“Things are better now than they ever have been for women and artists of color,” says the Guerrilla Girls, the outspoken experts on equality in the art world. “Right now there is decent representation of women and artists of color at the beginning and emerging levels of the art world. At the institutional level however, in museums, major collections and auctions sales, things are still pretty dismal for all but white guys.”

On their current website, the masked, feminist avengers blame the economics of the art market for the imbalance that still favors white male artists in major museums and blue chip galleries. The National Museum of Women in the Arts corroborates these claims, estimating that five percent of art currently on display in US museums was made by women.

Although the Baltimore Museum of Art prominently and proudly features a number of white male artists in its contemporary wing, with Warhol, Stella, Guston, and Rauschenberg placed in plumb spots, the newly opening Contemporary Wing features an early Grace Hartigan abstraction, a square Elizabeth Murray painting, two Anne Truitt sculptures, a series of prints by Joyce Scott, a Jenny Holzer text piece, and a number of other works by female artists and artists of color, all from the museum’s vast collection.

As the beloved regional museum charts a new course, beginning with its newly renovated Contemporary Wing opening on November 18, 2012, it’s promising to see a strong emphasis on female artists and artists of color. While many museums are still mired in the politics the Guerrilla Girls describe, the BMA is leagues ahead. This is most telling in the newest acquisitions purchased for the grand re-opening on display throughout the gallery. Not only has the museum selected a number of women and artists of color for its permanent collection, many of them are forty and under, an insightful, daring, and heartening agenda. From the number of significant new acquisitions, I have selected five works at the forefront of the BMA’s new direction.

Sarah Oppenheimer, American born 1972

W-120301 and P-010100, 2012, Two Architectural Interventions

It’s one thing to purchase an experimental work of art by a young artist but quite another for the artist to cut through the walls of the museum’s holiest of holies, The Cone Collection. The BMA takes this a step further, as the first major museum to commission a site-specific installation by New York artist Sarah Oppenheimer, a visionary on the cutting edge, literally, of international fame.

Oppenheimer’s installations involve slicing through walls and inserting aluminum panels and reflective glass to create a dramatic, periscope effect, where you gaze through a window and see surprising views of the gallery in all directions.

Instead of seeing what’s above you, for example, you see the people and the artwork upside down, reflected in the mirrors at varying depths. The effect is disconcertingly magical, like the jolting sense of motion experienced while sitting still in traffic, as other vehicles move around you. Elegant and more subtly crafted than you would expect, the two installations will be enjoyed by small children, snooty artists, and even the most ardent Cone Collection fans. Not only do the sculptures address issues of borders, architecture, and personal space, they create visual connections between works of art, previously separated by style and time period. It may also prove ideal for stealthy people watching.

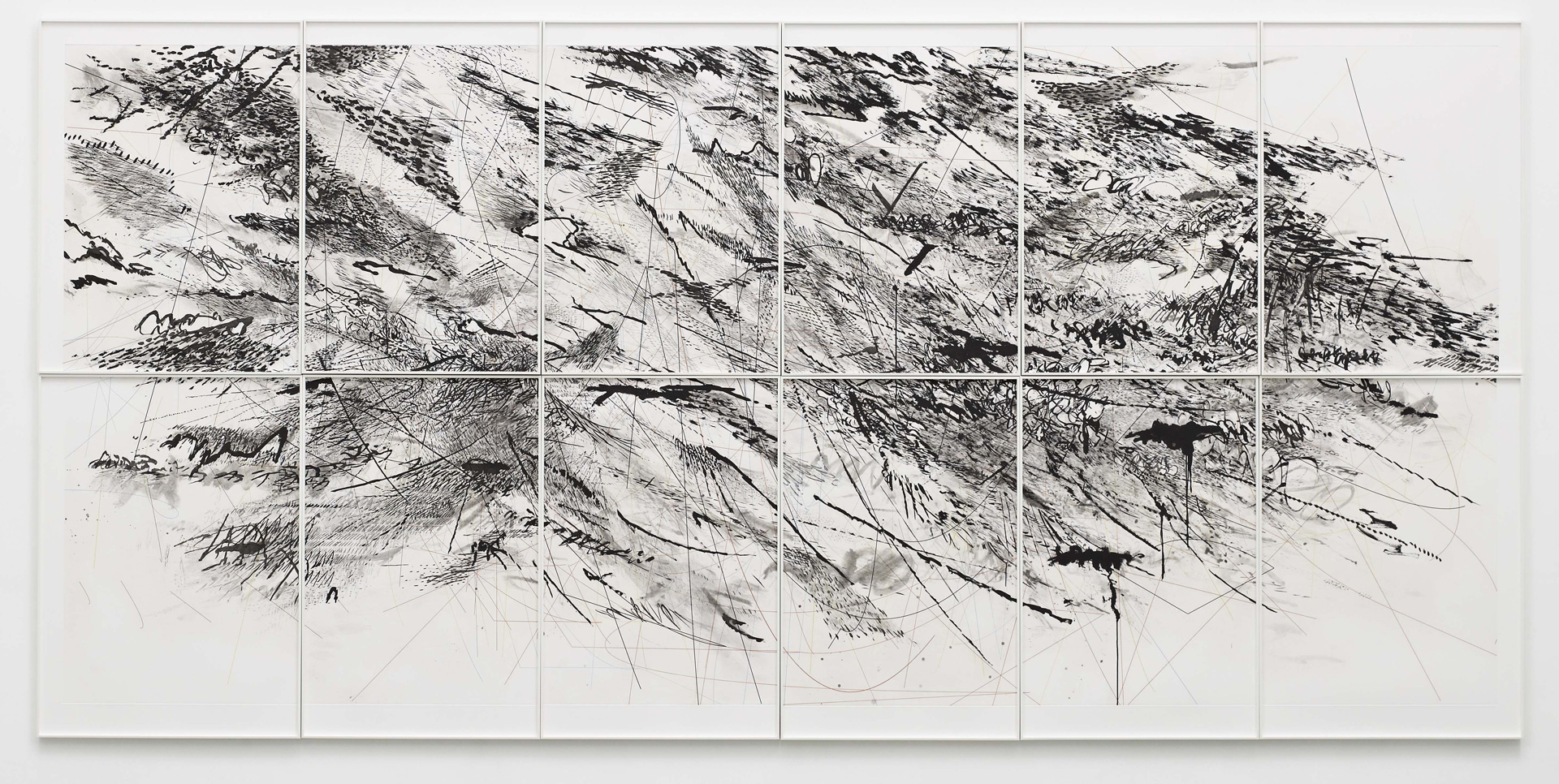

Julie Mehretu, American born in Ethiopia, 1970

Auguries, 2010, a 12- part color etching with liftground aquatint

If you’ve ever wondered why so much work by young artists relates to converging maps and architectural systems, look no further than Julie Mehretu. Her monumental images reference nature, musical orchestration, and the technological interconnectivity of the virtual world through a vocabulary that is abstract, original, and densely accumulative.

Mehretu’s paintings, prints, and installations distill and capture what is most elusive about contemporary relationships – between individuals, social groups, and global entities. More than any other working artist today, her works summarize the experience of living in the 21st century. The artist manages this in an inclusive visual language that avoids judgement, aggression, or didacticism. In short, Mehretu’s works are fresh, perplexing, ambiguous, and visceral.

Auguries, created in 2010, is a grid of twelve prints that reads together as a classic Mehretu image – it is grandiose in size, spare in color, and incredibly dense with thousands of minute elements swimming in barren space. It resembles a “great scarf of birds,” caught in the delirious brink of fragmentation or coalescence. Placed in a gallery with the Eliasson, Kelly, LeWitt, and Judd, the Mehretu holds its own and engages confidently in the solid, monochromatic banter that populates the room.

Susan Philipsz, Scottish, born 1965

The Shallow Sea, 2010, Sound Installation, 1:15 min. recording, followed by 8:00 min. of silence

Susan Philipsz shocked the art world after winning The Turner Prize in 2010. Compared with her painting and sculpting competitors, Philipsz’s sound installations are elusive, verging on intangible. Philipsz projects the sound of her own warbley voice singing different songs a Capella into various public spaces, from bus stations to supermarkets to art museums. Lowlands, the piece that won the Turner Prize and was exhibited at the Tate Modern in London, was originally played under three different bridges in Glasgow. Her choices in music veer from 15th century Scottish laments, to historic Irish and American folk ballads, to more modern choices, such as Nirvana and The Velvet Underground. On the whole, Philipsz’s voice is mournful. Hearing it in an art gallery is disconcerting and over-the-top melodramatic, but not completely displeasing.

The BMA has purchased Philipsz’s The Shallow Sea, a recording of the artist singing Oh willow waly, a love ballad composed for The Innocents, a 1961 film based on Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw. It’s the story of children being haunted by the ghosts of two lovers, so it’s dirgey quality is in keeping with Philipsz’s established aural aesthetic. As a neat visual reminder, the BMA has installed large, round speakers in a vertical formation, so that the piece can be heard from the rotunda, while you are daydreaming through the giant garden-facing glass windows. Although some museum visitors may think this piece is silly and wonder how much it cost, The Shallow Sea is an important work that challenges contemporary art by way of its content and use of media. On one hand, it emphasizes traditional storytelling methods and connects us to the past, while, on the other, it charts a course for the future use of new media and generates more options for artists working outside traditional genres.

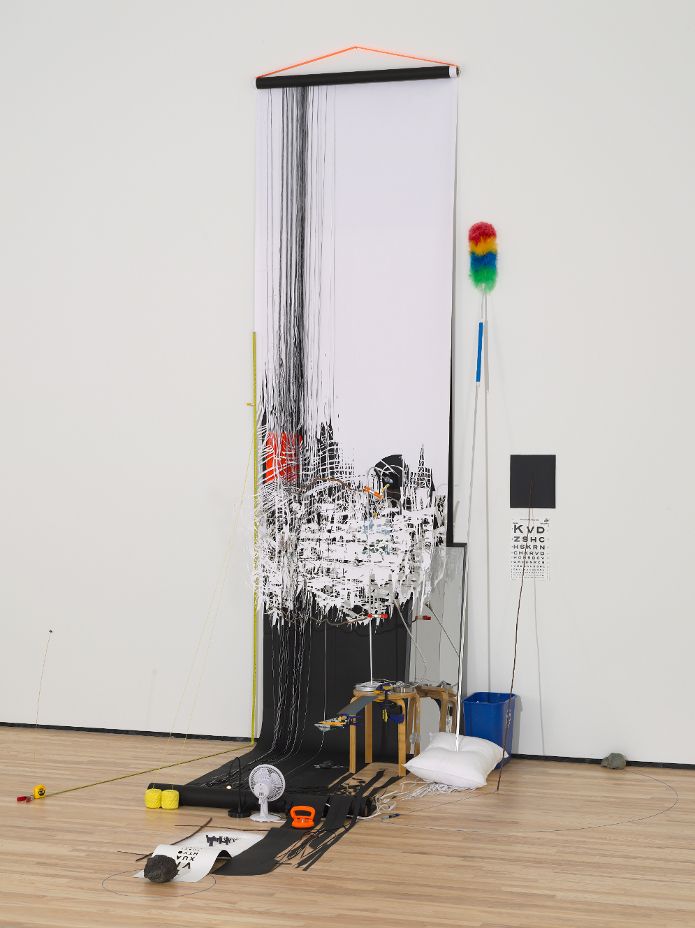

Sarah Sze, American, born 1969

Random Walk Drawing (Eye Chart), 2011, Mixed media

If you have seen the toothpick model of the Titanic at AVAM, and you love it, you will love the work of Sarah Sze. The New York-based artist has built a reputation for herself by compiling tens of thousands of disparate materials, much of it garbage, into unexpectedly elegant constructions. Always theatrical, Sze’s sculptural installations achieve a high level of drama through contrasting visual elements, sheer accumulation, and gonzo constructions of fragile ephemera, which teeter on the brink of collapse. They manage to reference traditional Asian Sumi Ink drawings, optical illusions, and a whole host of hoarder-based OCD behaviors. Surprisingly, they also manage to be aesthetically balanced and even beautiful.

Random Walk Drawing (Eye Chart) is a long, vertical tableau that spills from the wall out onto the floor, like a scroll. The installation includes digitally cut paper, lines of string, cotton balls, eye charts, and a number of other disparate items collected out of doors, on a walk. Elements are mostly arranged by color, so, from a distance, the piece appears unified as a harmonious network. As you approach, the order breaks down into a curious array of incongruous textures, with unrelated, throwaway items placed side by side, in relationship yet maintaining their individuality. A printed eye chart lies on the floor in the midst of the commotion and a three-dimensional version, with black letters rising vertically from a mound of white sand, mirrors its graphic sensibility. Because the eye chart is repeated so intentionally, the utilitarian typographical form takes on a metaphorical role, a reminder of the limits and subjectivity of vision.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Thai, born Argentina, 1961

Untitled (bicycle shower) 2010, bicycle, water pump, hose, sprinkling can, stand, and bracket

I remember reading about Rirkrit Tiravanija in Art in America in the 90’s. The artist became famous for cooking traditional Thai meals in New York galleries and then sharing them with gallery visitors. These performances were quietly brilliant, a hospitable act of rebellion against the predominant commodity culture. Where other artists talked about creating community while hanging expensive, sellable works on gallery walls, Tiravanija created community through action in the present. The artist’s cooking performances celebrated a unique cultural heritage and shared it with others in an inclusive way. In 1998, Tiravanija and several other artists embarked on a new social experiment near Chiang Mai, Thailand, a community called The Land. The place is a communal farm without electricity or running water, as well as an environment for artistic, environmental, and scientific creativity. It produces enough food to feed its participants, as well as the neighboring villages.

On first glance, Tiravanija’s fully functioning bicycle shower seems out of place in the BMA’s pristine galleries. The contraption was created for utilitarian purposes, to improve the quality of life for residents at “The Land,” and could work effectively for many of the world’s developing nations. Brought into a museum context, Tiravanija’s bicycle is recontextualized and references the ‘Godfather of Readymades’ – Marcel Duchamp, who attached a bicycle wheel on a kitchen stool in 1913 and pronounced it art. From a formal standpoint, you can’t help but examine the disparate elements of the bicycle shower – the bike, hose, and watering can – arranged together simply without alterations, and view them as heightened meta-versions of themselves, symbols of solid universal design.

More importantly, though, the bicycle shower heightens the viewers awareness of the array of creative possibilities available to artists today. There’s something inherently noble about transforming everyday available objects into useful tools and using one’s creative skills and ingenuity for the common good. Taravanija’s egalitarian approach to art making continues to influence generations of young artists, challenging them to create an art practice that nourishes healthy communities and encourages sustainable environmental practices.

The brand-new Contemporary Wing at the BMA is officially opening to the public on Sunday, November 18 from 11-5, featuring performances, workshops, and demonstrations. The museum will host a Late Night party on Saturday, November 17 from 9 pm to midnight to celebrate the momentous occasion.

All events are free to the public. For more information, go to www.artbma.org.

* All Sarah Oppenheimer images by James Ewing