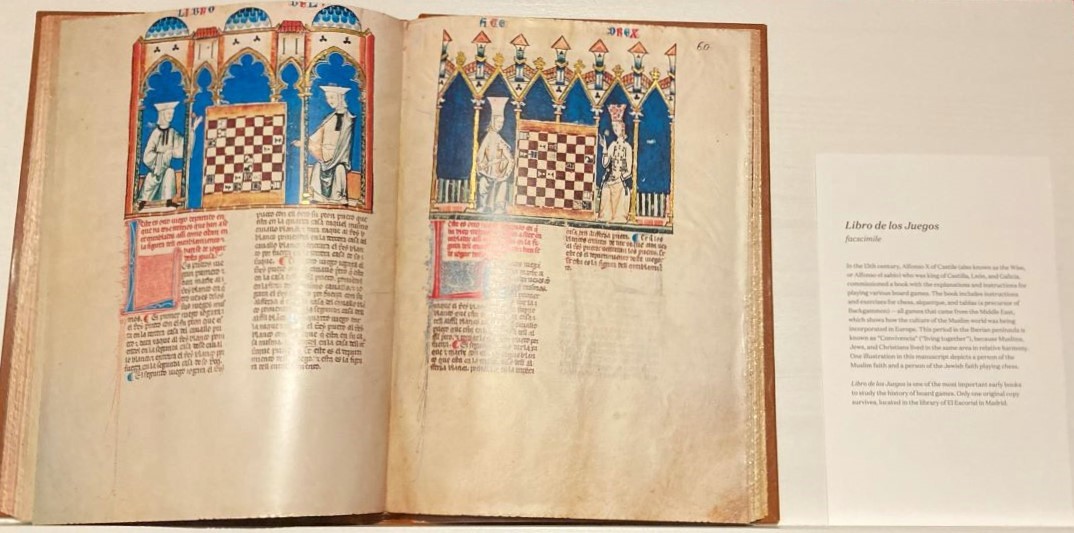

I admire his practice, both in art and education, and his inventive and creative approach to pedagogy and learning. That is why I was excited to get to speak with Helguera about his new work Flor de Juegos Antiguos (Flower of Ancient Games) (2023), created for a recently-opened group presentation at the Baltimore Museum of Art’s new Joseph Education Center Experience Gallery.