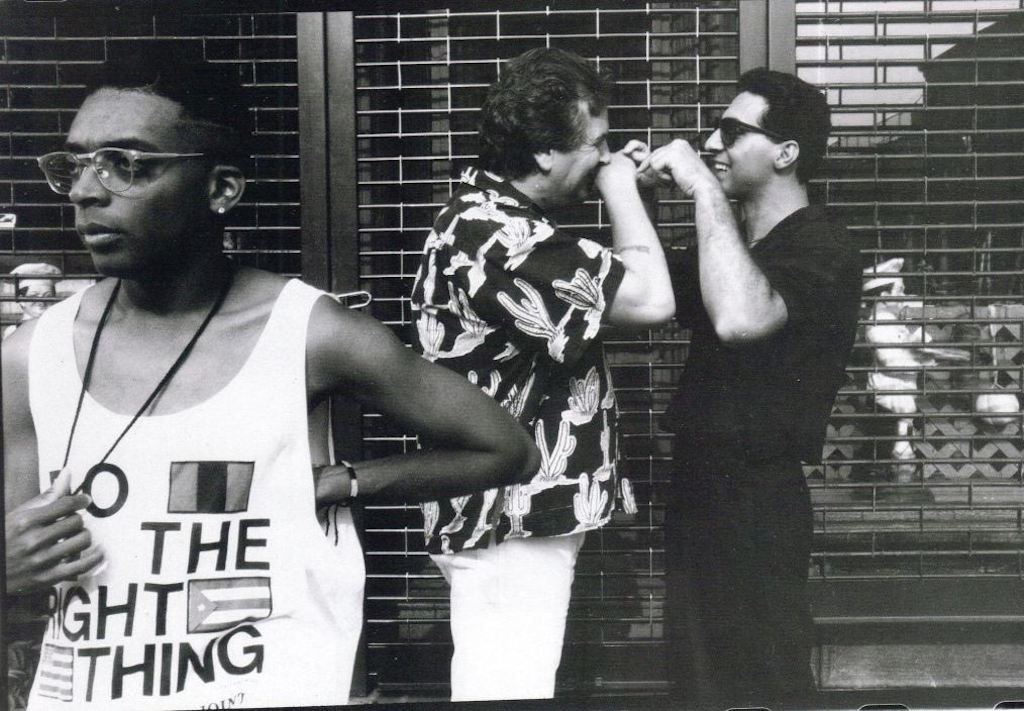

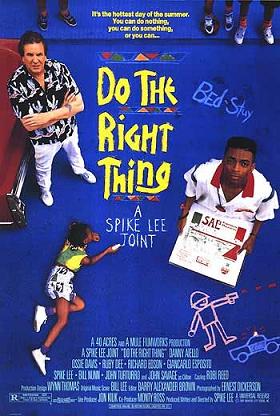

Marking the 25th anniversary of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (which was named a “culturally significant” work by the Library of Congress and earned a place on the American Film Institute’s 2007 list of the 100 greatest American films), the Charles Theater is screening the film three times this week, as a part of its revival series.

Given the recent events in Ferguson, MO, the film – which focuses in part on racial and ethnic tensions in a Brooklyn neighborhood, and includes an act of police brutality – is not merely historically interesting; indeed, it’s pressingly relevant. But what to make of Do the Right Thing, in the summer of 2014? Following the initial showing at the Charles, Kerr Houston offers some thoughts on the matter.

So much has changed since then. When Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing was first released in June of 1989, the Berlin Wall still stood intact, Nelson Mandela was in prison, a federal law banned all travelers with HIV from entering the U.S., and a 27-year-old named Barack Obama had recently completed his first year of law school. Fine Young Cannibals were sitting atop the Nielsen charts, Michael Jordan had yet to win an NBA title, and Tim Berners-Lee was drafting a proposal for a hypertext project that would yield, about a year later, the first web page.

But so much, too, remains the same. A Disney film about a princess exiled from her palace – Ariel, or Elsa – still grosses tens of millions of dollars, scandals still plague American governmental agencies (HUD, the Pentagon, and now Veterans Affairs), and tensions in the Middle East remain high. And outlandish violence is still perpetrated upon the bodies of young African-American men. In recent weeks, the name of Michael Brown has dominated the news cycles; in the summer of 1989, it was Yusef Hawkins – and, too, Radio Raheem, who was at the center of Lee’s incendiary tale of sudden violence in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

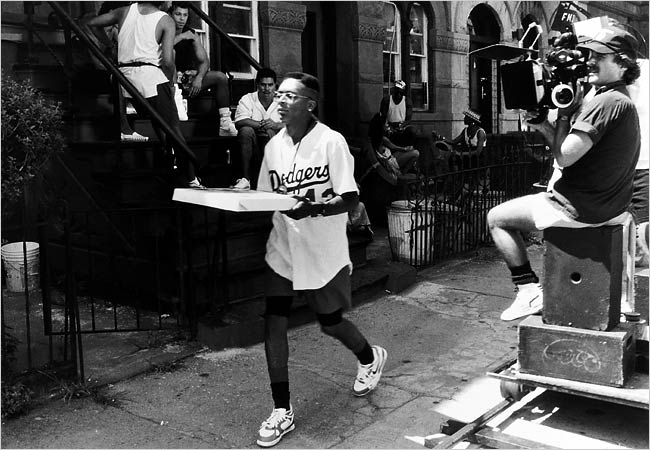

So what can we make of Do the Right Thing in 2014? Certainly, as a piece of art, it still holds together. Wynn Thomas’ designs still evoke the edgy discomfort of a blazing Brooklyn summer day, and Ernest Dickerson’s cinematography remains effectively jittery, its rapid cuts and slanted angles heightening the sense of tension on the block. Lee is still complicatedly appealing as Mookie, the gangly pizza delivery boy who ably navigates a complex ethnic landscape but also functions as an agent of harsh, impromptu justice. And the many memorable bit characters, from Mother Sister to Mister Señor Love Daddy, still stand as a testament to the imaginative force of Lee, who penned the script in two weeks of fervent activity in 1988.

But it may be the timing of the film’s rescreening that is most affecting. At the very least, it’s eerily unsettling. Just about a month after an unarmed Eric Garner was killed by a New York City police officer using a choke hold, NYPD officers Ponte and Long will subdue Radio Raheem with a choke hold that Bill Nunn, who played Raheem, would later claim “was as close to real as you want to get.” And, just a few days after crowds looted Mumtaz Lalani’s Dellwood Market in Ferguson, Missouri in an aggrieved response to the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by Officer Darren Wilson, an angry host of protestors will assemble on the big screen at the Charles and will exact a vengeance on Sal’s Pizzaria. Art will imitate reality – which, in turn, echoes an artwork.

But how, then, to break this tiring cyclicality? How might we work to ensure that we won’t be exiting the Charles Theater in 2039 and exclaiming all over again on the continued relevance of Do the Right Thing?

There are no easy answers, of course, to such a question. But it does seem fair to note that both the film and the protestors in Ferguson articulate a basic lack of faith in the very systems that are meant to effect and protect our citizenry. Most obviously, this means the police, the theoretical defenders of public safety. In a recent piece written in response to the events in Ferguson, Ta-Nehisi Coates bluntly argued that “Among the many relevant facts for any African-American negotiating their relationship with the police the following stands out: The police departments of America are endowed by the state with dominion over your body.”

Certainly, the corpses of both Radio Raheem and Michael Brown offer evidence in support of such a dark view. But aren’t such egregious acts of violence then punished in the justice system? Not necessarily: rather, one of most consistent themes discernible in local blacks’ reactions to Michael Brown’s killing is a flat distrust in the mechanisms of justice. The trial of George Zimmerman, after all, ended in an acquittal; so, too, did the trial of one of the two defendants tried for the shooting of Yusef Hawkins. The very institutions entrusted with the maintenance of our safety seem unable to consistently act dispassionately and fairly.

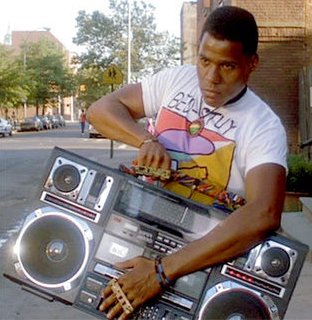

Indeed, they sometimes also seem incapable of even imagining a world that is not riven by racial and ethnic difference – a tendency that has led in turn to a public suspicion of governmental or official mechanisms of representation. I’m thinking, for example, of the cynical release, last week, of surveillance camera images of Brown allegedly robbing a convenience store. As John Timpane noted in the Philadelphia Inquirer, the release of those images formed part of a much larger struggle to define the black male body. That struggle, in turn, is an ancient one – and it’s also at the heart of Do the Right Thing, where it’s accomplished in large part through exclusion. Think, for instance, of Public Enemy’s claim, in the movie’s recurrent anthem, that “Elvis was a hero to most / But he never meant shit to me, you see… / Most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps.” Or, we might add, on the Wall of Fame in Sal’s Pizzeria, which is devoted (to the great frustration of Buggin’ Out) completely to photographs of Italian-Americans. The images proffered by the powers that be, in short, are shot through with ideological bias.

Okay, then – but, still, what to do? At the very least, it seems clear that what we can’t do is merely preach a return to order. After all, as Steven Thrasher remarked in The Guardian, “Too often, a call for non-violence becomes a blanket excuse to do nothing and maintain the status quo.” And that status quo is, pretty clearly, not entirely worth defending. How, then, to fight the power? What is the right thing that we’re enjoined to do?

For some observers of Do the Right Thing, we face a rather clear choice: we can respond with violence or with passive resistance. That, at least, was the conclusion of Jerome Christensen, in a 1991 essay in Critical Inquiry. Lee’s film, contended Christensen, relies upon a set of bald dichotomies or Manichean contrasts: black and white, love and hate, friend and enemy. And so, for Christensen, the film’s closing shot of a black-and-white photograph of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X acts as a concise summary of a binary political worldview. You might think, for a contemporary analogy, of contrasting approaches to the AIDS crisis: where ACT UP advocated a strident, confrontational advocacy, artists such as Felix Gonzalez-Torres relied instead upon a gently elegiac visual poetry. A battle in the streets, then, or an oblique abstraction: the two represent entirely divergent approaches.

But in fact those were never the only options open to those who sought change. Indeed, as W.J.T. Mitchell remarked, in a rejoinder to Christensen’s essay, Lee’s film actually seeks to dissolve stark binaries. It does this, for instance, by depicting a wide range of reactions to racial violence: from the quiet, cowed dissent of the old men on the curb to the boycott organized by Buggin’ Out, and from the blaring pride of Radio Raheem to Mookie’s climatic act of violence, the film sketches a range of possible acts of political resistance. Thus, too, the film echoes reality: for in fact the actions of the African National Congress or the Black Panthers or the protestors in Ferguson have never been simply binary. They are, of course, diverse, and debated. Coates demands reparations, to begin to repair the legacy of slavery; Rev. Jesse Jackson argues instead for higher-paying local employment opportunities. Opposing an unjust system can take many forms.

But let’s listen more closely, for a moment, to Buggin’ Out asking Sal why there are no brothers (rather than blacks) on the Wall of Fame. As Mitchell has pointed out, his question isn’t rooted, it seems, in racial essentialism; rather, it’s based on what Mitchell calls a fraternal principle, or a sense that we have more in common than racial epithets and walls of fame imply. You can discern this principle, too, in the Korean grocer’s assertion to a largely black crowd that “I black… You me, same.” It’s a funny line, but its place in the film also suggests that Lee sympathizes with its essential logic. Indeed, that logic is then qualified in the rap that emanates from Radio Raheem’s boom box: “People, people we are the same / No, we’re not the same / Cause we don’t know the game.” The lack of jobs, or the absence of fair loans, or the legacy of slavery, or… well, whatever your view, such structural inequities may keep us apart. But, despite such gulfs, might we discover some common ground?

Do the Right Thing suggests that we might. And it even begins to suggest how we might. I have in mind here the film’s repeated reliance on characters speaking directly into the camera. These dissolutions can be violent: in one challenging montage, characters hurl racial slurs at us. They can also be jarring; after all, Lee’s approach was informed by Brecht’s epic theater and its interest in forcing passive spectators to acknowledge their own place in relation to the acted fiction. But they can also be humanizing; they create, after all, a dialogue, a face-to-face. Or, in the logic of the film, they represent an alternative to the icy, objectifying racism of Officer Ponte, who mouths the words “What a waste” as his squad car drives by Sweet Dick Willie, Coconut Sid, and ML. Lee’s reliance, elsewhere, on the returned gaze invokes instead the ennobling philosophy of Martin Buber. Or, as Margaret Olin has put it, “If you can look back, you cannot be possessed by the gaze of the other. What is proposed is not a staredown. It is shared gaze.”

Does this really mean anything, in the harder light of the real world? To be sure, it would be hard to argue that Lee’s film did much to solve the endemic problem of endemic racial violence. Similarly, the airy pronouncements of the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas (that the face imparts a command: Thou shalt not kill) feel almost naïve in the wake of the deaths of Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, and Michael Brown. But wait: think of the showdown in Ferguson this past Tuesday, when a police officer carrying a raised rifle pointed at a crowd said, “I’m going to fucking kill you! Get back, get back.” A video captures the next few seconds:

Voice in crowd: You’re going to kill him.

Officer: Get back!

Voice: What’s your name?

Officer: Go fuck yourself!

Voice in crowd: Your name’s ‘Go Fuck Yourself”? All right, Go Fuck Yourself.

Admittedly, it’s hardly the most humanizing dialogue. But as Amy Davidson of The New Yorker has pointed out, the scene then resolves itself: the edgy cop (who has since been suspended) is led away. We’ll never know, of course, if the rather witty and undeniably inclusive attempts at conversation on the part of an anonymous member of the crowd had any effect on the cop’s decision not to pull the trigger. But it does seem clear that they created an air of dialogue, rather than unidirectional threat.

And dialogue, it’s worth repeating, is powerful – which is why Lee is far from the only artist to invoke its force. Think, here, of Thomas Hirschhorn’s Gramsci Monument, a ramshackle series of structures (including, like Lee’s set, a radio station) erected in a housing project in the South Bronx last year. Part community center, part lecture hall, the project involved a number of residents, but it also foregrounded the issue of fraternal dialogue. “I appreciate you, man,” Erik Farmer, the local tenants association president, told Hirschhorn, “Thanks a lot. We bump heads all the time, but that’s my brother.” Or think of Marina Abramovic’s remarkable 2010 piece “The Artist is Present,” in which she sat across a table from a chair that held a rotating cast of riveted spectators – many of whom broke into tears, overwhelmed by the simple fact of mutual presence.

Finally, it’s worth turning to a recently produced video that documents the return of Lee, Danny Aiello, and Wynn Thomas to the block in Bed-Stuy where they shot Do the Right Thing. The block is different now, in some ways; it’s been largely gentrified, and Sal’s Pizzaria is a parking lot. But a number of the structures in the film still stand, and it’s touching to see Lee remark with an almost childish enthusiasm on certain stoops and window sills. Perhaps most affecting, though, is the lively back-and-forth between Lee and Aiello. In Do the Right Thing, of course, the two were far from aligned; Sal was Mookie’s employer, and one of the final scenes in the film centers on the bitter distance between them. But in 2014, the two men come together and simply reminisce – and they do so, wonderfully, like brothers, interrupting each other, quibbling about details, finishing each other’s sentences, and laughing raucously at one another (see, especially, the 10:55 mark of the video). They speak, in short, like equals: equals amazed at the limits of their memory and, simultaneously, at the legacy of the film that they helped to create.

So much has changed since 1989. And yet, so much remains in place: 25 years on, we are still surrounded by fallible institutions, myriad suspicions, and coarse stereotypes. Consequently, it can seem ridiculous to think that we can work to change such intractable forces. But perhaps, in such a context, simply seeing each other as human can constitute, in its own right, a radical and valuable act.

*Do the Right Thing will be shown at The Charles on Monday, August 25 at 7 p.m., and Thursday, August 28 at 9 p.m.

Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.